INTERVIEW BY ADRIAN SMITH

Although

born in the UK, film director Brian Trenchard-Smith will forever be associated

with the Australian cult film genre Ozploitation thanks to a number of films he

made there in the 1970s and 1980s, including such favourites as The Man From

Hong Kong (1975), Turkey Shoot (1982), BMX Bandits (1983, a

childhood favourite of mine) and Dead End Drive-In (1986), the latter

now available in UHD and Blu-ray from Umbrella Entertainment in its original

Australian release cut and the later American edit featuring an exciting array

of bonus features. To celebrate the release, I was able to speak to Brian about

the film and the fact that global audiences will now be able to see the film as

he originally intended:

BTS

- I certainly want the full Australian version to be seen by a wider public. It

never has been outside of Australia in 1986. Australian audiences did not

respond to the movie, which was badly marketed as a summer holiday youth market

romp with garish costumes and punkish costumes. You know, older people designing

a marketing campaign aimed younger people and getting it wrong. They didn’t

like the film, which was clear to me from meetings. They opened it in a Sydney

theatre which was still under construction from remodelling and some people

told me they had trouble finding which of the three theatres it was playing in.

It was damned with faint praise by Australian cinema critics who were becoming

jaundiced with the wave of Australian movies that were hitting the screen and

they felt we’re not living up to Hollywood standards, so they were sharpening

their ‘snark’. Luckily the VHS cut version that was ultimately seen by people

all over the world developed a cult following, which has led to this rediscovery.

CR

- It’s a shame that the full Australian cut didn’t make it to the UK because back

in the 1980s we loved everything Australian here, especially the daily soaps Neighbours

and Home and Away. It could have worked here.

BTS

- Yes, they said Australia was Britain with better weather, which is completely

wrong. I grew up in a part of Hampshire that seemed to be particularly

temperate except December, but Australia can have tremendous rainfall and of

course tremendous heat. I think the film would have appealed to post-Thatcher British

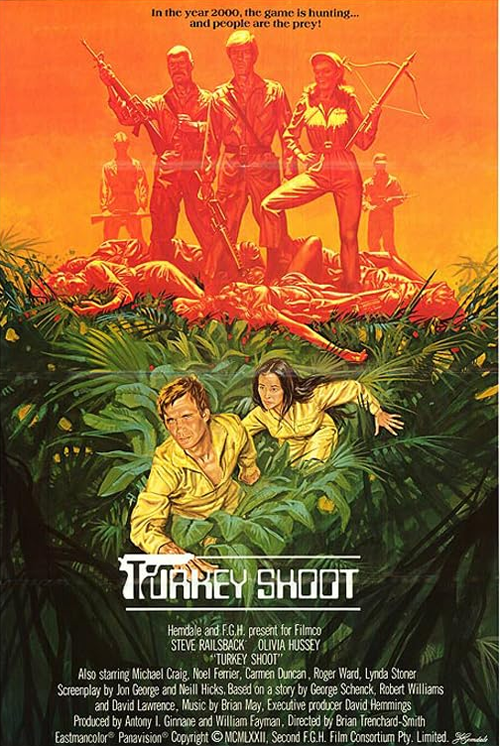

sensibility because Turkey Shoot did, even in its savagely cut form. The

British film censors hated the film but you know even with stinking reviews on

its opening day it had a queue around the block at the Warner West End at the

beginnings of a blizzard! So, there was something about Turkey Shoot that

resonated with the British public which I tried to elicit for audience to a

degree for both films.

CR

- I thought it was interesting that you shot Dead End Drive-In at the

same drive-in that you’d gone to when you were younger with your father.

BTS

- The first drive-in I ever went to was the Matraville Drive-In in Sydney. I

took my father to see Sam Peckinpah’s Major Dundee (1965), which looked great.

The way fate has it, I’m shooting in 1985 and was at that Matraville Drive-In

doing Dead End Drive-In for that three-month window before the drive-in

closed for economic reasons and became a block of flats. So, it was really kind

of great to see the film again in a drive-in recently in Portland. I had never

done that before because its release in Australia was so short, and I think there

were over 60 cars and there were some flatbed trucks with kids on with blankets

and cushions on the back, and every time there was a big stunt in there was a huge

cheer you could hear from across the drive-in.

CR

– I’d like to talk about some of the publicity materials. Can we start with the

girl in the horned bra? It’s a very striking image.

