By

Hank Reineke

The term “legendary,” never mind what parameters one accepts

as conferment of “legend” status, is now pretty much moot. The term has so often applied to so many popular

culture figures that approbation has been rendered meaningless. Have you

visited a record store lately? If so,

you can’t help but notice racks brimming with warmed-over oeuvre albums by obscure,

passed-over and/or forgotten – and, yes, mostly dead – “legendary” artists –

singers and musicians that few have ever heard or been introduced to. Similarly, there’s now a never-ending stream

of Blu-ray box sets, all colorfully packaged and dressed, celebrating the

cinematic art of (often) grindhouse era filmmakers. These film artists too are all now believed “legends,”

even if not celebrated as such in their own time.

Personally, I’ve no problem with it. Through such revivals, I have certainly been

introduced to worthwhile music and films I would otherwise have not been

acquainted. On the other hand, there’s

plenty of “lost” music and cinema I’ve been introduced to – often at wallet-emptying

expense – that compels me to rethink the value of such blind buys. Yes, there are proverbial gold needles to be

found in sorting through this ever-heaping pop-culture haystack. But, let’s face it, there’s plenty of

splinters as well. Sorting the wheat

from the chaff is proving a never-ending, occasionally frustrating,

challenge.

To my knowledge, the combined fantastic cinema works of

filmmaker Bert I. Gordon hasn’t yet been allotted a proper box set. I wouldn’t expect one anytime soon. For starters, Gordon’s name – whether having served

as writer, director, producer, special effects artist etc. – is attached to as

many as twenty-three feature films (1954-1990). And these films were financed, bought and sold through an assortment of varying

distributors and studios. Any attempt to

equitably divvy up royalties amongst various rights-holders would make such a

project a financial non-starter and accounting nightmare.

To his oldest fans (ahem, me), Gordon’s science-fiction

and fantasy films of the 1950s and 1960s will forever be thought of as his best

and best remembered work. Though he

mostly worked as an independent and rarely had much of a budget at his disposal,

Gordon’s found a niche in his creation of fantastic cinema camera trickery and

an obsession with gigantism. From the

beginning, Gordon’s frightening titanic mutations would tower over and threaten

the natural order of things. Forest J.

Ackerman of Famous Monsters of Filmland

fame, is usually credited with giving Gordon the appropriate nickname of “Mr.

B.I.G,” wordplay of the director’s initials.

Bert I. Gordon’s career in film began modestly. He was experimenting with trick photography techniques

in his teens, later producing and directing television commercials and

industrial films in his home state of Minnesota. But he had eyes on a career in Hollywood and

in the early 1950s went west to pursue his dream. Upon arrival he wasn’t welcomed with open

arms, even by those working in the lowest-level industry positions of

Tinseltown. He was told, not

untruthfully, that Hollywood was a closed shop, where one mostly gained entry into

the business though nepotism. Unless his father was a “Hollywood mogul,” he was

advised it would be best to return to Minnesota. Gordon persevered despite such discouragement,

garnering his first industry credit as screenwriter of Tom Gries’ tantalizingly

titled Serpent Island (1954).

Unfortunately for monster movie lovers like myself, Serpent Island was a mere

run-of-the-mill jungle island adventure film – albeit one with a dash of voodoo

and a menacing boa constrictor. Things took

a brighter turn when Gordon was chosen to multi-task as director, co-producer

and co-writer of King Dinosaur (1955).

Though in their review of September 1955 Variety

deemed the film slow-moving, they also pronounced the “mild science-fiction

yarn okay for smaller double-billing.” The trade also noted that due to the movie’s absence of a star player, the

film’s potential audience draw was completely dependent on the “exploitational

value” of the King Dinosaur itself. It wasn’t a rave review, but the film’s

modest budget allowed a modest success. It was enough to establish Gordon’s reputation as a financially viable independent

filmmaker.

