By

Hank Reineke

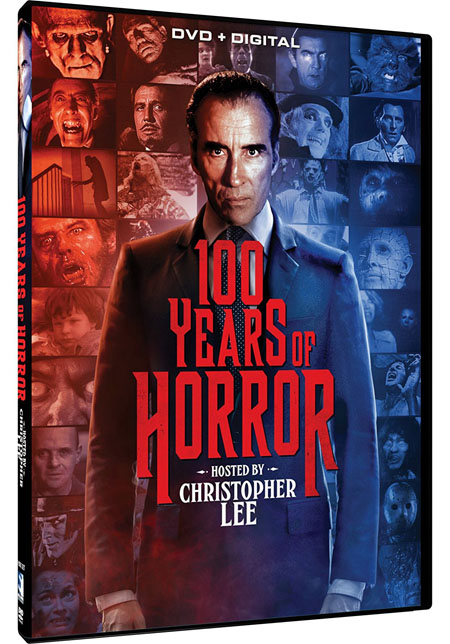

The first thing you note when reading the sleeve notes

for 100 Years of Horror (Mill Creek Entertainment)

is the three-disc set’s staggering running time: ten hours and fifty-five

minutes. It’s a somewhat daunting task

to review such a monumentally staged effort as this, one at least partially

conceived as a labor-of-love. The series

makes a noble effort to trace the history and the development of the horror

film from the silent era through the slasher films of the 1980s and a bit

beyond, not always neatly or logically compartmentalizing sub-genres as

“Dinosaurs,†“Aliens†“Gore,†“Mutants,†Scream Queens†etc. along the way. It’s a bit difficult to precisely date when host

and horror film icon Christopher Lee’s commentaries and introductory segments

were filmed. The set itself carries a

1996 copyright, but Lee makes an off-hand mention of the “new†Dracula film

starring Gary Oldman… which would date the saturnine actor’s participation to

1992 or thereabouts. Later in the set,

Lee references Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein,

which then confusingly forward dates the documentary to 1994.

It’s also unclear where this series was originally

destined. With its twenty-five minute

running time per episode, it would appear as if this twenty-six part series was

produced with the intent of television distribution in mind. 100

Years of Horror is one of the earliest efforts of executive producer Dante

J. Pugliese who would carve out a career producing a number of these minimal

investment “clip show†style documentaries. This series first appeared as a 5 volume VHS set via Passport

International in the latter days of 1995, and has since enjoyed several DVD

releases; there were both cut-down versions and a

highly-sought-after-by-collectors box set issued in 2006. This new issue by Mill Creek not only brings

the set back into print with new packaging, but does so at a very reasonable

price point: MSRP: $14.98, and even

cheaper from the usual assortment of on-line merchants.

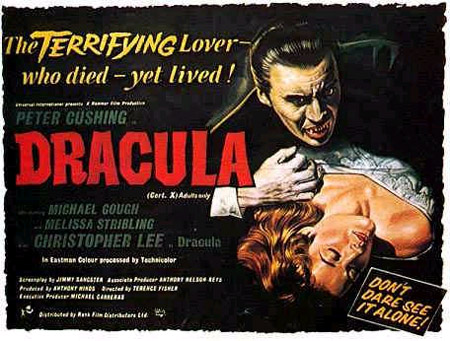

Perhaps acknowledging Christopher Lee’s contribution to

the legacy, the series first episode is fittingly dedicated to Dracula and his Disciples. Lee was, inarguably, one of the two most

iconic figures to essay the role of Count Dracula. Though Bela Lugosi’s halting speaking manner,

grey pallor and widow-peaked hairline remains the more iconic visual portraiture,

Lugosi actually only portrayed Count Dracula in a feature-length film twice: in

the 1931 original and, for the final time, in Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948). Lee, on the other hand, shot no less than seven

Dracula films for Hammer Studios and one for Jess Franco. Though he would log considerably more

cinematic hours on screen as the Prince of Darkness, the gentlemanly Lee

generously allows here that even some forty years following the actor’s death

in 1956, Bela Lugosi was still “inexorably linked†to the public’s persona of

Dracula.

