BY BRIAN GREENE

“It’s

easy to manipulate men.â€

That’s

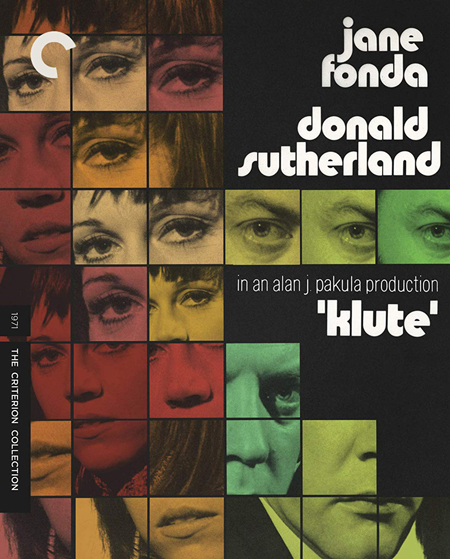

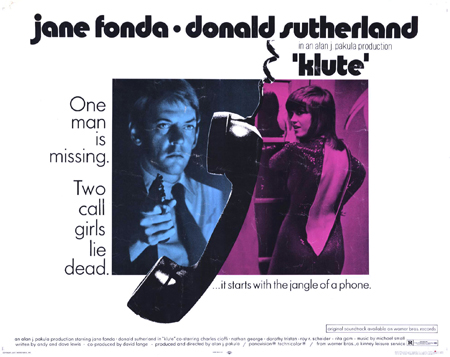

a key line in Alan J. Pakula’s 1971 film Klute, which has just been released in

a new Criterion Collection edition. The line is delivered by a New York City

call girl named Bree Daniels, as portrayed by Jane Fonda, who won a Best

Actress in a Leading Role Oscar for this performance.

“It’s

easy to manipulate men†is a striking declaration, especially when it comes

from the mouth of a paid sexual escort. But some context is necessary here,

because when Daniels utters that line to her psychiatrist – in one of a few

crucial scenes that take place in Daniels’s shrink’s office – she is actually

talking about the one man in her life whom she’s not sure she can control. This

is John Klute (played by Donald Sutherland), a strait-laced fellow from a

no-name town in Pennsylvania. A friend of Klute’s from PA, this guy a

successful businessman and seemingly happily married man, has gone missing. The

FBI has reason to believe his disappearance may be connected to Daniels, whom

he must have met while on a business trip in New York and to whom he appears to

have a perverted fascination. When the feds can’t locate the missing man, the

family, in conjunction with a business associate, hires his friend Klute to go

to the big city and work through the call girl in an attempt to track him down.

But much more happens between Klute and Daniels than them joining efforts to

solve the mystery of the vanished man. And this disturbs the escort, who is

comfortably accustomed to being able to remain emotionally detached in her

relations to members of the opposite sex.

To

a great extent, Klute is a film driven by contrasts. The contrast between the

apparently normal lifestyle led by the missing man, with the more sordid,

sinister doings he appears to have gotten up to in his interactions with the

New York call girl. The contrast between the reserved, repressed Klute and the

expressive, psychologically volatile, sexually liberated Daniels. The contrast

between Daniels’s life as an escort, where she is in command of the men who pay

for her company and sexual favors, and her endeavors to break into acting,

where she is shown to be just another face in the crowd, and unwanted. The contrast between the movie’s overall

somber, eerie tones with the Bacchanalian, seedy atmosphere in the club scenes.

The contrast between the story’s suspense film elements and its following of an

unconventional romance.

It’s

odd that the movie is called Klute. Because that suggests that the tight-lipped

detective-for-hire is the most central character. Anyone who’s viewed Klute

knows that the story revolves around Daniels, and that John Klute is just

another person who’s transfixed by the unpredictable doings of the complicated,

dynamic call girl. Fonda, who was reluctant to take the role of Daniels, to the

point of telling Pakula he should forget about her and cast Faye Dunaway

instead, wound up owning the part. Sutherland is also impressive in playing the

enigmatic Klute in a manner that makes him the ultimate interpersonal challenge

to Daniels.

There

aren’t many significant supporting roles in the film, but among the few, both

Roy Scheider (Daniels’s former pimp) and Charles Cioffi (the business executive

man who oversees Klute’s mission) are convincing. Rita Gam makes a memorable,

if brief, appearance as a madam, and it’s an unexpected treat to see Jean “Edith Bunkerâ€

Stapleton in a bit part. Director of Photography Gordon Willis’s

darkness-oriented work is spot-on, and Michael Small’s experimental, effective

score sounds like it could be music provided by Ennio Morricone for an Italian

giallo thriller.

In

all, Klute is a masterwork. It’s a stunning achievement for Pakula,

particularly considering that it was only his second directorial effort to date.

It works as an eerie suspense story, but is more deeply satisfying as a

character study of a believable, intriguing, complex woman. It perfectly set

the tone for what would become known as Pakula’s “paranoid trilogy,†the other

titles being The Parallax View (1974) and All the President’s Men (’76).

Regarding

the Criterion extras, the transfer looks beautiful, as one would expect. Mark

Harris’s booklet essay is somewhat interesting, but the better part of that

packaging is the set of eye-opening excerpts from a 1972 Sight & Sound

interview with Pakula.

The

first of the featurettes is 20 minutes or so from a documentary about Pakula -

this includes current and archival interview snippets with a film historian, a

former student of Pakula’s, Charles Cioffi, and Pakula himself. There’s a new

interview of Fonda by Ileana Douglas; a discussion of the film’s look and style

by a fashion historian; a 1978 TV interview of Pakula by Dick Cavett in which

they discuss Klute and Pakula’s other work as both a film director and producer;

a 1973 interview of Fonda by Midge Mackenzie, this largely centered around

Fonda’s political activism at the time; and, finally, “Klute in New York,†a short documentary

about the making of the film, at the time that it was being put together. Among

the video bonus features, the first few are somewhere between vaguely

interesting and ho-hum, but the Cavett/Pakula and Mackenzie/Fonda interviews

are fascinating and highly worthwhile, as is the “Klute in New Yorkâ€

featurette.

CLICK HERE TO ORDER FROM AMAZON