“THE

MASTER OF SURREALISMâ€

By

Raymond Benson

Today

we might say that David Lynch is the foremost purveyor of surrealism in the

arts; but he inherited that mantle from the late, great Luis Buñuel,

who was one of the fathers of the surrealist movement in Europe in the

1920s.

What

is surrealism, you ask? You probably “know it when you see it,†but the true

definition, as imposed by the surrealists who made it a thing, is to

portray in an artistic expression the nature of dreams. That can be in

paintings (Salvador DalÃ, Max Ernst), theatre (Jean

Cocteau), photography (Man Ray), and film (Buñuel, along with

others like Cocteau, Germaine Dulac, and more). Surrealism in film may just seem

“weird†to some audiences, but it’s actually satirical, nightmarish, irreverent,

and profound, and it can be a commentary on the real, contemporary world.

Luis

Buñuel was indeed the master of cinematic

surrealism. From his debut short silent picture, Un Chien Andalou (1929),

that he co-directed with Salvador DalÃ, through such titles

as Los olvidados (The Young and the Damned; 1950), Viridiana (1961),

and Belle de jour (1967), Buñuel challenged

audiences with often brilliant, sometimes confounding work that was

controversial, hilarious, and political. Poor Buñuel had to move from

one country to another because he’d sometimes make a film that the authorities

found objectionable, so he’d go somewhere else—and then rinse and repeat.

Mostly, though, he worked in France, Mexico, and his native Spain.

In

the 1970s, Buñuel himself was in his seventies, and he made

three of his most acclaimed masterpieces; in fact, they were his final three

movies. They were French/Spanish co-productions, utilizing casts and crews from

both countries, many of whom worked on more than one of these and in some cases

all three. Produced by Serge Silberman, the titles serve as something of a

trilogy, although in truth they are unrelated.

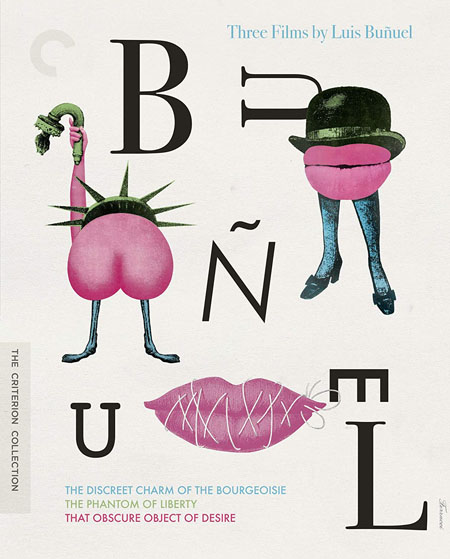

The

Criterion Collection has released a new box set containing all three films in

high definition, upgraded from earlier, separate DVD releases. It is, frankly,

an abundance of riches.

The

Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (Le Charme discret de la bourgeoisie;

1972) is arguably Buñuel’s most well-known title. It deservedly

won the Oscar that year for Best Foreign Language Film, and it was also

nominated in the Original Screenplay category (written by Buñuel

and longtime collaborator Jean-Claude Carrière). With an all-star

French and Spanish cast consisting of the likes of Fernando Rey, Delphine

Seyrig, Jean-Pierre Cassel, Paul Frankeur, Bulle Ogier, Stéphane

Audran, and Michel Piccoli, Discreet is the story—if one can call it

that—of a group of wealthy friends who are always attempting to get together

for dinner, but their plans are consistently interrupted. Sometimes it’s

because the scene is taking place in one person’s dream and it goes haywire, or

perhaps it’s because one of the host couples decide to ignore their guests, run

off, and have sex in the garden. The bourgeoisie, in this case, are the snobs,

the “hoity-toity,†the pretentious upper-class people of Parisian society—and

they are Buñuel’s targets. The episodic absurdities are funny

and strange, but ultimately delightfully cockeyed.

The

Phantom of Liberty (Le

Fantôme de la liberté;

1974) takes the dark comedy of Discreet and goes a couple of steps

further. Phantom is a series of vignettes—sketches, really—tied together

only by an element from the preceding sketch. For example, a character from one

vignette might leave the room, get in a car, and arrive in a new sketch to

interact with a whole new group of people and a different situation. Again, the

cast is international (Bond film fans will recognize Bond-villain-actors Adolfo

Celi and Michel Lonsdale in the cast), with many of the same personnel from Discreet.

The sequences here are more acerbic and sometimes shocking, and always a

comment on incongruities of society. For example, in one dinner party scene,

the guests are seated around the dining table on toilets (and, yes, the women

lift their dresses, and the men pull down their pants to sit at the table).

However, no food is served. During the conversation, each guest must quietly ask

the hostess “where the dining room is,†(“Oh, it’s down the hall, first door on

your leftâ€), where the guest goes into a stall, is served a plate of food from

a dumb waiter, and proceeds to eat dinner in private! (“It’s occupied!†one

diner proclaims when another guest knocks on the door.) Wild stuff.

That

Obscure Object of Desire (Cet obscure objet du désir; 1977) was Buñuel’s last film. It

was nominated for the Best Foreign Film and Adapted Screenplay Oscars, but it

did not win. It is a little more conventional than the previous two pictures

with one exception. The character of Conchita, the “obscure object of desireâ€

of the title, is played by two different actresses (Carole Bouquet, four years

prior to appearing in the Bond film For Your Eyes Only, and Ãngela

Molina). There are sequences, for example, in which Conchita, played by Bouquet,

goes out the door and then immediately returns, but this time it’s Molina as

the same character. Fernando Rey is Mathieu, an older, wealthy man who has met

Conchita and fallen head over heels for her. He spends the entire movie alternately

frustrated and mesmerized by the woman, who leads him on, resists him, tempts

him, and plays hard to get. It isn’t long before we realize that Buñuel

is making a blatant statement on the nature of male/female relationships and

who really has the upper hand in them. It’s a fascinating, sometimes erotic,

and insightful piece of work.

Criterion’s

3-disk Blu-ray set presents all three films in new high-definition digital

restorations with uncompressed monaural soundtracks. The distinctive 1970s film

stock is quite evident, but the images are much improved over the previous DVD

editions. Supplements are bountiful, way too many to list here (all the extras

from the DVDs are ported over, and there are many additions on each disk).

There are several documentaries about Buñuel, some of which

are feature-length, and vintage “making of†featurettes. Interviews with a

selection of Buñuel’s colleagues, such as co-writer Carrière,

are fascinating. The thick booklet contains essays by critic Adrian Martin and

novelist/critic Gary Indiana, along with interviews with Buñuel.

Three

Films by Luis Buñuel is highly recommended for fans of art

house cinema, unconventional narrative, black humor, and exquisite oddities

that you just don’t see every day.

CLICK HERE TO ORDER FROM AMAZON