King

Dinosaur was the first of Gordon’s “big” monster movies, even if

that film’s titular Tyrannous Rex was simply an ordinary iguana in ill-masquerade. The film would set the course of the

director’s career for the decade or two following. An assortment of other giant monster flicks

would follow in the wake of King Dinosaur,

several now regarded as bona fide cult classics of Silver Age sci-fi. In short order, matinee audiences would be

trampled by any number of Gordon’s creations: The

Cyclops (1955) featured a radiation-birthed gigantic man, lizards and

insects; a plutonium bomb infected The

Amazing Colossal Man (1957) (who would return to wreak havoc in War of the Colossal Beast (1958). Then there were the giant grasshoppers of the

Beginning of the End (1957), the

giant arachnoid in Earth vs. the Spider

(1957), the shrunken victims of a mad puppeteer in the Attack of the Puppet People (1958) and – seamlessly slipping into

the psychedelic 1960s - the drug-induced cabal of gargantuan teenagers in Village of the Giants (1965).

Though it was these “giant monster” drive-in flicks that

would secure, nay immortalize, his

reputation as a filmmaker of gargantuan ambition, Gordon would branch out in

the 1960s as a director no longer exclusive in interest to presenting giantism. Regardless, most of these movies were still firmly

tethered to the realm of fantasy and the macabre: Tormented (1960), The Boy and

the Pirates (1960), The Magic Sword

(1962), and Picture Mommy Dead

(1966).

By the 1970s, Gordon’s career seemed to cast about. His earliest films remained almost entirely

exploitative in creation, inspired by popular titles of the times. It had always been that way. Even his gigantism films were simply

reversals of Universal-International’s The

Incredible Shrinking Man (1957). So,

when Russ Meyer’s sex-films were doing good business on modest budgets, Gordon

would follow suit… well, perhaps “un-suited” as it were. His first film of the ‘70s was How to Succeed with Sex (1970), an

X-rated soft-core sex comedy. Perhaps an

experiment with “gigantism” of a different sort? Surprisingly, New York’s Independent Film Journal thought the juvenile-minded film, “a

pleasant, if innocuous little sex flick, even though its sense of humor is a

bit retarded.” Variety thought the film worthwhile entertainment for fans of

“bouncing-breasted nudies,” suggesting “How

to Succeed with Sex has the carefree air of Bikini Beach Party

without the bikinis.”

Even the staid New

York Times proffered that Gordon’s present romp, “Parodies pornography

consciously and with a civilized wickedness.” To help promote the film, Gordon chose

to publish a “Cinemabook” tie-in

novel with the amended title of How to

Succeed with the Opposite Sex (Holloway House, 1970). The book offered, of course, no shortage of

softcore-porn photos between its covers to help sales along. (Later, in the early 1980s, Gordon would add

two additional teen sex comedies to far less critical acclaim: the Porky’s-inspired

near direct-to-video knock-offs Let’s Do

It! (1982) and The Big Bet

(1985).

When stories of Satanism were selling well, Gordon

delivered such films as Necromancy (aka

The Witching, 1970) featuring, of all

people, Orson Welles as a frustrated resurrectionist of the dead. The

production of Necromancy, under its

provisional title of The Toy Factory,

was fraught with very ugly production and legal issues. For starters, the film had reportedly gone

over 400% over budget, a frightening figure in itself. This resulted in quite a

bit of legal wrangling. Gordon

subsequently lost creative and editing control of the film, an investment

company awarded all worldwide distribution rights. It was the first sign that Gordon might be

better off not messing with the Devil. Both

Gordon’s Salem witchcraft opus The Coming

(aka Burned at the Stake, 1981) and

his Satan’s Princess (Paramount, 1990)

(the latter offered “plenty of nude

scenes [to] keep the viewer awake” as one review would note) were issued as

damage-control cable-TV and/or direct-to-video releases.

Gordon’s piggybacking on contemporary film trends continued

unabated. In 1973 when gritty,

urban-crime dramas were in vogue, Gordon jumped onboard the violent-action

bandwagon with The Mad Bomber (aka The Police Connection, 1972). Gordon seemed to have lost his interest in

the sort of fantastic cinema that made him famous to a generation of Monster

Kids. Or was it that the audience itself

had lost interest? “I don’t believe the

majority of people go to the theatre anymore for entertainment,” Gordon offered

this bit of unfortunate psycho-hokum to Variety

in the spring of 1973. “People in the

old days used to go to a theatre to see a film for fantasy. I believe that people now live a great

percentage of their lives vicariously. I

therefore believe it’s healthy for these people to live-out in a theatre such

fantasies to be a killer or rapist – at least it’s a controlled situation where

they’re not threatening anyone. If the

people didn’t have this release, they would become a threat to society.” He concluded this was not so different than

how horror pictures, including his own, presumably, had earlier served as “a

healthy release for young people.”

