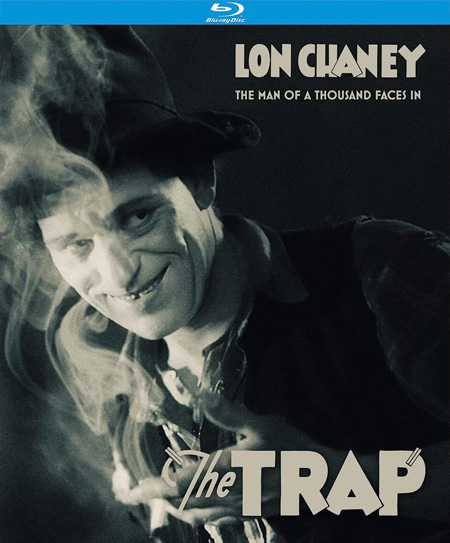

By Hank Reineke

The working title of the Universal-Jewel silent

six-reeler The Trap (1922) was Wolf Breed – for reasons that will soon

become apparent. Lon Chaney’s feature

role casting was reported during the first week of September 1921, the film

reportedly to be based on a scenario by Lucien Hubbard. The film was apparently

still in production during late September/early October of 1921. Newspapers were reporting that immediately following

Chaney’s completion of Wolf Breed, the

actor “will appear in The Octave of

Claudius for Goldwyn.” That film would in fact be made, but released as The Blind Bargain (1922), directed by

Wallace Worsley - who would later helm Chaney’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Along with London after Midnight

(1927), The Blind Bargain is

inarguably the most sought after of the actor’s lost films.

The

Trap,

by any measure, is a more modest effort than any of the aforementioned trio of

films. The photoplay features Lon Chaney

as Gaspard the Good. His character is so

named as he is a kind and gentle soul. He’s a simple-living, always smiling, bubbly effervescent personality - a

man of good-standing in the small idyllic French Canadian mountain village of

Grand Bellaire. But Gaspard’s usual pleasant

demeanor will soon sour. Returning to

the village from a recent trip, Gaspard discovers that he has not only lost his

girlfriend Thalie (Dagmar Godowsky) to a seemingly well-to-do carpetbagger

named Benson (Alan Hale), but also to his unregistered claim to his pappy’s

hyacinth gemstone mine. Gaspard tries his best to sublimate his personal sorrows,

one title card noting while “The morning sun was no more radiant,” the broken-spirited

Gaspard managed to hold “no malice” within his heart. For a time, anyway.

But things change in the intervening span of seven – yes,

seven – years. The cad Benson has suffered several reversals

of fortunes, beginning with a calamitous cave-in dooming his mining

operation. We also learn Benson has not

been a particularly loving husband to sweet Thalie who we watch as she succumbs

to a fatal illness. Her husband coldly

dismisses his wife’s deathbed lethargy to “laziness.” Sitting astride Thalie’s bedside is her grieving

five-year old son with Benson, “The Boy” (Stanley Goethals). Gaspard too has suffered a shocking reversal

– a shift in personality as the last few years events have left him bitter. Though Benson’s recent streak of bad breaks

should have brought Gaspard a measure of satisfying yin and yang closure, it’s

simply wasn’t enough to erase the sting of his personal anguishes.

So seeking a more punishing revenge on Benson, Gaspard

convinces a local tavern tough that the carpetbagger has been saying awful

things about him. The enraged brute

attempts to assail Benson who unexpectedly defends himself with a pistol shot –

a crime for which he is sentenced to the gallows. But this sentence is later commuted to a

prison sentence when the brute survives the shooting. In the interim, and as per Thalie’s deathbed

wish, Gaspard has taken custody of her son - for whom the bitter ex-lover intends

to administer a misplaced vengeance. But

in short time the innocent “wee waif” reawakens the good in Gaspard’s heart who

becomes a doting model foster parent to the child. But when Gaspard is informed that Benson has

been released from prison with plans to collect his biological son, a

distraught Gaspard - fearful of losing the boy - sets up a diabolical snare involving

a trap door and a starving wolf lying in wait.

