BY HANK REINEKE

On the surface it appeared somewhat brave of Kino Lorber

to greenlight a Blu-ray edition of Peter Hunt’s 1974 conspiracy-thriller Gold. It’s not that the film isn’tt deserving of such treatment, in this case

an almost flawless restoration from original elements courtesy of Pinewood

Studios. It’s only that this film has

already been exhaustively exploited

on peddled by every budget VHS and DVD label over the last several decades. So fans of the film would surely have this

title – perhaps in multiple editions and action-film multi-packs – already

sitting on their collection shelves. If

so, I can promise your copy is a greatly inferior version to what we’ve been happily

provided with here.

The back story of this film’s production, as so often the

case, is nearly as interesting as the film itself. Michael Klinger, the British film producer

who had given us the great Michael Caine spy thriller Get Carter in 1971, had previously optioned the film rights to such

novels as Gold Mine (1970) and Shout at the Devil (1968). Both of these adventure-thrillers had been

authored by the Rhodesian novelist Wilbur Smith. Smith would, alongside co-writers, later

share screenwriting credit for both films. Klinger was able to raise funds for the film’s production through South

African investments and a promise – soon to be controversial - to shoot both of

his films in Johannesburg and neighboring communities.

Klinger brought on Peter Hunt to direct the film – whose

working title of Gold Mine was soon

shortened to Gold. In doing so, Klinger would not-so-coincidentally

rescue Hunt’s career as a director of big-screen adventures. Following production of the Hunt helmed sixth

James Bond film On Her Majesty’s Secret

Service (1969), the former editor was sadly offered only two subsequent

directorial assignments, both far more modest efforts for British television. In what everyone hoped would be his deserved

return to big screen respectability, Hunt would bring on a number of veterans

from the James Bond series to assist him on his return to big feature

filmmaking: editor John Glen, sound

recordist Gordon K. McCallum, camera operator Alec Mills, title artist Maurice

Binder and production designer Syd Cain amongst them.

It was likely a Godsend to Cain that he wasn’t tasked to

replicate an actual working mine in full scale. Klinger had been able to secure the full cooperation of South Africa’s

General Mining Corporation for the film’s production. The British souvenir program for Gold, later sold at cinemas in the UK, boasted

that the GMC was “one of the great mining and finance houses in the world,â€

adding the production team was given unfettered use of their mines at West Rand

and Bufflesfontein. It was at the latter

location that most of the surface photography was shot, with filming having

commenced “beneath the 160-foot high shafthead and above the 500 miles of

tunnels which twist 9,000 feet below and from which are torn 5,000 metric tons

of rock every month.†Cain did impressively replicate portions of the gold mine to film interior action scenes at Pinewood Studios.

Tapped to portray Rod Slater, was another – if more

recent – member of the James Bond film family: Roger Moore. Moore’s character in

the film was recently promoted – or perhaps one should say “set up†– from

“Underground Manger†to General Manager of Sonderditch GMC Ltd. It’s a South

African mining company that will soon fall victim to a nefarious plot hatched in

London by a board room of ruthless financial investors led by Sir John

Gielgud. Their plan is to covertly flood

the mine to manipulate prices on the gold market in an effort to increase their

own fortunes… even if their windfall would come at the at the expense of the

miner’s lives. I’m not giving away anything here, this film is by no means a

mystery; the protagonists are identified nearly from the film’s very beginning. Gielgud has many accomplices in his plot

including the mine’s very own Managing Director Manfred Steyner (Bradford

Dillman).

There was little doubt that the producers of Gold hoped their film might ride the

coattails of Moore’s surprising international success as James Bond in Live and Let Die (1973). The lobby cards

for Gold, one guesses not

unintentionally, would boast “Everything They Touch Turns to Excitement!†Which may have been a great line of ballyhoo,

but one whose promotional zing would seem awfully familiar to the one found on the

Goldfinger (1964) one sheet: “Everything

He Touches Turns to Excitement!†I

suppose it can also be argued that Gielgud’s intention to create a crisis to

manipulate gold prices and increase his fortune by “five thousand million

dollars†(whatever amount that is) is essentially an idea torn from Auric

Goldfinger’s playbook. Interestingly, Gold would later be paired in the UK as

a double-feature with Diamonds Are

Forever (1971). The very collectible

British Quad poster assembled for this odd cross-studio pairing would trumpet

“At last! Moore and Connery Together in One Terrific All-Action Programme!â€

Moore wasn’t the only actor on hand to bring a little

star power to the marquee. Actress

Susannah York was cast to play Terry Steyner, the Cessna piloting wife of

conspirator Dillman, and Slater’s immediate boss. If Dillman’s Steyner is a complete tool, Moore’s

