“WE

HAVE NOTHING TO LOSE BUT OUR FUTURES”

By

Raymond Benson

A

genius has to start somewhere.

A

very young Stanley Kubrick made his first feature film, Fear and Desire (called

The Shape of Fear during production and until it found a distributor),

at the age of twenty-two. It was very much a DIY production. In many ways

it is the epitome of early independent filmmaking, the kind in which a fellow

with a camera goes out to make a movie and then worries about finding a

studio to release it. The picture was financed by family and friends, written

by a school pal (future Broadway playwright Howard Sackler), and cast with

young, struggling New York actors who were willing to work for peanuts. Kubrick

produced and directed the movie, but he also photographed and edited it

himself, too. It took a year-and-a-half to finish, and then he went about

marketing it himself.

The

astonishing thing about all this is that Kubrick was operating on chutzpah.

While he had already made two documentary shorts, he was simply “winging it”

when it came to making a feature length fiction narrative film. What he had on

his side was his cinematographic capabilities. He knew cameras, lighting, and

composition like the back of his hand, for he had spent four years after high

school working as the youngest staff photographer for Look magazine in

New York creating narrative “photo essays,” almost the equivalent of

storyboards. Editing a movie, directing actors, and telling a good story was

another matter… and something he would eventually learn how to do.

Unfortunately, while Fear and Desire looks gorgeous and is indeed a

lesson in photographic composition and lighting, it fails on all the other

aspects of movie making.

Kubrick

himself disowned Fear and Desire not long after its release in 1953. In

fact, he attempted to acquire all existing prints, including the negative, and

burn them. Luckily for film historians and Kubrick aficionados, he was

unsuccessful. The copyright in the movie was owned by Kubrick’s uncle, Martin Perveler,

a fairly wealthy pharmacy owner in California who put up most of the money and

received Associate Producer credit. The feature had disappeared for decades and

was sometimes available on poor quality bootleg VHS tapes and DVDs. It was only

since Kubrick’s death in 1999 that today’s copyright owners and the Library of

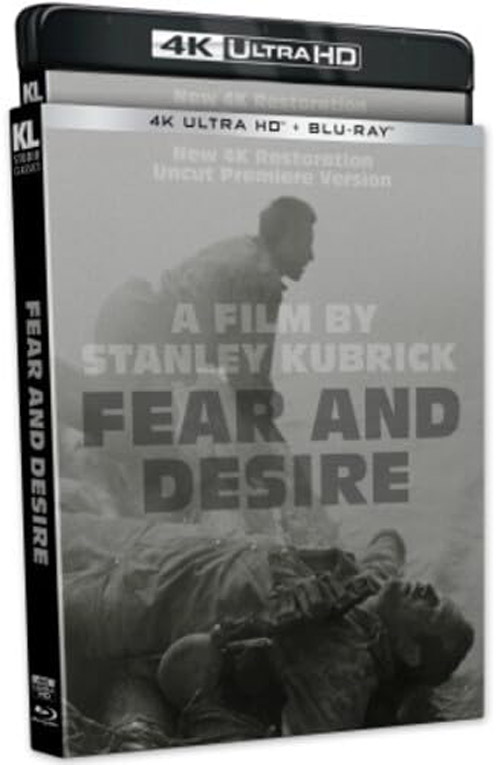

Congress made the movie available. In the USA, Kino Lorber distributed

excellent quality DVD and Blu-ray editions several years ago. Now, Kino has

released new 4K UHD and Blu-ray versions of the film, including the original

70-minute premiere cut that hasn’t been seen since 1953. (After its premiere,

Kubrick cut about nine minutes for the theatrical release, limited as that was.

It was this 62-minute cut that has been the more familiar one to film buffs.)

Another

remarkable aspect about Fear and Desire is how ambitious it was.

Kubrick’s later, more mature works are often extremely existential in theme and

tone—they are big budget art films that challenge audiences to actually think

about what they’ve seen. Kubrick is big on ambiguity, symbolism, and metaphor

in all of his later, more well-known features. Right out of the gate, Kubrick

embarked to make an extremely non-commercial art film that deals with the

meaning of existence and the futility of war. While he would later succeed with

this kind of art house contemplative head scratcher, Fear and Desire unfortunately

comes off amateurish, pretentious, and painfully like a student film.

