EVE GOLDBERG presents an in-depth examination of the only film Marlon Brando ever directed: "One-Eyed Jacks" (1961)

"ONE-EYED JACKS: AMERICA AT THE CROSSROADS"

A new movie schedule arrived

every few months. A two-sided paper

treasure chest brimming over with promises of time travel, existential wisdom,

and singing in the rain. Wild

Strawberries, City Lights, Battle of Algiers, Belle de Jour.

We grabbed up the schedule

and studied it with care, taped it to the refrigerator door, marked our

calendars. The African Queen, Yojimbo,

Rules of the Game.

We made cinema voyages all

over town — to the Vista in Hollywood, the Nuart in West LA, the art deco Fox

Venice. Before VCRs, DVDs or streaming,

revival movie theaters were about the only place a film junkie could get a

fix. We might find an occasional nugget

on late night TV, John Ford’s Stagecoach,

perhaps, or Invasion of the Body

Snatchers, but for the most part, it was the revival house or nowhere. Citizen

Kane, La Dolce Vita, Alphaville.

There was rumor of a weird

Western called One-Eyed Jacks,

starring and directed by Marlon Brando. Nobody we knew had seen it. The

movie took on the aura of myth. Was there really a scene where Brando gets

whipped? What had the famously

iconoclastic actor done with the time-worn clichés of the horse opera?

Finally, I think it was

1974, One-Eyed Jacks arrived. We trooped down to the Fox Venice, waited in

a long line, found seats in the filled-to-capacity theatre, and settled in for

the ride. We were not disappointed. From the opening shot — Brando casually

eating a banana during a bank robbery — the film was like no Western we had

ever seen. Moody, psychological,

ambiguous, it was awash in sadomasochism, with a brooding Brando in nearly

every scene. And yes, the actor gets his

whipping in a scene of perverse cruelty which sears into memory.

Back in 1974, we knew we had

seen an odd, strangely subversive, one-of-a-kind film. We didn’t know, however, that this quirky

little revenge gem would someday be considered an important (if flawed)

masterpiece of cinema, and a fascinating link between two eras in Hollywood…and

America.

The Western is a

quintessentially American film genre. From its earliest days, the cowboy drama was about good guys (white

lawmen) confronting bad (Indians, outlaws). Each movie was a tale of expansionist dreams and masculine

aggression. Each was a saga of

civilization triumphing over savagery. The Western was, to quote film critic J. Hoberman, “the way America used

to explain itself to itself.â€

Edwin Porter’s 1903 film, The Great Train Robbery, was one of the

first Westerns. This 12-minute story in

which bandits rob a train, only to be pursued by a posse of lawmen,

revolutionized the art of cinema. Porter

used ground-breaking techniques such as cross-cutting and close-ups to create a

suspenseful, compelling narrative. The

basic elements of the genre were set.

The Western remains

instantly recognizable across more than a century of evolving media and

myth-making. Gunfights, holdups, and

massacres. Horses, trains, rustlers, and

barroom brawls. School-teachers,

stampedes, and six-shooters.

The Golden Age of the

Western is often considered to be the years 1946-1973. Following World War II, with the Cold War

blazing hot on the beaches of Korea, the U.S. declared itself the new global

sheriff in town. At home, the Eisenhower

Era earned a reputation as being a time of complacency and consumerism. But these were also the McCarthy years, when

right-wing witch hunts against political progressives were ruining lives and

careers. And, at the same time, the seeds

of change were taking root. A young

civil rights movement began asking America: What the hell are the good guys who

fought Hitler doing about racial discrimination and bigotry at home?

In this landscape, mature

conventional Westerns like My Darling

Clementine (1946), Shane (1953),

and Rio Bravo (1959) stood shoulder

to shoulder with a new type of movie. Westerns such as Broken Arrow (1950), High Noon (1952), and Johnny

Guitar (1954) tweaked, twisted, and updated the genre — Broken Arrow with a sympathetic

portrayal of Native Americans; Johnny

Guitar with an arch Joan Crawford at the center of a sexually ambiguous

melodrama; High Noon as a parable of

the anti-communist witch hunts which were plaguing America (and Hollywood) at

that time.

Two landmark Supreme Court

decisions opened the way for these unorthodox films to be made. In 1948, the Court ordered the Hollywood

studios who owned theater chains —MGM, Paramount, 20th Century Fox,

Warner Brothers, and RKO — to divest themselves of those theaters. The idea was that a studio’s control over

production, distribution, and exhibition represented restraint of trade. In 1952, citing the First Amendment’s freedom

of speech clause, the Court eliminated government censorship from movies. Until that ruling, there had been hundreds of

state and local “decency†ordinances that the film industry felt compelled to

follow. Now, less fettered by censorship

(Hollywood still had to deal with pressure from conservative religious groups),

filmmakers were freer to produce unconventional fare. Untethered from studio demands, exhibitors

were free to book a wider range of movies.