Slater is, to be honest, a bit of an anti-hero himself: he’s a philandering

rapscallion, who carries a checkered past of broken marriages, debt and

high-living tastes that he can ill afford. Moore easily seduces York and their ill-advised affair begins... though,

to be fair, she was desperately unhappy in her marriage to begin with. Ray Milland, who plays York’s father, is also

on hand as the curmudgeonly but amiable CEO of Sonderditch. Also working on the

film was famed composer Elmer Bernstein, whose emotive score would earn him (and

lyricist Don Black) an Academy Award nomination in the Best Music, Original

Song for “Wherever Love Takes Meâ€â€¦ but they would lose out to “We May Never

Love Like This Again†from The Towering

Inferno.

So the film certainly doesn’t lack for talent. The problem with Gold is that the story is a maddeningly meandering slow burn. Every stage of the nefarious plan and every criminal

and marital double-cross is dutifully documented at length… at the expense of

the film’s action which is relegated to the film’s final fifteen minutes. Hunt’s best and most dramatic moments are captured

in scenes involving the dangers of the dank, claustrophobic mines, all groaning

beams of lumber, dynamite fuses, trapped miners and unsettling cave-in catastrophes

(one which includes a grim on-site medical amputation).

As already mentioned, there were a lot of film

technicians associated with the James Bond franchise who would work on Gold. The most notable, perhaps, was this film’s Editor and Second Unit

director John Glen. There’s little doubt

that this film would later prove influential to Glen when chosen to direct the fourteenth

Bond film A View to a Kill

(1985). Much of the visual mayhem on

display in Max Zorin’s soundstage mine was eerily similar to those in Hunt’s Gold. Glen would go on to direct Moore in three James Bond adventures from

1981-1985. Hunt, on the other hand, had

previously worked with Moore on a single episode of The Persuaders (“Chain of Events,†1971), but would work again with

the actor on Gold and Shout at the Devil (1976). Despite their friendship, Hunt would confess

in a fascinating interview with the short-lived sci-fi magazine Retro Vision, “I love Roger, he’s a

lovely man and I’ve done three films with him. But he was never my idea of James Bond.â€

The World Charity Premiere (“In Aid of the Star

Organisation for Spasticsâ€) of Gold

was held on the evening of Thursday, September 5, 1974 at the Odeon Leicester

Square. On Friday, September 6th,

the film was to set to enjoy a limited roll out to just short of two-dozen

theaters across the UK. Hemdale, the corporation

set to distribute the film in the UK afterwards took out a full-page ad in the

trades trumpeting “Gold is proving to

be 24 carat – 1st Week Box-Office Total in 23 Cinemas: 81, 660

GBP. Every situation held over. Mr. Exhibitor Make Sure You Get Your Share of

Gold.†The film would make less of a splash in the

U.S. Though the US would not see a

version of the colorful souvenir program brochure that British audiences were

offered, Pyramid Books would publish a paperback movie tie-in with a promise

their pulp edition would include “an 8-page photo insert from the film.â€

Unfortunately for the producers, critical reaction to the

film in the U.S. was less enthusiastic, with many newspapers writing off Gold as one more run-of-the-mill

“disaster films.†There was some morsel of truth in that. The success of The Poseidon Adventure (1972) had kicked-off in its wake a rash of

box-office and pop-culture disaster-film successes as The Towering Inferno (1974) and Earthquake!

(1974). One critic would, incorrectly,

but understandably, describe Hunt’s adaptation of Gold “as one of the cataclysm of disaster movies that have lately

been making cinemas look like Red Cross centers.â€

Most of the criticism directed at the film was not due to

the film’s worthiness as a big screen adventure, but more the result of real

world global contemporary politics. The

film was shot, despite a boycott by both British film industry unions and

anti-apartheid groups worldwide, in apartheid South Africa. Moore would later reflect (or, perhaps,

deflect) that, in his opinion, Gold

“was a film without any political message.†It was his contention that blacks

and whites had worked amiably together to help bring the adventure to the big

screen… though the film certainly captures sad glimpses of this desperately

segregated society whenever black and white South Africans would mutually

converge, well separated, at such public events as a soccer match, a dance

exhibition or an awards ceremony. The Philadelphia Inquirer suggested, “Gold contains some deft allusions to