Regardless of his wonky psychological musings, it’s

Gordon’s catalog of “fantastic” films that live on. Over the last several years Kino Lorber has released

a number of Gordon’s films on Blu-ray, a trio arguably thought the best of the

director’s 1960’s output: Picture Mommy

Dead, The Magic Sword and Village of

the Giants. Over the last several

years Kino has taken up the torch of MGM’s magnificent Midnight Movies DVD

library Y2K series of classic – and, on occasion, not so classic – “drive-in”

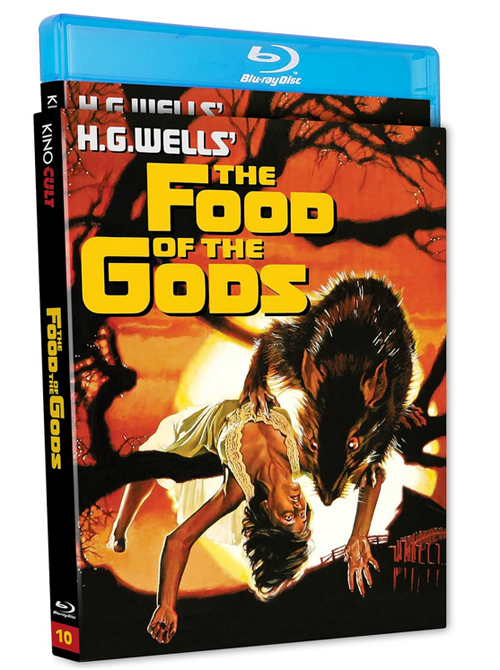

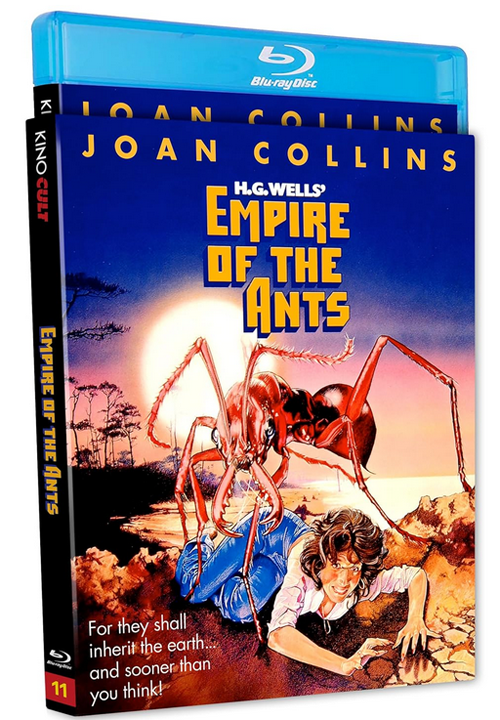

film sets. This summer Kino now offers

two of the best – and best recalled – of Gordon’s films of the 1970s in stunning

Blu ray transfers: his adaptation of two of H.G. Wells’ sci-fi classics Food of the Gods (1976) and Empire of the Ants (1977).

Gordon would wear many hats on the production of Food of the Gods: he would serve as

director, producer, visual effects and screenwriter. His scenario mostly abandons Well’s more erudite

musings on the unintended consequences of human scientific and ecological misuse. (In Gordon’s defense, his film scenario is credited

as having only been “based upon a portion” of Wells’s novel). Gordon also chose to move the original story

from England to the wilds on British Columbia. It was on a reported budget of $900,000, that location shooting

commenced on November 10, 1975 and continued for thirty-two days on Bowen

Island off the Vancouver coast. It was a

challenging time of year to shoot in BC, and the crew was plagued by passing episodes

of freezing temperatures, mild earthquakes, sudden squalls and rainstorms. The film’s photography adequately captures

the atmospheric dreariness of the season: cloudy mists, dank woods, dampness

and gray skies. Special effects

production would primarily take place in Montreal that same November.

