“HE

USED TO BE A BIG SHOT”

By

Raymond Benson

One

of the more popular and enduring genres to come out of Hollywood in the late

silent era and the first fifteen years of talkies was the gangster picture. They

sprung into the public consciousness as a result of Prohibition (late 1919 to

1933), which is when real life gangsters were making a splash in America. Early

Pre-Code gangster movies were shockingly violent and gritty—titles like Little

Caesar (1931), The Public Enemy (1931), and Scarface (1932). After

the Production Code kicked in during the summer of 1934, the genre was still

popular and being churned out (especially by Warner Brothers) but they had been

toned down somewhat with more “likable” gangsters.

James

Cagney became a star as a result of playing a gangster in The Public Enemy,

and a pretty mean one at that. Coming from vaudeville, though, he had other

talents. His real heart was in singing and dancing (he won his only acting

Oscar for doing just that in Yankee Doodle Dandy, 1942). In the late

thirties, he continued to make gangster films but he made a big deal out of

resisting them. When The Roaring Twenties was made in 1939, Cagney

proclaimed that this was his swan song playing such a character. At least it

was for ten years, when he made his one and only gangster comeback in White

Heat (1949).

Panama

Smith (Gladys George) says in The Roaring Twenties, “He used to be a big

shot.” There is no “used to” with James Cagney. He was always a big shot in

Hollywood and on the silver screen, a larger than life actor who commanded

whatever picture he was in. He had charisma in spades, the kind of energy that

could ignite a movie projector’s lighting rods, a voice that would forever be

fodder for impressionists, and a superior talent that many actors today could

only dream about.

It's

no surprise that The Roaring Twenties totally belongs to James Cagney,

even when someone like Humphrey Bogart is co-starring. (At the time Bogart had

yet to star in his own feature film; throughout the thirties he did a lot of

playing second banana.) In fact, The Roaring Twenties was the third and

last picture that Cagney and Bogart made together (the other two being Angels

with Dirty Faces and The Oklahoma Kid, 1938 and 1939, respectively).

The

movie came from a short story, “The World Moves On,” by Mark Hellinger, a

well-known journalist of the time. An info-scroll at the beginning of the movie

tells us that Hellinger based the story on “real people” that he knew, implying

that The Roaring Twenties is a true story, or at least inspired by one.

The story was turned into a screenplay by Jerry Wald, Richard Macauley, and

Robert Rossen. Anatole Litvak was initially hired to direct the movie, but it

was ultimately helmed by Raoul Walsh, who had already made some gangster

pictures and would do more in the future.

Eddie

Bartlett (Cagney), George Hally (Bogart), and Lloyd Hart (Jeffrey Lynn) meet in

a foxhole during World War I and become friends. Upon returning home to New

York City, times are tough for GIs. Eddie and Lloyd start a taxi company and

George goes into crime. Eddie reaches out to the young woman who had written to

him during the war, Jean Sherman (Priscilla Lane), but discovers she’s a bit

too young for him. A couple of years later, though, she’s the right age. By

then, Prohibition has kicked in. Eddie and his good friend Danny (Frank McHugh)

get into the bootlegging business with Panama Smith at a speakeasy. Eddie wants

to marry Jean, but Jean actually has eyes for Lloyd, so there’s a little

triangle thing going on to which Eddie is blind. Eddie eventually partners up

with George, and throughout the “roaring twenties” they make names for

themselves as powerful racketeers. But then things go south, as they always do

in gangster pictures.

The

Roaring Twenties was

one of the more popular movies of 1939. It was a big hit, and in fact it out

grossed The Wizard of Oz at the box office. This is not a surprise, for The

Roaring Twenties is an excellent piece of Hollywood entertainment. It’s

slick, it’s well acted and well directed, and its “epic” in structure, covering

a period of fifteen years, is compelling. It’s also a bit of a musical, too,

with Priscilla Lane adeptly performing a few 1920s-era numbers at the

speakeasy. Today the movie is considered one the best of the 1930s gangster

titles, and for good reason—and that reason is James Cagney. Why the film was

not nominated for a single Academy Award is a mystery.

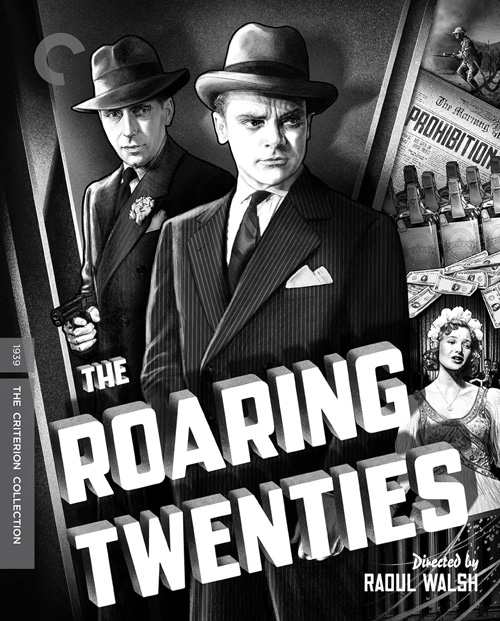

The

Criterion Collection’s new 4K digital restoration with an uncompressed monaural

soundtrack is presented in a twofer package that contains a 4K UHD disk of the film in Dolby Vision HDR, and a

Blu-ray disk with the film and special features. An audio commentary, ported

over from the old Warner Home Video disk, is by film historian Lincoln Hurst. English

subtitles are available for the hearing impaired. The restoration is truly

magnificent, a beauty to behold. The images, shot by DP Ernest Haller, are so

pristine and clean that the movie might have been shot yesterday.

Disappointingly,

the special features are minimal. There is a new interview with critic Gary

Giddins that is interesting enough, and a short vintage 1973 interview with

director Walsh, the theatrical trailer, and that’s it. It’s a shame, really,

that the original Warner DVD’s supplements of the “Warner Night at the Movies”

features—shorts and a cartoon—and hosted by Leonard Maltin, are not included

here. An essay by film critic Mark Asch adorns the booklet.

So,

get on your Fedora and pin-striped suit, or your flapper outfit, and take a

trip back to The Roaring Twenties. Highly recommended for fans of James

Cagney, Humphrey Bogart, gangster pictures, and classic Hollywood studio movies.

Click here to order from Amazon