The movie studios were also

facing stiff competition from the new medium of television. I Love Lucy, Gunsmoke, and Leave It To

Beaver were pulling eyeballs (and revenue) away from the cinema. Movies sought to differentiate themselves

from their small screen cousins. One way

was to GO BIG. Wide-screen, Technicolor,

3-D, stereo. Another was to go

off-beat. Influenced by the edgy,

innovative films coming out of Europe, a slice of American movies began to

shade darker, bleaker. They began to

challenge mainstream values.

And into this mix of

cultural and economic change stepped the brightest star in the Hollywood

galaxy.

Marlon Brando’s 1947 tour de

force performance as Stanley Kowalski in the Broadway production of Streetcar Named Desire revolutionized

the art of acting. His performance in

the film version of Streetcar made

him an international movie star and sex symbol. In The Wild One, Brando transformed himself into an alienated,

leather-jacketed biker — and became the poster boy of rebellious youth. In 1954, he won his first Oscar for his

portrayal of a deeply conflicted, tough-but-vulnerable, dockworker who rats out

a corrupt union boss in On the Waterfront.

By age 31, Marlon Brando was

the most popular movie star in the world. He was a bigger box office draw than Cary Grant, John Wayne or Jimmy

Stewart, all of whom were beginning the downside of their careers. His contemporaries, James Dean and Montgomery

Clift, were either dead (Dean, at age 24 in a car crash) or in steep decline

(Clift in a drug and alcohol haze).

But Brando wanted to do more

than act.

It was exactly at this time

that the Hollywood studios were losing their grip on the film industry. Without their own theaters, the studios were

no longer motivated to churn out copious amounts of product each week to fill

seats. Add to that, movies were losing

audience share to television. So the

studios began cutting back on the number of films they released each year. With less product in the pipeline, they were

choosing not to renew hefty, long-term contracts with their top players. Movie stars including Burt Lancaster, Cary

Grant, and Kirk Douglass used this opening to form their own production companies.

Brando named his company

Pennebaker Inc. in honor of his late mother (Pennebaker was her maiden

name). He said that the purpose of his

new venture was, “to make pictures that were not only entertaining but had

social value and gave me a sense that I was helping to improve the condition of

the world.â€

The big studios still

provided the sound stages, technicians, know-how, and big bucks for smaller

companies. Pennebaker partnered with

Paramount, setting up shop on their Melrose Avenue lot. Pennebaker’s first film was Sayonara, the story of an American ace

fighter pilot (Brando) who falls in love with a Japanese actress. The movie dealt with issues of racism and

bigotry. It was a critical success.

Brando was particularly

interested in making a Western. For

several years, he looked for properties to adapt, and worked on developing a

script set in the Old West. At one

point, he even attempted to adapt The

Count of Monte Cristo to the Old West. But nothing seemed to jell. Then he caught wind of a novel, The Authentic Death of Hendry Jones,

based loosely on the Pat Garrett/Billy the Kid legend. The book had already been optioned by

producer Frank Rosenberg, and a screen adaptation written by Rod “Twilight Zone†Serling. Serling’s script was being revised by a bit

actor with aspirations to write and direct — Sam Peckinpah. Brando brought the book, screenplay,

producer, and writer over to Pennebaker. He worked with Peckinpah on the script for a while. Eventually, he replaced Peckinpah with novelist/screenwriter

Calder Willingham, who in turn was replaced by veteran screenwriter Guy

Trosper.

To direct, Brando hired

maverick filmmaker Stanley Kubrick, fresh off his anti-war film Paths of Glory. However, after working together for six

months, Brando and Kubrick couldn’t agree on a final script. So they agreed to part ways. Brando decided to direct the movie himself.

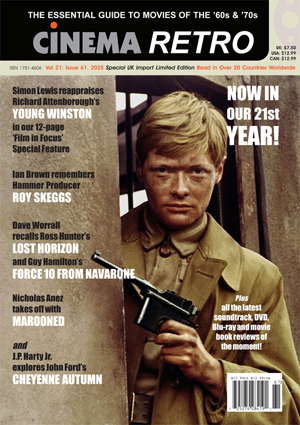

For the cast of One-Eyed Jacks, Brando assembled a group

of supremely talented character actors, including Katy Jurado, Ben Johnson, and

Slim Pickens. He chose his close friend

and fellow Method actor, Karl Malden, to co-star. Shooting began in 1958, in Monterey,

California. Along with his acting and

directing duties, Brando worked daily with screenwriter Trosper, revising the script. “I was making it up as I went along…I didn’t

know what I was doing,†the first-time director readily admitted.

