AGENT DOWN: THE IMPROBABLE RISE AND SAD FALL ...

Cinema Retro

By Hank Reineke

The Manila International Film Festival was set to open its doors to guests on 20 January 1982. The date was nearly a year to the day that strong-man Philippine President Ferdinand E. Marco had lifted his controversial eight-year term of martial law restrictions in the country. But the lifting of the martial law brought only small relief to the majority populace. The Philippines was still racked by issues of rampant poverty, wealth inequality and unemployment. Both political and cultural observers thought it folly to stage such a gilded film event during this transitional period. The Associated Press reported the festival was to convene in a building costing some 21.5 million dollars - and still under construction. The film center, designed to house screening rooms and film laboratories, was to also serve as primary archive of Filipino cinema holdings.

The center, described as an eight-story “Parthenon-like Film Palace” was ordered to be built within the time of 170 construction days. In such rushed circumstance, a roof collapse occurred reportedly ending the lives of some fourteen construction workers. The order to erect the palatial center was given by none other than Imelda Marcos, first lady of the Philippines, often chided for her “edifice complex” excesses. Many saw this wild expenditure as sorry government decision-making considering the nation’s significant economic issues. But Marcos – appearing before the press in a pair of lovely pair of shoes, no doubt – saw it differently.

Marcos countered that a strong Filipino “film industry would help reduce Manila’s crime rate, because it would give people something to do in their leisure time.” But she was also mindful that a prestigious festival might burnish her country’s damaged image worldwide – all those pesky claims of human rights violations continued to dog the regime. Though anti-Marco forces promised to disrupt the festival should it be held, the army was prepared to protect. There was, thankfully, no violence.

On 2 February 1982, a correspondent from Variety sent in a dispatch from the inaugural staging of the twelve-day festival. The report made note that Filipino film product wasn’t often seen outside the borders of the Pacific island nation. He reasoned this was due to the selling inexperience of local producers. They had worked in isolation for so long, they simply were not familiar with the film industry’s “aggressive marketing tactics.” Two months prior to the actual staging of the event, Variety described how “reluctant” Filipino producers had been invited to a seminar – one designed to stoke their “sales offensive” skills through “showmanship” tactics. But the trade sighed that despite the well-intentioned marketing teach-in, the Filipino film industry had been too long xenophobic, their business-side interest mostly “half-hearted.”

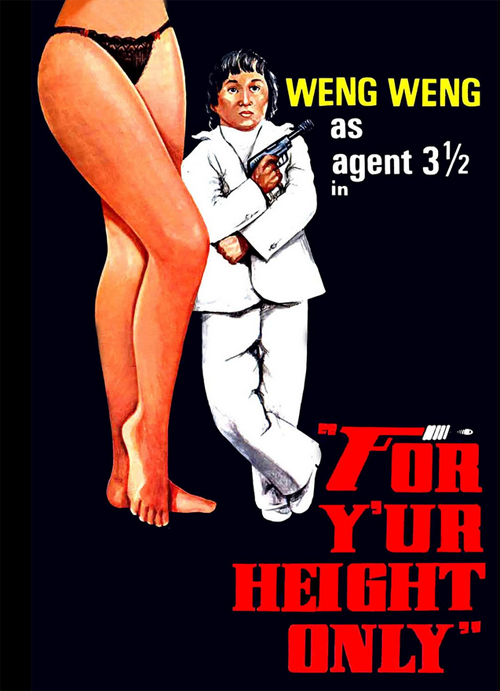

Regardless, and despite many boycotts of the Marcos-inspired event, there was a bubbling of international interest in Filipino film product. Brokers had expressed significant interest in buying distribution rights to eight of the Filipino features offered and available, the sum of those investments bringing sales of nearly a half-million dollars to local producers. Nearly 300 films had been made available to international film brokers at the event, sixty of Filipino provenance. One of the most popular Filipino films – described breathlessly as the festival’s “Top scorer by far” - was an unusual, over-the-top secret agent pastiche featuring a two-foot, nine-inch actor named Weng Weng as central hero. (Critic Alexander Walker of London’s Evening Standard would mockingly describe the diminutive Weng as “a James Bond type cut-off”). The Weng film, directed by Eddie Nicart, was mischievously titled For Y’ur Height Only, an obvious word play on the most recent James Bond screen adventure For Your Eyes Only.