apartheid without ever confronting it.†A more chastising rebuke of the

filmmaker’s perceived ignorance of the political implications of shooting in

Johannesburg would come courtesy of the Washington

Post: “The film is certainly timid

and naïve in political terms, since all the filmmakers are prepared to appeal

for is racial amity and benevolent white ownership.â€

Vincent Canby of the New

York Times was particularly virulent in his appraisal, decrying not only

the unseemly political aspects of the film’s production, but also the film as

art. Canby would reveal more than a

measure of critical shortsightedness when he described Hunt’s magnificent On Her Majesty’s Secret Service as “the

worst Bond film ever,†a ridiculous charge if there ever was one… but then

again the esteemed critic didn’t live long enough to despair through Quantum of Solace. Canby was particularly disparaging of some of

Hunt’s more artistic use of the camera. In one sequence in the film, the camera sits fixed behind the diffusion

of brandy glass. In Canby’s assessment,

such diffusion was purposefully chosen by Hunt as he was likely “embarrassed by

the content of the film and trying his best to hide it.â€

To make matters worse, on a New York City publicity swing

for Gold, Susannah York was visited

by critic Rex Reed in her Manhattan apartment. It was a swanky world away from the mines of Johannesburg, and her

experience working with the Bantu and Zulu miners had re-ignited her already

well-documented reputation as a liberal free-spirit. “When I was in South Africa, I was so

appalled at the apartheid segregation,†she conceded. “The oppression is terrible there.†She added

that during location shooting she had intentionally “went down into the mines

and visited the miner’s camps where they sleep twenty to a room with a stove in

the center eighteen months at a time.†She learned from the miners who were employed as set dressing that they

were not allowed to have their wives or families visit while contracted to

work. “What a terrible life for just a

pittance,†York sighed.

Needless to say, the publicity unit working tirelessly to

promote the film in the U.S. might have preferred the actress stayed away from

politics. But, ultimately, whether due

to politics or audience disinterest, the film would under-perform in the United

States. The film would make more of an impression on U.S. viewers in 1978 when

it was screened as one of ABC-TV’s “Sunday Night Movies.†This movie is neither Moore’s nor Peter

Hunt’s best film by a margin, but the film’s own margins accidentally provide

an interesting historical snapshot of South Africa during an era passed.

This Kino Lorber Studio Classics Blu-ray of Gold features a 1920x1080p 2.35:1

transfer and DTS audio with removable English subtitles. The set features eight chapter selections, as

well as the film’s original theatrical trailer. Also included are trailers from several of Kino’s other releases: The Naked Face (Moore), The Killing of Sister George (York), Panic in Year Zero (Milland), Chosen Survivors (Dillman) and The Wicked Lady (Gielgud). There’s also an audio commentary by film

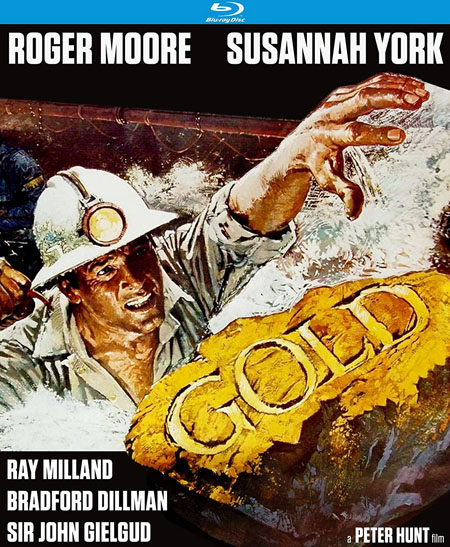

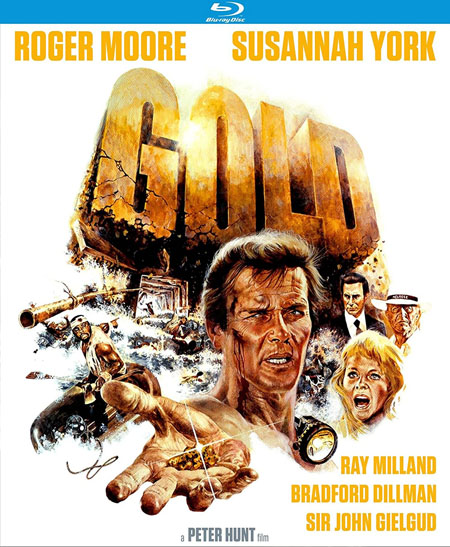

historians and filmmakers Howard S. Berger and Nathaniel Thompson and reversible sleeve art.

CLICK HERE TO ORDER FROM AMAZON