Interested in bringing

emotional and psychological depth to his Western, as well as a feeling of

spontaneity, Brando encouraged his cast to improvise their lines. Numerous takes were shot, each a bit

different, until the director got what he was looking for. Conscious of his directorial inexperience,

Brando also made sure to cover each scene from numerous angles, shooting more

than most directors would, to be sure he had what he needed for editing.

Understandably, Brando cared

deeply about this movie; he wanted everything to be just right. On location in Monterey, with a large cast

and crew on payroll, he waited for just the right light, just the right wave,

before shooting a scene. All this took

time. Shooting ran over-schedule. The budget began to balloon. Paramount executives, who were funding the

film, began to get nervous.

Next, filming moved onto the

Paramount lot, where elaborate sets such as the “fiesta scene†had been

built. In the controlled environment of

a Hollywood studio, things were expected to go more smoothly. But no such luck. In a freak Los Angeles storm, the One-Eyed Jack sets were destroyed.

Final filming took place in

Death Valley, California, where temperatures hit 117°. In addition to this extreme heat, the

production team had to deal with their lead actor’s obvious weight gain. Brando had steadily put on pounds during the

course of production. His costumes

needed to be adjusted and re-sewn — again and again. Camera angles were arranged to mask his

expanding girth.

By the time shooting was

complete, One-Eyed Jacks’s three

month shooting schedule had stretched to six.

After months of painstaking

editing, Brando finally screened his cut for Paramount. The movie was eight hours long. Paramount insisted that he drastically

shorten the film. They also demanded

re-shoots, including a new “happier†ending. Brando and his editor began re-cutting. The production team was re-assembled and the requisite new scenes were

shot. When Brando showed the studio his condensed

cut, it was five and a half hours long. At this point, Paramount took over the editing process. Brando walked away from his movie in frustration

and disgust. He would never approve the

final cut.

By the time it was complete, One-Eyed Jacks’s $1.8 million dollar

budget had swollen to $6 million. Today,

many would agree that the 141 minutes that made it to the screen was worth

every penny.

Shot in sumptuous,

wide-screen VistaVision, with elaborate set pieces and studio-created costumes,

One-Eyed Jacks has the look and feel

of an old fashioned Hollywood Western. Plot-wise, it is a classic revenge story. The movie begins with Rio (Brando) and his

partner, “Dad†Longworth, robbing a bank in Mexico. Longworth betrays Rio and takes off with the

loot, leaving Rio to rot in a Mexican prison for five years. After he escapes, Rio tracks down Longworth

who is now a prosperous sheriff in a small California town, He finds Longworth ensconced in a comfortable

home with a Mexican-American wife and a grown step-daughter, Luisa. Thirsting for revenge, Rio plots with new

outlaw partners to rob the town bank right under Longworth’s nose. For further revenge, he seduces the sweet and

innocent Luisa.

Longworth seethes when he

discovers that his former friend has seduced his step-daughter. He captures Rio and personally administers a

vicious public whipping. Then he crushes

Rio’s gun hand. Rio and his gang retreat

to a nearby fishing village where Rio recuperates and plans his next move. Without Rio’s approval, the gang robs the

bank. The robbery turns into a shoot-out

and a girl is accidentally killed. Using

the killing as a pretext (even though Rio was not even present for the

incident), Longworth puts Rio in jail to await his execution by hanging. Luisa,

who has fallen in love with Rio, tries to help him escape, but fails. Eventually, Rio escapes on his own. He kills Longworth in a shoot-out and rides

off with Luisa.

However, within this typical

Western plot, lies a subversive story. From the opening scene where bank robber Rio eats a banana, then

casually tosses the peel onto a gold scale, the film is in rebellion against

the conventions of the genre. For

starters, while early scenes take place in the arid Mexican desert, much of the

later action is set against the crashing surf of the verdant Monterey coast,

assuring that the movie never quite feels like a “normal†Western.

Released in 1961, here’s

what major critics had to say about the movie at that time.

“It proceeds in two

contrasting styles,†wrote New York Times

critic Bosley Crowther. “One is hard

and realistic; the other is romantic and lush. All he way through it runs a jangle of artistic ambivalence.â€

“The bizarre action is set

off by the classic Hollywood iconography of the western landscape,†opined Dave

Kehr in the Chicago Reader.

