“NICE

DAY FOR A PICNIC”

By

Raymond Benson

Filmmaker

Nicolas Roeg always managed to challenge cinematic norms. Even his most

accessible and popular film, Don’t Look Now (1973), still had what some

might call “arty” shots and experimental editing. Roeg was a director who loved

the images the camera caught, but he also enjoyed manipulating the narrative of

his pictures with the kind of radical editing likely inspired by the French New

Wave, but probably more by the so-called New American Cinema movement that included

revolutionary filmmakers such as Andy Warhol, Stan Brakhage, and others.

Roeg

began his work in film as a cinematographer—and a very good one, too (second

unit on Lawrence of Arabia, The Masque of the Red Death, Far

from the Madding Crowd, and more). After a co-directing (with Donald

Cammell) debut of Performance (1970), Roeg struck out on his own and

made a name for himself as a director of provocative art house fare.

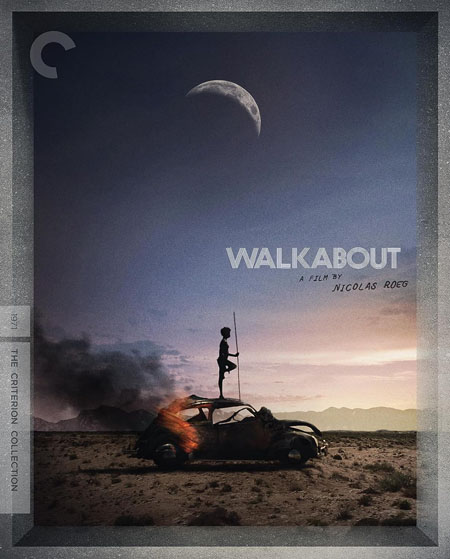

First

out of the gate was Walkabout (1971). It was Australia’s official entry

to the Cannes Film Festival that year, despite it being primarily a British

production (and Roeg himself being English). It was based on the 1959 novel by

James Vance Marshall (a pseudonym of Donald G. Payne), which was first

published as The Children but subsequently renamed Walkabout.

Roeg had apparently wanted to adapt the book into a film for years, and he

finally got the chance to do it with only a million dollar budget. Producers

Max L. Raab and Si Litvinoff (both known primarily as executive producers of

Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, because they had initially owned the film

rights) provided the funding for what was essentially an independent

production, eventually released by 20th Century Fox. Playwright Edward Bond wrote

a treatment that acted as the screenplay, but most of the picture was

improvised on the go.

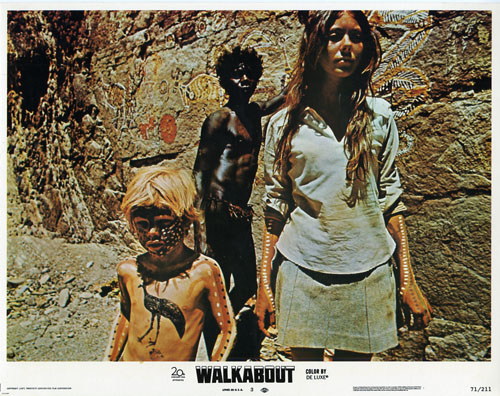

Taking

a minimal crew and a cast of unknowns into the Australian outback, Roeg gave us

a haunting, enigmatic, gorgeous-to-look-at, existential treatise on innocence,

the loss of it, and the importance of communication.

“Girl”

(a young Jenny Agutter, who was sixteen when the film was made) and “White Boy”

(Nicolas Roeg’s son Luc Roeg, credited as Lucien John, who was age seven during

production) are siblings who live what appear to be “normal” lives with their

parents in Sydney. One nice, sunny day, “Father” (John Meillon), takes the two

children to the desert for a picnic. There, he attempts to shoot them, but Girl

protects her younger brother and they hide. Father kills himself and sets the

family car on fire. The two kids are now stranded in the outback. Lacking

survival skills, they manage to make it through a few days (but time is never

clear in the film). Then they meet a young “Black Boy” (Australian and Yolngu

actor David Gulpilil, whose age was unknown at the time but since estimated to

be about eighteen when cast) who is out in the wilderness alone. He befriends

the two, regardless of a language barrier, and effectively saves the white

kids’ lives by teaching them how to find water and hunt for game to eat. Interestingly,

it is White Boy who is able to communicate with Black Boy through mime and

playful gestures; Girl seems to be at sea when dealing with the human who is

totally foreign to her. Days pass as the trio travels across the striking

landscape, culminating in a moment in which the physical adolescence of Girl

and Black Boy follow a natural course to sexual tension. Black Boy performs his

native “courtship ritual” dance in tribal makeup and clothing for Girl. Not

understanding what he’s doing and fearful of him, Girl rejects him. Revealing

the rest of the tale would certainly be a spoiler.

A

“walkabout” is a rite of passage in Australian Aboriginal society. Adolescent

males must spend six months in the wilderness and survive—or not—to became an

adult. Hence, while Black Boy is likely enacting his own walkabout, the film

becomes a walkabout for Girl and White Boy. There’s a lot going on underneath

the surface here, including an examination of race and class differences in a

land where the British Empire encroached on an indigenous people, sexual mores

and taboos, and how one’s social environment dictates how one behaves.

Walkabout

is a

fascinating film, and it was highly praised by critics upon release—but, sadly,

it was a box office failure. It has since become a cult classic and a cinephile

favorite. There was some criticism (still is) of the picture’s display of

nudity of all three leads, seeing that, technically, Agutter and young Roeg

were underage. Some bits were cut for the initial release, but footage was

restored in the 1990s. The British Board of Film Classification, though,

determined that the film was not “indecent.” Agutter herself has contemporarily

defended the nude scenes and says that they are essential to the themes of the

movie.

The

Criterion Collection released the film on DVD and Blu-ray years ago, but now

the company has issued a new 4K UHD edition containing two discs. A 4K UHD digital

master in Dolby Vision HDR occupies the first disc, while a Blu-ray of the film

plus special features are on the second. The visuals are, naturally, stunning. An

audio commentary featuring both Nicolas Roeg and Jenny Agutter accompanies the

film. Special features include vintage interviews with Luc Roeg and Agutter, an

hour long documentary on the life and career of David Gulpilil, and the

theatrical trailer. An essay by author Paul Ryan is in the booklet.

With

John Barry’s lush score, Roeg’s own striking cinematography, the sweeping

panoramas of the Australian outback, and the likable, honest performances by

the cast, Walkabout is a highly recommended must-see.

Click here to order from Amazon