I can’t say with certainty that For Y’ur Height Only played the grindhouse theaters of “The Deuce” on Manhattan’s 42nd Street, but the film would have fit in well there. It’s a spy-film fever-dream of sorts: the crack addicts and alcoholics in the grungy red seats could awake from their own narcotic-fed hallucinations and behold images on screen even wilder beyond their own madness’s. This was James-Bond-on-a-budget. A very low budget. Weng’s “Agent 00” is even introduced via an ersatz 007 gun barrel sequence, the moment heightened by the pulsing –and very familiar – opening strains of John Barry’s “James Bond Theme.”

The film itself is all spy-film formula. For Y’ur Height Only opens with the kidnapping of a scientist who holds the secret formula to a coveted “N Bomb” weapon. The syndicate behind the kidnapping is led by the mysterious “Mr. Giant” who chooses to communicate with his minions through a blinking-light, oversized facial mirror. Mr. Giant’s crime syndicate is not, all things considered, particularly political. They also dabble in street-level crimes: drugs, prostitution and theft. They’re a cabal of rogues, openly declaring, “The forces of good are our enemy and they must be exterminated.”

In reaction to the kidnapping, little-person Agent 00 (Weng, described as a “man of few words”), is summoned to report to the office of an ersatz “M.” Weng’s boss breaks down the situation before offering the agent a staggering number of gadgets to put to use while working in the field. These include a pen that “doesn’t write words,” a tiny jet-pack, and a razor-brim hat with boomerang-return capability. Of course Weng manages to dutifully employ all of these gadgets while targeting the evildoers: one minion remarks, inarguably, that Weng is “a one-an army,” another tags him as the “scourge of the secret service.”

Honestly, Weng hardly requires all the gadgetry. He parachutes from the top of a high-rise building using an ordinary bumbershoot for ballast (think Batman ’66 Penguin-style). But he more often employs his karate skills to bring down platoons of bad guys with multiple sharp kicks to their groins. Weng also appears a lot smarter than his adversaries as well: he’s always a step or two ahead of their counter-moves. In a film brimming-to-the-edges with non-stop action, Weng is constantly seen climbing above or under structures or sliding across floors to vanquish evil gunmen. The film reaches its climax when Weng engages in mano a mano fisticuffs with Mr. Giant, at the villain’s secret lair on a hidden island.

I believe it’s reasonable to say that for all of its eccentric, energetic charm, For Y’ur Height Only is completely and utterly bonkers. It’s also a very cheap looking feature film, the settings gritty and tawdry, the scripting ridiculous. The faces of the entire cast are entirely covered in the glistening sheen of South Pacific humidity and sweat. The film’s atrocious dubbing (from native Tagalog to English) – not the fault of the original filmmakers, of course – burdens the soundtrack: an additional later of aural nonsense to compliment the madness on screen. Though For Y’ur Height Only is often categorized as an “action-comedy” the original filmmakers took exception, arguing it was no such thing. In their mind, they had made a straight-up formulaic spy film, albeit one with an unusual actor in the lead role.

Following the great reaction and interest in For Y’ur Height Only at the Manila fest, there were discussions of grumbling embarrassment among Filipino artists and intellectuals in attendance. How could this amateurishly produced extravaganza of pure exploitative nonsense have bested the country’s more significantly erudite and artistic entries? But the film brokers at the festival weren’t highbrows. They were interested in buying cheap and making a few dollars off this novelty spy adventure. Kurt Palm of West Germany’s Repa-Film Productions, purchased the rights to For Yur Height Only (and two other of Weng’s films) for $60,000. Sri Lanka chipped in an additional $1500 for Height rights. Before the festival closed, the producers had sold export rights of Height to distributors in Belgium, France, Indonesia, Italy, Morocco, Nigeria and Switzerland, as well as a number of South American countries.