The film’s story revolves around a desolate cabin and

modest tract of farmland where an aging couple, the Skinners, reside. A mysterious spring of a milky white fluid

has been bubbling from beneath the soil on the couple’s property. The Skinner’s (John McLiam and Ida Lupino)

have discovered that mixing the fluid with ordinary chicken feed has alarmingly

allowed members of the roost to grow to gargantuan size. Believing the strange spring a gift from God,

the religious couple contact food-industry executive Jack Bensington (Ralph

Meeker), to capitalize and perhaps financially benefit from their discovery. Unfortunately for all involved, other animal

and insect species have also been drinking from the run-off of the milky food

source.

The result is the woodlands have run amuck with roaming

teams of angry and carnivorous giant rats, wasps, grub worms, and

chickens. The Skinner’s retirement plan

has not rolled out as easily as they might have hoped. Things take a turn for the worse when folks

visiting the island are being viciously mauled by the giant rodents and other mutated

species. Like most religious zealots,

Mrs. Skinner tries to have it both ways, accepting recent developments as her

faith allows – that is it’s not her fault. She initially accepts the powers of the milky spring as a “gift from God.”

Following a few deadly attacks, she accepts what’s going on as a form of punishment

from the very same deity, an obvious result of their sins “against nature.”

The film’s dubious “hero,” Morgan (Marjoe Gortner) is a

pro football player and amateur sportsman who reluctantly gets sucked into the melee

when, near the film’s beginning, a hunting friend is attacked and killed by a

squadron of angry, giant wasps. In

retrospect, Morgan is someone who should not have been looked upon to take

charge and bark out orders. He’s pretty

much responsible for the untimely ends of several characters due to hot-headed,

impulsive decision making. There are

other tangential characters written into the script, but one suspects they’re

mostly there as victim-fodder. Though others

suggest otherwise, I think Gordon’s special effects are pretty good, all-in-all,

for their time. Certainly the rodent

attacks are viciously grim and disturbing. It must be said that equally disturbing are real-life images of rodents

being shot and bloodied close-up. Though

PETA wouldn’t form until 1980, there’s no doubt members would have been protested

outside any cinema where Food of the Gods

was being screened.

Though Gordon’s two 1970s eco-horrors remain favorites of

fan-cultists, critics mostly offered negative or begrudging reviews of Food of the Gods. Variety

coldly dismissed Gordon’s latest adventure of gigantism as “a tax shelter pic,”

“a good idea shot down by bad story.” They also decried Gordon’s scripting as “atrocious,” a charge – to be

sure - often levied against his abilities as screenwriter. To be certain, some of the dialogue is

cringe-worthy. The suggestion by

Meeker’s assistant Lorna (Pamela Franklin) that she wants to “make love” to Morgan

when an army of giant rats are poised to descend is particularly and groaningly

ill-timed. Screen International described Food

of the Gods as “engaging nonsense acted with suitable solemnity by a cast

that nobly keeps its collective gravity even when the situations and dialogue

are overly contrived and ridiculous.” Box Office also noted that Gordon’s

characters as written, “tend to be less than believable.” These criticisms are not unfair.

Though the bad reviews continued unabated, executive

producer Samuel J. Arkoff had plenty of reasons to ignore them and celebrate. Food of

the Gods proved to be one of A.I.P.’s biggest money-generating pictures of

1976. So,the production of a more-of-the-same sort of picture was

soon green-lighted. For his follow-up to

Food of the Gods, Gordon would again

plumb the rights-free work of H.G. Wells. This screenplay, by Jack Turley (from a “screen story” of Gordon’s), for

Empire of the Ants is very loosely based on a dystopian short

story by H.G. Wells first published in December 1905.