Perhaps, though, it’s less

the actual action which is bizarre, but rather the meaning woven into the action, the psychological and emotional

reverberations that ricochet around each scene, seemingly incongruous amongst

the Old West tropes of gunslingers, outlaws, sagebrush, and horses. Add to that a layer of political subversion

that simmers just below the surface, and it’s no wonder that critics and

audiences didn’t quite know what to make of this strange cinematic stew.

The Original Sin of America

is the enslavement of Africans and the genocide of the Native population. Slavery and slaughter were the bedrock of the

new nation’s wealth. One-Eyed Jacks works as a subtle

indictment of white supremacy, patriarchy, and imperial conquest, striking at

the core of the American project. Whether this was a deliberate ideological choice, or whether more the

expression of an incipient sensibility — or some of both — we’ll never know.

What we do know is what we

see. And what we see is a revenge plot

which serves as the scaffolding for a complex questioning of values. The Original Sin of One-Eyed Jacks is Dad Longworth’s betrayal of Rio in the mountains

of Mexico. Longworth uses the gold he

pockets during this betrayal to begin his climb to prosperity and power in

California. As sheriff of Monterey, he

rules as a benevolent, blue-eyed, patriarch. At the annual town fiesta, he speaks from a high platform to his people

— a happily diverse crowd of whites and Mexican-Americans. Beside Longworth floats an oversized balloon

painted with the words Fair Play For All. At home with his Mexican wife and

step-daughter, Longworth plays the role of devoted, loving, husband and

father.

Then Rio shows up and

threatens to crack open the whole façade.

While the town folks of

Monterey are aware of Longworth’s outlaw past, they don’t know about his morally

corrupt soul. “You may be a one-eyed

jack around here, but I’ve seen the other side of your face,†Rio says to his

antagonist.

But in truth, there are two

one-eyed jacks in town. Rio, like

Longworth, uses deception to get what he wants. In particular, he exploits and deceives women. At the beginning of the film, he steals a

ring from a woman during the bank robbery, then gives it to the Mexican

senorita he is seducing. “My mother gave

this to me right before she died,†he lies. Later, he uses this same ploy with Luisa, presenting her with a necklace

he just bought off a street vendor and passing it off as his mother’s. “It would be an honor if you’d wear this,†he

oozes with fake sincerity.

Longworth and Rio’s deceits

create parallel emotional blowback. Neither man is at peace with his own behavior. Both turn their unacknowledged shame

outward. Longworth needs to punish and

kill Rio not simply to maintain his standing in the community, but to silence

his guilt for betraying Rio in Mexico. His self-image as a “good guy†demands that he kill all knowledge of his

wrongdoing. “You will do anything,†his

wife confronts him towards the end of the movie, “to hide the memory of what

you did to him,â€

Likewise, “good guys†don’t

hurt women. So, like Longworth, Rio

turns his guilt outward as well. In

denial that his lying and manipulation of women is hurtful and abusive, Rio

seems to draw the line at physical abuse. When he witnesses a man mistreating a women in a bar, he seethes and

eventually comes to her rescue. His

intervention sets off a shootout during which he kills the abuser.

One of the salient tropes of

the Western is the rationalization of violence. The hero is morally licensed to kill as long as his enemy is presented

as hideous enough to warrant annihilation. (Scalp-taking Indians, for example. Or bomb-wielding Arab terrorists.) As a Western hero, Rio is excused for his aggression towards unsavory

characters such as the woman-abusing bar patron or the lecherous deputy

sheriff. These antagonists are portrayed

as worse than Rio —perfect foils for the genre, perfect targets for Rio’s

projected shame.

But unlike the conventional

Western hero, Rio eventually looks inward. In the course of his relationship with Luisa, he grows emotionally. He gains self-knowledge. He realizes that his lies have consequences,

that his actions have hurt Luisa. He

admits to her that “everything I told you last night was lies.†Admitting to his deceit, he is free to

change. After much brooding and hesitation,

he decides to give up his revenge quest to seek a life of possible happiness

with Luisa. Which is where Rio and

Longworth’s psychological trajectories diverge. Longworth never budges from his need to kill his projected inner demons.

In another turn away from

tradition, the main women characters in One-Eyed

Jacks do not conform to the stereotypical Madonna/prostitute split. Both Luisa and her mother, Maria, are women

of “hearth and home.†They are also

sexual outlaws. Both have sex and become

pregnant out of wedlock. And neither is

ashamed of this fact. Maria lies to her

husband in order to protect her daughter’s affair with Rio. When the game is up, she finally tells her

husband the truth. His response — “Is

this the thanks I get for taking you out of the bean fields?†— reveals the

racist underpinnings of his domestic tyranny.