Though he would never work with the actor – as he would on

two occasions with Lugosi’s occasional foil Boris Karloff - Lee recalled his first

attendance at a horror film in a cinema was Lugosi’s Dark Eyes of London (1939). Lugosi would, in some manner of speaking, unwittingly pave the way for

Lee’s future assumption in other similarly cloaked roles. As had his predecessor,

Lee would portray several other vampire characters on film that were Count Dracula

in all but name. Just as Lugosi would exploit

his image as Transylvania’s most famous resident in such films as Return of the Vampire and Mark of the Vampire, so would a fanged

Christopher Lee with such impersonations as Dracula

and Son and Uncle Was a Vampire.

The documentary makes clear that, no matter how celebrated

either man’s portrayal was, neither actor held dominion on the character. The film points out that several other actors

- Francis Lederer and Lon Chaney Jr. among them – have tackled the role to reasonable

degrees of satisfaction. It was also

pleasing to see a brief interview segment with one of my favorite Dracula’s,

the wizened John Carradine, captured in his eighties here. Carradine triumphantly recounts not only did

he appear as Dracula in “three†films for Universal (well, three, if you choose

to count his appearance on a 1977 episode of NBC-TV’s McCloud (“McCloud Meets Draculaâ€). Carradine was also mysteriously prideful of his appearing as a Count

Dracula-style character in several obscure films shot in Mexico (Las Vampiras) and the Philippines (the

outrageous and exploitative Vampire

Hookers). What the Mexican and

Filipino efforts might lack in comprehensibility and budget, they’re nonetheless

not-to-be-missed totems of low-brow Midnight Movie Madness. For whatever reason, Carradine made no

mention of his top-hatted participation the wild and wooly William (“One Shotâ€)

Beaudine western Billy the Kid vs.

Dracula (1966), a long-time “guilty pleasure†of mine.

Many of the featured players of the Universal Studios era

of the Golden Age of Horror were gone by the 1960s and 1970s, so many of the on-camera

reminiscences from this era are left to be re-conjured by surviving family

members. Hoping to put a rest to the

rumors that his father was not on good terms with Boris Karloff, Bela Lugosi

Jr. contends any suggestions of a rivalry between the two were professional and

not personal. As early as the mid-1930s Karloff

was getting the better paying and more interesting roles. Bela was often toiling

in a series of mystery-horrors for such cheapie studios as Monogram. The younger Lugosi admits his father had paid

dearly for passing on the opportunity of portraying the monster in the first

Universal Frankenstein film of

1931. As the script called for the

monster to be mute throughout the feature, the prideful Lugosi thought his

acceptance of the role would be a “misuse of his talent.†He would later regret his decision, as it was

one that would seal his fate - during the course of his working life, at the

very least - as a second-tier boogeyman to “Karloff the Uncanny.†The role of the Monster was eventually

consigned to Karloff, whose masterful performance in both the original and two

sequels (Bride of Frankenstein and Son of Frankenstein) made the sinister Englishman

a bona fide worldwide star.

As might be expected with any documentary series of ambitious

scope, there is a bit of accommodation made for the sake of inclusivity. The episode celebrating the cinematic legacy

of Robert Louis Stevenson’s “The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde†(first

published 1886), is presented somewhat chronologically with mentions of various

rare silent shorts and a deeper look at John Barrymore’s more famous silent

version of 1920. The most celebrated

version is the 1931 Paramount version with Fredric March, a film shot very much

in the tradition of the two recent Universal features, but for which March received

an Academy Award – the first such honor to be bestowed upon a Hollywood horror

film.

It’s also here that the filmmakers tenuously stretch the

definition of films encapsulating a Jekyll/Hyde formula. They suggest such films as diverse as

Universal’s Black Friday, Monogram’s The Mad Monster, The Hideous Sun Demon, and Jerry Lewis’ The Nutty Professor - amongst others - are kindred spirits. While I concede these tales are allegorical

to the original Stevenson novel, they’re original works in their own

right. Let’s face it; a monster movie

without a mad scientist lurking about and causing mayhem is hardly worth

watching. The most fun moments of the Jekyll

and Hyde episode belong exclusively to the Brits. The first features the beautiful Martine

Beswick complaining that producers at Hammer Films were continually pushing her

to bare more of the bountiful gift that was her body than had been mutually

agreed upon when signed on for Dr. Jekyll

and Sister Hyde. Christopher Lee

took the producers at Amicus to task for their retention of every original name

of every major and minor Stevenson character in their feature I, Monster. That is, of course, for

Lee’s principal character, whose name was changed from Jekyll and Hyde to

Marlowe and Blake for no apparent reason.

