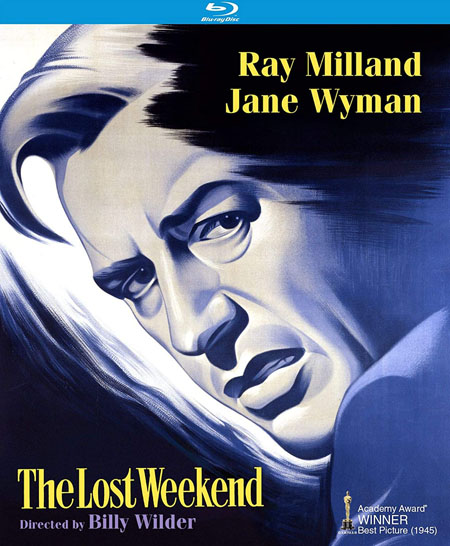

“THE

DTs IN HIGH DEFINITIONâ€

By

Raymond Benson

In

1945, Billy Wilder’s The Lost Weekend was a big deal. If it wasn’t the

first Hollywood movie to portray alcoholism as a serious problem, then it was

certainly the most visible and influential one.

In

the latter 1940s, Hollywood’s output changed from the sunshine-feel

good-entertainments that the Golden Age had produced in the 30s and early 40s.

American GIs came home from the war, and many were disillusioned and cynical.

The war was the catalyst for Americans to “grow up.†They were ready to accept

more serious, darker fare. Thus, we got film noir—crime pictures that

were full of angst and betrayals—and we got the “social problem film.†The

latter tackled subjects that Hollywood had previously never touched—alcoholism,

racism, anti-Semitism, government corruption, and drug abuse. Titles like Gentleman’s

Agreement, All the King’s Men, Pinky, and The Lost Weekend,

which kick-started the trend.

Starring

Ray Milland in a harrowing performance as Don Birnam, a hopeless drunk in

Manhattan, the picture presents a “realisticâ€â€”for the time—depiction of a

weekend bender, a binge complete with DTs and night terrors. Jane Wyman costars

as Birnam’s long-suffering girlfriend, Helen. From the get-go, she sympathizes

with Birnam and haplessly attempts to help him with his problem. Birnam’s

brother, Wick (Phillip Terry), also indulges him, although he’s at the point of

giving up.

The

movie’s gritty wake-up call was likely the reason it won the Academy Awards for

Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay (by Wilder and Charles

Brackett, based on the novel by Charles R. Jackson), and Best Actor (Milland).

That

said, today The Lost Weekend has problems. Billy Wilder was one of the

great Hollywood writer-directors, and his handling of the material is fine.

Milland deserved his Oscar win, although he’s often over the top—which perhaps

underscored the horror of the film’s subject matter. The difficulty that

today’s audiences will have with the film is its naivete. For one thing, Helen must

be nuts and a glutton for punishment to stick around Birnam for over three

years. The biggest sin is the abrupt “everything’s going to be okay†ending,

which will assuredly cause one’s eyes to roll.

In

many ways, there’s not too fine a line between The Lost Weekend and some

of the better cheap exploitation films about drug abuse and teen sex that were

made outside of Hollywood and were exhibited in the manner of a sleazy

sideshow. The difference is that Weekend had a big budget, stars, and

the benefit of being backed by a major studio and was made in Hollywood. The sensationalism

and morality-play aspects, though, are the same.

Kino

Lorber’s new high definition restoration looks darned good, despite some visual

artifacts here and there. The audio commentary by film historian Joseph McBride

delves into the production history and offers interesting anecdotes. The

supplements include the complete radio adaptation starring Milland and Wyman,

plus a “Trailers from Hell†segment with Mark Pellington narrating. Theatrical

trailers for this and other Kino Lorber releases round out the package.

Make

no mistake—The Lost Weekend is an important American picture that broke

new ground. One must always judge a movie within the context of when it was

made and released. Nevertheless, 75 years has not been kind to the film.

For

fans of Billy Wilder, cinema history, and a stiff drink.

CLICK HERE TO ORDER FROM AMAZON