And speaking of racism, as

the movie progresses and lines are drawn, those who align themselves with Rio —

Luisa, Maria, and his loyal friend Modesto — are all people of color. The “bad guys†are all white males, each of

whom is revealed as a bigot of one sort or another. When Rio and his gang retreat to a small

Chinese fishing village so he can rehab his crushed hand, gang member Bob Emory

is cruel and dismissive towards the Chinese villagers. Later, while betraying Rio, Bob sneers that

Modesto is a “greaser†— just before gunning him down.

One-Eyed

Jacks was not the only anti-racist Western of its time. Films such as Devil’s Doorway (1950), The

Searchers (1956), and Two Rode

Together (1961) dealt with issues of racism. Likewise, Brando’s film was hardly the only

psychological Western of its era; the 1950s were a time when psychoanalysis was

big in Hollywood culture. Often noted

for its Oedipal intimations (“Dad†Longworth, anyone?), One-Eyed Jacks joins a crowd of other “Oedipal Westerns†such as Red River (1947), The Man From Laramie (1955), The

Last Sunset (1961).

However, with its vague

coalition of outsiders, its psychological depth, and its impulse to re-write history,

One-Eyed Jacks, astutely presaged the

future of race, gender and counterculture politics.

When the film was released

in 1961, critiques of patriarchal power and racist hegemony were not exactly on

the lips of the general public. To the

contrary, that was the year President Kennedy inaugurated his New

Frontier. Harnessing Old West symbolism

in the pursuit of global domination, the western frontier moved from Kansas to

Indochina. In the slang of war,

C-rations were dubbed John Wayne cookies, danger zones were referred to as

Indian Country, and secret military ops were codenamed Sam Houston and Daniel

Boone.

As the 1960s became The Sixties, a counter narrative

emerged. Young people protesting the war

in Vietnam allied with African Americans, Chicanos, Native Americans, women,

and gays fighting for civil rights. Counterculture youth grew long hair, wore beads and headbands, lived in

communal (tribal) houses. One

underground newspaper was named the

Berkeley Tribe.

One-Eyed

Jacks not only foreshadowed the new social consciousness of the

1960s, it also prefigured the counterculture-ish revisionist Westerns that

followed. Movies such as Little Big Man (1970), McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971), and Blazing Saddles (1974) blatantly flipped

conventions of the genre as they skewered American expansionism, capitalism,

and white supremacy.

Perhaps, given the social

messages layered into One-Eyed Jacks,

it’s no surprise that Marlon Brando became a political activist in the

1960s. He was an early supporter of the

civil rights movement, participating in the 1963 March on Washington alongside

Dr. Martin Luther King. In 1964, he was

arrested while protesting a broken treaty that had promised fishing rights to

Native Americans in the Pacific Northwest. Later in the 1960s, Brando became a supporter of the Black

Panthers. Most famously, in 1973, he

declined the Academy Award for Best Actor in The Godfather. In his place,

he sent to the stage Native American actress Sacheen Littlefeather who read a speech

about the poor treatment of Native Americans in the film industry. Brando remained a supporter of activist

causes for the rest of his life.

The ending of One Eye Jacks is emblematic of its spot

in film history — one foot in old Hollywood, one foot in a new kind of

cinema. At the conclusion of the movie,

Rio shoots Longworth in a final gun fight. As scripted and originally filmed, Rio and Luisa begin their escape on

horseback, but a dying Longworth gets off one final shot, accidentally killing

Luisa. Paramount, however, demanded a

change. The ending was considered too

downbeat and depressing. New scenes were

shot, and the ending was re-edited. In

the final version, Longworth’s bullet hits nothing but dust. Luisa lives. She rides out of town with Rio, and they say a sappy goodbye at the

beach, Rio promising to return in time for the birth of their baby.

If that ending sounds

tacked-on and schmaltzy on paper, it plays even worse on screen. The viewer is left with a saccharine

sentiment incongruous with the bulk of the film. On the other hand, for a movie whose outstanding

feature may be its artistic ambivalence, the ending is just about right.

(Eve Goldberg is a writer and filmmaker. Her

articles have appeared in Hippocampus, The Gay & Lesbian Review, The

Reading Room and AmericanPopularCulture.com. Her film and television

credits include Emmy-nominated Legacy of the Hollywood Blacklist, and Cover Up:

Behind the Iran-Contra Affair. Her first book, Hollywood Hang Ten, is a

mystery novel set in 1963 Los Angeles. See a sampling of her short films on her web site at https://eve-goldberg.com/

CLICK HERE TO ORDER CRITERION BLU-RAY SPECIAL EDITION FROM AMAZON