BTS

- I did not know her personally! I’ve been thinking about who she was, and I

don’t think that’s one of the stunt team. We had a lot of people who wanted to

be extras and they could have been models who were invited to bring costume

suggestions. Of course, our art department had lots of good ideas like that.

CR

- I look I kept looking all the way through the film but I couldn’t see her. She’s

very prominent in the marketing which makes sense.

BTS

- Yes, well I think there was a still photographer that day. I don’t know why I

hadn’t signalled her out for a close-up come to mention it, but maybe it was a

day in which the shooting schedule didn’t call for it, and she was not called. I

don’t know. It’s interesting the things you learn 40 years later. That’s the

interesting thing about the marketing; obviously it’s not the director who’s in

control of what the marketing people are using.

CR

– It’s the same with this chap on some of the posters, which is now on the

cover of the new Blu-ray.

BTS

- Oh yes, that’s appalling! The whole story of the release of the film in

America, as I detailed in my director’s commentary for the deleted scenes from

the American version; when they bought the film they didn’t reveal their entire

purpose which was to turn it into a summer release for the youth market as if

it was set in America, and dub it into American just as Mad Max (1979)

had been dubbed. That appalled the actors of Mad Max and Actors Equity.

When we heard about that plan, which we didn’t realize included cutting out

scenes in which there was too much Australian slang in the dialogue - I mean

what is a game of Two-up you might wonder? - the American intellect will be

baffled by that in the drive-in circuit of America. That was their thinking,

and we didn’t know there were cut scenes because the sales agent who did the

deal was kind of in the bag with them as opposed to being dedicated to our best

interests. He was dedicated to commission! And making good with his pals. We

said you can’t dub the actors. We told whole Mad Max story, and they

said, ‘Well we have the right to do anything we want under a clause of the contract,’

so we quoted Actors Equity and that the deal with our actors is that if we ever

did replace their voices with other voices they still have the right to make

one last attempt to get what the buyer wanted. That meant they would have to pay

for them to re-record their voices in American, and then you can do what you

like but at least they will not have had their voices taken away from them, which

is a terrible thing to do to an actor. The distributors didn’t like the cost of

that so they said, ‘Oh, what the hell!’ and basically halved the amount of the

release and sort of threw it away because they knew they could get their

guarantee back on the VHS sales, which I’m sure they did. We just got the

advance.

CR

- We should also talk about your short information film Hospitals Don’t Burn

Down! (1978), which has also been restored and is now available on this Blu-ray.

I know from a UK perspective that there were many of these kinds of 1970s

education and public information films that traumatised that generation.

BTS

- That was my mission! It was just a

great experience. We felt we were doing something good, and we were getting

paid something for it. The film is beautifully remastered. I guess they must

have gone back to the 16mm negative. The density of those original negatives were

really quite good.

CR

- In the article in the book which comes with the Dead End Drive-In

release there’s an original ad for Eastman Colour where you wrote about the

fact that it was the Eastman colour film that really helped you with making the

film in those lighting conditions.

BTS

- If Hammer had ever hired me to make an industrial fire safety short, this is

what I would do. I would make it into an industrial horror film. The idea was

for it to be a kind of docudrama which would faithfully reproduce life in the

hospital and then somehow integrate this fire disaster into it. That’s what I

tried to do and give it an overall consistency. We blended three separate

hospitals together, all run by the Veteran Affairs Department that had been

having problems with fires in the hospitals and commissioned this film for

about $85,000 AUD. We shot for 18 nights in three six-day weeks. I wrote the shooting script, so it edited

together easily, and it seemed to turn out well because it became shown on a

compulsory basis to every new staff member when they joined the Veteran Affairs

Hospitals. I think that spread to all the hospitals across Australia. I am told

a hospital on the north coast of New South Wales, a four-story hospital, that

had its ICU on the fourth floor, realized that non-ambulatory patients need to

be as close to the ground as possible so they moved it to the ground floor and several

months later the fourth floor caught fire and was gutted. So that could be an

example that the film saved lives. It is probably the only film I’ve made that

has! It’s one of the many reasons I’m proud of the film and I think everyone

who worked on it is proud of it.

CR-

There are some amazing fire stunts too.

BTS

– That was Grant Page and his team. They were top pyrotechnics people. This

film needed to be a great marriage between the stunt department, the fire

department, the safety department and the crew, particularly when you’re

working with children, and it all went very smoothly. It was a great experience.