Soon enough, the big film markets also chose to trade. Dick Randall of Spectacular Trading (a

notable broker of low-budget, exploitation and trashy-type films) was in

attendance at the American Film Market in Los Angeles of spring ‘82. He had already secured rights to two Weng

pics ($2,500) while in Manila, including Height, for U.S.

distribution. In March Randall brought

along Weng and Height producer and Weng’s manager Peter M. Caballes to

L.A. where the film was to be screened for Randall’s U.K. partner, Sunil Shah

of Video Programme Distributors. Shah

was interested in distributing the mini-spy “epic” across British territories.

The ball was rolling. On

the day following the L.A. event, Variety would report, “The

two-and-a-half foot Weng, better known to Filipino movie fans as “Agent Double

00,” has become a hot film personality as a result of the festival.” Weng was becoming something of a hot

property. Screen International

reported that the German Kurt Palm had not only purchased the “finished pic” of

Height but already pre-optioned rights to that film’s follow-up adventure

tentatively titled Wild, Wild Weng. The latter would later be described as a “Pacific western” to be shot in

Manila. Palm also made plans to bring

Weng to Germany to promote Height directly following its release in the

American market.

In late April of 1982, Randall was in Rome readying his

distribution package of low-budget bargain films for exhibition at Cannes. Weng and Caballes were, again, at his side,

the latter talking up yet a third “Agent Double 00” pic, provisionally titled The Impossible Kid. This upcoming

film promised Weng’s inimitable infiltration of yet another “crime and kidnap

syndicate.” Caballes promised the new

film would boast a bigger budget and be shot in Los Angeles and Hong Kong. By November of 1982, Weng was now a certified

minor international film star. Screen

International bragged the twenty-two year old Weng had proven that an actor

needn’t be “a six feet tall athlete to be a successful star of kung-fu

films.”

I imagine for most fans of low-budget James Bond knock-offs, a

one-off viewing of For Y’ur Height Only should satisfy one’s

curiosities. It’s hard to imagine anyone

obsessing over the film, but that’s exactly what happened to an Australian

shopkeeper named Andrew Leavold. Leavold

was the owner/manager of Brisbane’s Trash Cinema, a video-rental outfit

specializing in cult and exploitation movies. His interest in both this spy film and Weng’s career caused him to move

forward on a seven-year Don Quixote search for the team that brought the wild

film to life. The fruit of Leavold’s

investigation is collected in his wonderfully assembled 92- minute documentary

titled In Search of Weng Weng (2007).

Leavold’s doc takes any number of crazy, serpentine twists

following arrival in the Philippines. Though he had his camera in hand, the budding documentarian had no solid

leads nor fixed starting point to begin his search. The memory of Weng Weng had been primarily

preserved in the west by VHS enthusiasts of cult action films and abetted by

the tributes of Rap and alt. rock music-artists who sang his praise. But upon his visit to Manila’s film archive,

Leavold learned that many in the Filipino art community recognized that the

pop-culture exploitation of the diminutive Weng was akin to a “national

disgrace.” Times and sensitivities had changed.

Regardless ,there was a concession that Filipino audiences

always had a taste for bizarre fare, whether carnival or cinematic in

attraction. This was certainly still true during the time of Weng’s

popularity. Leavold offers a bit of

introductory background on the state of Filipino filmmaking in the 1960s

through the 1980s, and its inclusion helps dress the stage. Prior to the establishment of Manila’s film

archive it’s estimated that nearly 80% of the country’s film product was long

gone: rotted from vinegar syndrome or lost as landfill.

Through dogmatic pursuit and several chance encounters (the

luckiest being with Edgardo Vinarao, the film editor of For Y’ur Height Only),

Leavold manages to locate and interview a number of people who claimed to know

Weng best: surviving family members, fellow actors and filmmakers. Those who knew Weng the best all thought the

world of him. He’s described alternately

as “a beautiful human being,” “a regular man in miniature,” and a person of

“great Filipino spirit.” But most chose

not to dismiss the actor’s many frailties as well. Having been born into oppressive poverty and

dwarfism, Weng was a lifelong outsider. He was “soft” and “shy” according to stuntman-turned-director

Nicart. Others saw Weng as a sad and

lonely person despite his having achieved a modicum of fame.