There are, very welcomingly, interviews with a lot of old

hands from Hammer Studios. As one might

expect, this set’s segment celebrating the legacy of Baron Frankenstein was

largely dedicated to the memory of Peter Cushing. The skeletal and genial actor would famously appear

as the maniacal and obsessed Baron in six of the seven Frankenstein features

produced by Hammer 1957-1973. Lee offers

that his very old and dear friend and colleague brought a “decadent eleganceâ€

to the role, suggesting that, to three generations of cinemagoers, Cushing was

the one and only Baron Frankenstein. Thanks to the advent of home video, I’m sure that yet another generation

or two can be added to that total… there was, simply, no one better in that

role. The filmmakers also point out that

beginning in the 1950’s, stateside independent producers would “Americanizeâ€

the Frankenstein film legacy for the teen market. Though Dr. Frankenstein were originally of

European descent – a Baron, no less - A.I.P, Embassy Pictures and many other

low-budget programmers chose to bring such “Made in America†creations to the

screens of drive-ins across the U.S.A. Who wouldn’t want to catch a midnight movie with a crass title like I Was a Teenage Frankenstein, How To Make a Monster, or Jesse James Meets Frankenstein’s Daughter?

Though Christopher Lee’s introductions and occasional

appearances throughout tie the narrative line together, each episode is

stitched together with brief interviews of film technicians and actors,

excerpts from still photographs and no shortage of scenes excised from free-use

trailers. If a particular film is

particularly old or has fallen into public domain status, there’s a good chance

we will be treated to an extended showcase of moments from that film. Sadly, these extended segments of public

domain films – most very familiar to obsessive fans - tend to drag down the

pace of several episodes; you get the uneasy feeling they’re mostly included to

pad the running time and allow the writers a lengthy lunch break. Having said this, should you choose to go forage

a snack from the kitchen during one such extended interlude, you do so at your

own peril. There’s a very good chance

you might miss a brilliantly inserted snippet of celebrity gossip or a backstage

technician’s erudite observation.

Much to the filmmaker’s credit, there’s nary a then-surviving

member of the horror film fraternity who doesn’t offer commentary throughout

the set. You can check out this film’s

IMDB extensive cast list to see who is on hand here to share a memory or two,

no matter how brief. These interviews,

to me, are the most illuminating part of the set. As mentioned earlier, Karloff

and Lugosi (and Chaney, Atwill, Zucco et. al.) were already long gone and

unable to contribute, but remembrances of the “Golden Age†are shared by such

veterans as Turhan Bey, Peggy Moran and Nina Foch. In the case of Karloff’s biography, the team

behind the documentary’s production has made good use of snippets of vintage television

footage sourced from such programs as the Carol

Burnett Show, Route 66, Thriller, and This Is Your Life. Footage

excerpted from Lugosi’s semi-famous shipboard interview of December 1951 is

also used, as is a scene from Hollywood

On Parade where Bela puts the bite on American sweetheart, Betty Boop.

Originally, and perhaps more sensibly, conceived as a documentary

of two hours, a decision was made along the line to expand the material sale to

the British television market. While new

and old fans will surely be schooled in many facets of classic horror lore, it

must be said some episodes are better researched and written than others that serve

mostly as nothing but clip shows. The

series definitely benefits when writer-producer-horror historian Ted Newsom

jumps aboard and helps more knowledgeably guide the ship. It is a pity that the set has not been afforded

an HD transfer to Blu. After a few

episodes I had to abandon watching these documentaries on the 56†set in the

living room – image quality varies wildly from acceptable to mildly blurry to near

headache-inducing. The set appears

slightly less compromised on the 27†small format flat screen in the

bedroom. I also found the set not terribly

conducive to binge-watching. There are

several re-uses of Lee’s voice-over commentaries and plenty of double and

triple dips of familiar trailer and archival footage… the repetition does get

tiring after a bit. I’d suggest playing

an episode or two of 100 Years of Horror

as a prelude before settling down for your Saturday night monster movie.

(The DVD set includes a digital download version.)

CLICK HERE TO ORDER FROM AMAZON