A

- I would like to just talk a little bit about Grant Page as he sadly passed

away earlier this year. He had such a huge impact on your career right from the

start.

BTS

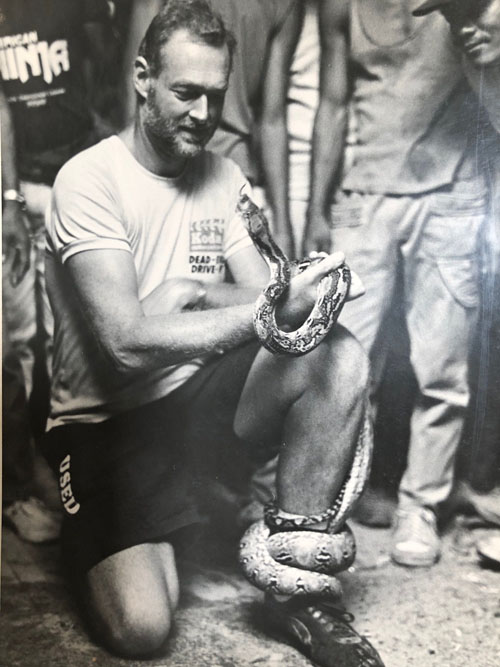

- I’d always been fascinated by stunt men, the unsung heroes of the movie

industry who do extraordinary things that make the star look good, or shock you

and make you gasp in some way ‘God, how did you do that? Who are these guys?

Gee, I’d like to be one!’ though I sensibly only dabbled at the edges. I found

a stunt man called Bob Woodham who had just come back from working in the UK on

The Guns of Navarone (1961) and You Only Live Twice (1967) and he

also did British television work. He had come to Australia at the dawn of the

Australian film industry in the beginning of 1970 so was just getting to do

stunt work in the very few Australian police procedurals. I got to know him and

decided to make a film (The Stuntmen, 1973) with him in the lead and it

won a prize at the Sydney Film Festival. I was planning to go on to make a

series but after the premier Bob unfortunately died of a heart attack. I

thought ‘Right well I’ll find the other really outstanding stunt man that I had

worked with’, who came up from Adelaide to do the rope slides on The Stuntmen.

This was Grant Page, and he had charisma in his interview. He was the perfect

person to build a series around, exploring the whole world of stunts, maybe

over four or five episodes, and that’s how Dangerfreaks (1975) was born.

I signed Grant to a five-year contract of management and managed his career for

five years and sold him to other movies for stunts including Mad Max. We

worked together on six things. I created vehicles for him like Stunt Rock

(1978). Going over to America and making Stunt Rock there allowed me to

introduce him to a producer who then took him on to be the stunt coordinator

for Death Ship (1980) and City on Fire (1979). It was Grant’s

fire stunts as exhibited in Hospitals Don’t Burn Down! that I showed that

producer and he was sold, and then they hired him to set his hair on fire as a

demented pirate in The Island (1980). Grant was a great man and I miss

him. I sent a somewhat tearful greeting to the funeral and I expressed my view

that Grant and I were pretty useful to each other at a critical period in our

respective careers. He was the perfect person to put the kind of ideas I had on

the screen and to make them work and make them practical. He was a great guy,

and he expanded my horizons and made me challenge boundaries. He forced you to

face some of your own fears. I think Grant was right - that you know your life

better if you do actually face your own fears and try to expand your boundaries.

CR

- I also wanted to ask you about physical media and what your thoughts are

about how this is helping preserve your films and find new audiences, and

whether there are any of your many films that you hope will be released on

physical media.

BTS

- Physical media is important because our screens at home are going to get

bigger and bigger, and it’s now very expensive to go to the theatre. You go for

the big spectacles, and I want people to have that communal experience, but maybe

they have to have it in their own homes, or maybe multiplexes will develop nice

comfortable, affordable little screening rooms where you get a sense of

community while watching a comedy, being amongst people who laugh or gasp but it

is a big enough screen and it’s easy to get to and it does a variety of films

that are playing. I think we’re going to have to become selective cinema shoppers,

you know if your shift starts at 12, is there a film you catch at the downtown

theaterette? I’m dreaming I suppose but I’m going back to my days where I would

go to the movies once a week, sometimes twice a week. it was always a movie theatre