As a young “little person” looking to escape the grim realities

of his life, Weng (born Ernesto De La Cruz on 7 September 1957) dreamed a lot. He was fascinated with kung fu and action

movies, practicing his karate skills and gymnastic abilities to help pass

time. He was seen by some of his

colleagues as a tragic figure of sorts, a teenage boy with a “child-like

mentality” who lived “in a world of fantasy.” In 1976 Weng came to the attention of the husband and wife team of Peter

M. and Cora Ridon Caballes. He was

“adopted” (in some sense of the word as there’s a gray-area in this regard) who

saw in young Weng a marketable product worthy of exploitation.

Leavold’s doc suggests the Caballes’ exploitation of Weng was

unfortunate and perhaps harsh. On the

plus side, Weng was rescued, for a time at least, from poverty. He was even able to achieve his unlikely

dream of being an action-movie hero. He

first appeared on screen in 1976 with small roles in his native Tagalog, but

would get his first character credit (billed as the “mini-action king”) in the

Caballes production of Chop Suey Met Big Time Papa (1978). He wasn’t regarded as a great actor, but

everyone was impressed by Weng’s physical capabilities. Many recalled their surprise that Weng could

perform most of his film stunts without assistance of a stuntman-double. This was fortunate as a producer would have

been hard-pressed to find a stuntman who shared Weng’s tiny 2’ 9” frame.

Weng’s first star vehicle was as super spy Agent 00

(1981). Caballes had approached Eddie

Nicart to direct the film regardless of the latter having never helmed a

picture. As director, Nicart was strung

when he learned Weng could not speak a word of English or read a script. Sadly, Nicart is unable to recall almost

anything about that first “Agent 00” film. The movie was never released outside of the Philippines and is now

considered a lost film. But it was with For

Y’ur Height Only, and that film’s attendant publicity, that would bring

Weng his greatest fame.

The actor would go on to make an additional six films –

including that third Agent 00 adventure, The Impossible Kid (1982)

before disappearing from the screen completely. By late autumn/early winter of 1984, Weng was reduced to making a

personal appearances at retrospectives. The advertising poster for a matinee showing of For Y’ur Height Only

at a cinema in Guam read: “Weng Weng, All 40 lbs. of Him, Will be in the Lobby

of the Hafa Adai Twins and Exhibit Feats of Strength.”

One can easily argue that Leavold’s probing doc is far more

intriguing than any of the films Weng would lens. As the doc gets deeper into the search for

Weng’s whereabouts, Leavold interviews Maria “Imee” Marcos, the daughter of

Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos. She in turn

sets up a bizarre meet-and-greet between the documentarian and her mother. That meeting takes place on the occasion of

Imelda’s octogenarian-plus birthday party at her slowly decaying palace in

Batac, IIocos Norte. The film-industry

and image obsessed Imelda Marcos - with the due emotional pathos of a Norma

Desmond - recalls Weng as a hero of the “disabled and distorted,” one with an

uncanny ability to “make people happy.”

If Marcos’s camera-pleasing platitudes are slightly grating –

the scene in the doc capturing a parade of aged, well-wishing sycophants

offering an endless stream of single long-stem red roses in birthday tribute is

demonstrative of her narcissism - the doc centers on the Caballes’ as the

film’s primary villains. The docmentary

suggests the couple made more than a bit of money from Weng’s films – very

little of which would ever make its way to Weng. The couple had kept their partnership in

LILIW Films International together (he as producer, she as scriptwriter) long

after they became estranged. Business is

business. Weng, sadly, would disappear back into a world of obscurity and

near-poverty. He lived his final days in

a small home of bamboo and wood. A

stroke left him half-paralyzed and he was later found dead, of cardiac arrest,

in August of 1992. He was just shy of

age 35. The best that can be said of the

Caballes’ is they combined “their” monies to pay for Weng’s modest casket and

funeral expenses. It’s mostly a sad

story. But Weng’s Agent 00 has

improbably managed to live on in video and in the admiring hearts and psyches

of cult-cinema fans worldwide, so that’s something, I guess. Agent Down. Over and Out.

|

|