It’s a melodrama for sure. In its review of May 20, 1922, Billboard suggested while the storyline

of The Trap was overly “trite,” the

film itself was visually appealing with “most picturesque locations” and

“photography showing some rare and perfect gems of outdoor beauty.” (The film was actually photographed not in

the Canadian wilderness but in the tranquil and majestic canyons of Yosemite

National Park). Chaney’s “remarkable

impersonation” of the French-Canadian Gaspard was noteworthy, even though the

review concedes “the vehicle is not sufficiently strong to do justice to the

ability of the star.” This contrasts

with the view of Variety’s critic who

thought director Robert Thornby’s excessive use of full-frame close-ups of

Chaney – which allowed a bit too much melodramatic over-emoting on the actor’s

part – was nothing if not “tiresome.” Personally,

I disagree with this assessment. Though

there are no shortage of such close-ups, Chaney’s facial expressions on screen enable

the actor to convey emotions of sorrow, joy, malice and anger in a visual manner

that no title card could ever convey as successfully.

That said, The Trap

was an idiosyncratic picture in some sense, and certainly an archetype of the

tortured character roles Chaney would more famously play in the future. Many silent pictures of the day were structured

around romantic angles in their scenarios. But following Gaspard’s loss of both mine and sweetheart Thalie (the

actress being the daughter of the famed Lithuanian-American classical pianist

Leopold Godowsky), the film drops any pretension of romantic conciliation or

renewal. The movie instead focuses on

Chaney’s dark, methodically-plotted and coldly calculated plan of revenge.

Chaney’s real-life “everyman” looks would guarantee his

future was not in his casting as a dashing, romantic matinee idol. The actor was instead more often cast as a

villain or scoundrel or someone living on society’s edges – but one harboring a

conflicted - and occasionally even tender-hearted - soul. The

Trap allows Chaney to move beyond a one dimensional character to more fully

explore the psyche of an aggrieved person’s multi-faceted personality. As a review of The Trap in the Salt Lake

Tribune allows: “You will see and learn to love another side of Lon Chaney

in this picture, as well as despise the old side that we are all so familiar

with.”

If one is to believe an item as reported in the San Francisco Chronicle, there was a bit

of on-set controversy when five-year old - and long-locked - Stanley Goethals

went for a haircut during filming. This simple

act caused the filmmakers considerable consternation. There would now be continuity issues as they

still were still in need of photographing insert shots of the child actor. Though actresses Godowsky and Irene Rich (who

plays a school teacher in the film) coddled the child, even remarking how “very

pretty” his new bob appeared to them, Chaney - while diplomatic - remained firmly

professional in his reaction to the news. He reportedly told the child, “Now, Mr. Goethals, don’t you think a

regular guy like yourself, a chap’s that’s playing a big part in a picture, has

a duty to his art?”

When the film was belatedly released in Great Britain in

October of 1922, The Trap was

re-titled The Heart of a Wolf, and

promoted as “A Story of Reckless Adventure.” Which was admittedly a more exciting enticement than the U.S. ad copy

which only offered the film as “A Story of the Great North Woods.” On the other hand, it was the promotional U.S.

advertisements for The Trap that were

among the first to celebrate and anoint Chaney as “The Man of a Thousand

Faces.” (There were even some earlier ads promoting the actor as the man of “a Million Faces – which may have been

taking the sobriquet a bit too far). But

it’s of interest that the ghastly and iconic Chaney make-up creations for such

characters as Hugo’s Quasimodo and Leroux’s Phantom of the Opera, were still in

the actor’s future. They had no role in

his acquisition of the famous “Man of a Thousand Faces” appellation.

Though the notices of The

Trap ranged from general middling praise to slightly unfavorable, the film managed

to do well at the box-office due – possibly due to the ascending big screen

popularity of Chaney. The trades were

reporting “overflow audiences” in the first half of May 1922 with the film

showing better than average staying power through mid-June. When the film reached cities in the Midwest

in August, Variety reported theater

owners were reporting “Sunday business” of The

Trap “was the best of the summer and held up satisfactorily during the

week.”

Even if one diligently searches through old newspaper and

trade publication archives, film industry reportage from the early twenties

often offers contradictory information. But clippings seem to suggest that initial casting for The Trap commenced in September of 1921

with principal photography following in late autumn of the same year. It wasn’t until a Houston Post item - published in late January 1922 - confirmed that

Chaney had “finished the picture” (still titled Wolf Breed) “for which he was especially engaged by

Universal.”