you could get to if you didn’t have a car. I guess as you get old you want to

start reliving your childhood. But physical media is important. Too many films

have been lost; films of mine have been lost like For Valour, the

dramatized documentary I made in 1972 in black and white reenacting the

exploits of four Australians who won the Victoria Cross in the Vietnam War, and

it included an interview I did with then Prime Minister John Gordon, an extract

of which is somewhere in the National Film and Sound Archive. But the whole

film has been lost. A kinescope was made of it after its broadcast and given to

the Return Services League in Australia and somehow there is no record of that

print. When the negative disappears then its chances really of any lasting

survival are low. My film Britannic (2000) was shot on 35mm at Bray

Studios, the home of Hammer, a US tele-movie cashing in on Titanic (1997)

but it was shot on 35mm and then had visual effects shots dropped into black

slugs throughout the A and B checkerboarded negative, but they lost half the

negative. They lost half the checkerboard of several reels, they don’t know

where they are, so a historical drama fantasizing about what happened to

Titanic’s sistership will never be seen on a big screen in the way that it could

be because people didn’t take adequate care of materials.

CR

- So are there any films of yours which are not necessarily lost but are there

films from your career that you would like people to find again, perhaps films that

are less well known?

BTS

- I think so. My films are of curiosity because some of them have a sort of

postmodern tone to them, even back in their day. So, you look at Deathcheaters

and perhaps it is an interesting example of a sort of 1970s boy’s own

adventure. Sociologically speaking it’s interesting to deconstruct the various

elements in it, the casual way which the Vietnam War was used, of which I took

some criticism of course but to me it was just a Boy’s Own adventure film

anyway. I think a film I did called Seconds to Spare (2002) which is

basically Die Hard (1988) on a train which I did for 2.9 million AUD just

after 9/11. This caused us to lose Dolph Lundgren before the shoot and be replaced

by Antonio Sabato junior, but I’m very pleased with ‘Die Hard on a Train’,

dealing with some issues of terrorism which of course was not what anyone

really wanted to make but it had been green lit before 9/11 and it happened

during pre-production. I think it’s a good 89 minutes so you could put that

together on a double disc with another B movie such as Britannic, which

currently can only be found on YouTube. I’m thinking my work on physical media

is best packaged in good old fashioned drive-in double bills that could be put

together. I think Seconds to Spare would be one and I’m rather partial

to and Megido: Omega Code 2 because I had fun making it. It was made

before Trump and now we have we’ve had the spectacle of a populist media

demagogue gaining great power and punishing those who will not believe in him with

thunderbolts. You can take it with the right sense of humour as it gets increasingly

batty all the way through. The producers watched and did not see the humour of

it, well luckily, they missed the humour of it anyway! Voyage of Terror (1998)

is a good 18-day melodrama. It was originally called ‘The 4th Horseman’ which

means maybe the Apocalypse and pestilence and The Family Channel thought ‘Is this

an appropriate subject?’ I thought ‘Well, our audience won’t know what The Fourth

Horseman is. They’ll think it’s a racing movie or something.’ It ended up

being Voyage of Terror and it was a German/ Canadian co-production. If

you like Lindsay Wagner, if you like Horst Buchholz, if you like Michael

Ironside and Michael Sheen, and Brian Dennehy as the president, what’s not to

like? So that could be a drive-in double feature. I’d like some of those films

to at least exist on physical media. I would call upon Paramount to get Happy

Face Murders (1999) out, to get Sightings: Heartland Ghost (2002)

out. Those I think are quite good films and I’m quite proud of them. I think they

have interesting casts, and some of these films will last the test of time.

(Thankfully

Umbrella Entertainment is taking good care of Dead End Drive-In, and has

also released several other Brian Trenchard-Smith film. Brian is now on a quest

to support the next generation of filmmakers. At 600 pages long, his

autobiography Adventures in the B Movie Trade (2022) is an invaluable

resource for anyone who wants to make movies, and he is also mentoring Australian

filmmaker Casper Jean Rimbaud, who’s bizarre sci-fi conspiracy film High

Strangeness (2023) has been garnering attention at film festivals.)

Dead

End Drive-In can be ordered direct from Umbrella

Entertainment with worldwide shipping available: https://shop.umbrellaent.com.au/products/dead-end-drive-in-1986-4k-uhd-blu-ray-book-rigid-case-slipcase-poster-artcards