That

said, one who knows Kubrick’s work can see glimpses of the genius underneath

this early effort. What he was attempting is quite “Kubrickian,” and there are

moments and images that are indeed striking.

The

story is thus… A four-man platoon are fighting an unnamed war in an unnamed

country. They are lost in a forest behind enemy lines. The goal is to get back

to their side. When enemy combatants are spotted in a structure, the men decide

to strike one for the team and kill off the opposition. Weirdly, the enemy

general and his sidekick look just like the platoon’s lieutenant and private

(they’re played by the same actors). Whoa, profound! And, in typical

Kubrickian fashion, one man, another private (played by young Paul Mazursky,

who would go on to be a director of note himself) goes mad, nearly rapes a

civilian (Virginia Leith), and runs off like a banshee from hell. Will the

others make it back to “civilization?” Maybe. Maybe not. As the lieutenant

says, “We have nothing to lose but our futures.”

The

same could be applied to Stanley Kubrick’s first endeavor.

Besides

Mazursky and Leith, the other actors are Frank Silvera as the sergeant (if

anyone is the protagonist here, it’s him), Kenneth Harp as the lieutenant, and Steve

Coit as the first private. Silvera would go on to play the villain in Kubrick’s

next, also independently made, feature, Killer’s Kiss (1955). Kubrick’s

first wife, Toba, has a cameo as a fisherwoman (she and Kubrick had been high

school sweethearts). Toba also worked on the crew, but the stress of making a

first film with Stanley Kubrick destroyed their already unstable marriage.

Kubrick

had flown the cast and tiny crew from New York to California in the spring of

1951 and shot the film in the San Gabriel mountains. It then took him over a

year to raise the money to do all the post-production (mostly post-sync sound).

He submitted the 70-minute cut to the Venice Film Festival in August 1952,

where an unofficial premiere took place (he wasn’t present). Only in late 1952

did Kubrick meet the international film distributor Joseph Burstyn, perhaps the

important figure of art house cinema in America at that time. Burstyn agreed

to release the movie, and it had its official premiere in March 1953. It

received mostly negative reviews, which prompted the director to delete nine

minutes to tighten the feature. There were, however, a handful of very positive

notices from the likes of critics such as James Agee and Mark Van Doren, both

of whom recognized that there was undeniable talent buried within this strange,

unsettling movie.

Kino

Lorber’s new 2-disk release of the 4K restoration comes with a UHD disk and a

Blu-ray disk of both the 70-minute and 62-minute cuts. The longer cut is

accompanied by an audio commentary by film historian Eddy Von Mueller. The

shorter cut has an audio commentary by film historian/screenwriter Gary Gerani.

Von Mueller’s commentary is quite informative about the tortured history of the

film; however he makes several odd mistakes (he says the fisherwoman is

Kubrick’s sister, not wife; he says the star of Barry Lyndon is

“Patrick” O’Neal; and 2001: a Space Odyssey is from 1966, not 1968).

Gerani’s commentary covers much of the same ground with a different

perspective. Sadly, neither pinpoints the bits that were actually cut from the

longer version of the film. It’s up to us to figure it out (this reviewer finds

that some scenes in the first half of the movie were merely shortened… there

are no full scenes missing in the theatrical cut).

The

real treasure trove in this release is that for the first time, in the USA,

that is, we get Kubrick’s early short documentaries in high definition. Day

of the Fight (1951) and Flying Padre (1951) were only available as

bootlegs in bad quality. Only The Seafarers (1953) had been released on

home video prior. Now we have all of Kubrick’s early work on one gorgeous

release.

Kino’s

new Fear and Desire package is a must-have for Stanley Kubrick fans,

because looking past the feature’s shortcomings will reveal what would come

from the master filmmaker. It’s a fascinating step back into the auteur’s

young mind.

Click here to order from Amazon