Other news sources indicate that following the wrapping

of The Trap, Chaney was to go

directly into production of another Universal-Jewel feature, one with the

working title of Bittersweet. That film was to be directed by Lambert

Hillyer, who had previously worked with Chaney on the five-reel western for

Paramount-Artcraft Riddle Gwane

(1918) – of which only fragments survive. The title of Bittersweet was

eventually dropped in favor of The Shock,

that picture released in the early summer of 1923.

It’s fair to note that even in this age of near-instant accessible

information, it’s often difficult to satisfactorily trace the production

chronologies and accurate release dates of many silent-era films. Chaney would reportedly appear in no fewer

than twelve films released in the years 1922-1923 – possibly more in as-of-yet

unidentified bit parts. As a news item

from the Des Moines Register (October

30, 1921) accurately assessed, “Lon Chaney is almost the busiest of players in

Hollywood this year. He hardly finishes

one engagement when he has to ruch [sic] on another.” If one is interested in Chaney’s filmography,

the lonchaney.org website of historian Jon C. Mirsalis (the producer of last

year’s Before the Thousand Faces Vol. 2 Blu-ray of early rarities) and

the several exhaustively researched books on Chaney by author Michael F. Blake remain

the essential references.

On a side note: this 1922 effort was not the first time

Chaney would appear in a film titled The

Trap. Silent-era film historians

suggest Chaney had earlier appeared with actress Cleo Madison in a one-reeler also

titled The Trap, this particular film

lensed courtesy of Powers Picture Plays, an indie entity of Universal’s Film

Manufacturing Co., Inc. Moving Picture News of September 27,

1913 indicates that this particular photoplay “drama” was to first see release

on October 3, 1913 – though Chaney biographer Blake notes even this dating is

in doubt: the Universal Picture Code book indicates the release date as October

26, 1913. As The Trap of 1913 is now believed a lost film – and with the

survival plausibility of one-hundred-and-ten year old nitrate prints being what

they are - there’s very little information on this particular picture to

reference.

Oh, well. At least

we have this Kino Lorber Blu-ray of The

Trap (1922) that is nothing short of magnificent. The film has received a well-deserved 4K

restoration by the owners of Universal Pictures, the best elements sourced from

a tinted 16mm print held by the Packard Humanities Institute and a second 16mm

print held by the British Film Institute National Archive. Though most of the film is seen through a

sepia-toned prism, there are a few scenes where the color abruptly switches to a

blue or olive-green screen. There’s very

little damage present aside from a few fleeting rough patches and un-buffed black

base scratches. Music for this particular

release was freshly composed by television and film composer and arranger Kevin

Lax.

Though there is no booklet accompanying this set, there

are two notable bonus features: the

first is one of the earliest Chaney silents that has survived, By the Sun’s Rays (Nestor-Universal,

1914), an eleven minute two-reeler, with Chaney playing a swindling clerk at a

western gold-mine office. (Only

fragments of two earlier Chaney appearances are known to have survived: Poor Jake’s Demise (1913) and The Tragedy of Whispering Creek (1914),

both in the possession of European film archives).

The second feature is Bret Wood’s Behind the Mask, a sixty-five minute documentary of Chaney’s legendary

career. The documentary first appeared

on a Kino VHS in 1995 as one of eight tapes comprising their

decoratively-packaged Lon Chaney Collection. (That tape also included, incidentally, an early VHS appearance of By the Sun’s Rays). In recent years Kino Lorber has given us very

satisfying Chaney Blu ray issues of The

Phantom of the Opera, The Hunchback

of Notre Dame, The Penalty, Outside the Law, Broadway Love (this one only available as part of their Pioneers: First Women Filmmakers Blu-ray

set) and, now The Trap. With Kino leading the way with the releasing

of Lon Chaney’s feature films, and Ben Model’s silent-film specialist

Undercrank Productions bringing Blu-ray attention to the surviving elements of

Chaney’s films circa 1914-1917, this recent decade of home video has certainly been

a great one for fans of the Man of a Thousand Faces.

Click here to order from Amazon