Gordon – who serves here as producer-director-and visual

effects coordinator - thought Wells’ brigade of swarming ants less exciting

than an army of (of course) super-sized

ants. It was one of many amendments

Gordon and Turley would make to Well’s more cerebral science-based material. Gordon also chose to move Wells’ scenario

from the Amazon basin of South America to the shores of Florida –though he

first needed to hard-sell A.I.P.’s budget-conscious Sam Arkoff that shooting in

the Sunshine State was both practical and

economical. Cameras would first roll on

November 22, 1976 in Palm Beach though most of the island footage was shot near

Lake Okeechobee in the Everglades.

This time out, we watch as barrels of radioactive waste

materials are dumped into the sea off the coast of a Floridian island called

Dreamland Shore. The island is, to put

it mildly, a mostly storm wrecked, desolate stretch of sand, jungle and

swampland. This doesn’t deter such scheming

realtors as Marilyn Fryser (Joan Collins, in her usual ice-cold bitch persona)

and Dan (Edward Power) of ferrying potential rubes to the island. The realtors hope to interest them to purchase

or invest in a waterfront parcel prior to the construction of a sketchily

promised resort still to be built. Robert Lansing, in his role of the non-dashing, stoic and grumpy

ferryboat captain Dan Stokely, serves as an anti-hero of sorts, but even he’s

tough to warm to.

No realty deals are actually made. This turns out to be a wise decision since if

there ever was a situation of “buyer beware,” this is it. The group discovers

upon arrival that the island has been overrun by an army of hostile, giant mutant

ants. Worse yet, the creatures are picking off this recent gaggle of investor-buyers

at an alarming rate. In all honesty, I can’t

say I grieved when most of the realtors and/or clients are gruesomely

dispatched. The characters Gordon creates

are a pretty unlikable bunch… with the exception of a doddering, elderly couple

whose dreams of a happy retirement also don’t go as hoped. Sadly, Gordons’ on-screen characters are

rarely warmly scripted or half-developed to satisfaction, to say the least.

The first twenty-minutes or so of the film is sacrificed

to exposition. We’re first given a dull,

voice-over primer on the scientific background and practices of ants and their

colonies. This is followed by a parade

introduction of the film’s main players, nearly all written as folks with lives

riddled with personal issues: neuroses, failed romances, poor life-choices and

petty grievances. Gordon’s visual

effects are again generally effective given budget limitations, but his

photographic tricks are still moored in techniques of the 1950s. His use of miniatures and inter-cutting

images of actual live ants with disguising shaky-camera images of giant mutant

ants are dated and incredulous - but forgivable. Forgivable, as the film does manage to deliver

on its “big monster” promise, the script even introducing an interesting twist

or two near the film’s end. One can’t

argue with success, and Empire of the

Ants managed to bring in a healthy 2.5 million at the U.S. box office, most

critics thinking it superior to Food of

the Gods.

In

2010, Gordon self-published his The Amazing Colossal Worlds of Mr. B.I.G.: An Autobiographical Journey. It was a book highly anticipated by fans of

1950’/60s’ sci-fi films. Sadly, Gordon’s admirers were, alas, in for a bit of a

literary letdown after reading. Though the

book sprinkled in an occasional interesting anecdote or two, it was also blighted

by factual inaccuracies and bloated cut-and-paste filmography info. His fans certainly expected more and internet

chatter and reviews regarding the book were respectful but circumspect. It was a mostly disappointing memoir, as

months prior to his book’s publication, Gordon hedged on answering any questions

regarding his oeuvre to genre

magazine writers. Instead, he promised fans

that all would soon be revealed in the forthcoming autobiography. But that mostly wasn’t the case.

Gordon partly exonerates himself in his audio

commentaries offered as special features on both of these new Kino Lorber sets. That said, you’ll probably glean a lot more

informative content from the commentaries of Lee Gambin (who sadly passed away prior

to this set’s release) and John Harrison on the Food of the Gods set and that of David Del Valle and Michael

Varrati on the Empire of the Ants

set. Their contributions are rounded out

by some interesting on location remembrances of seventh-billed Food of the Gods actress Belinda Balaski. (The actress plays “Rita,” a pregnant woman

whose Winnebago has broken down not far from the Skinner cabin). Both releases also include the original

theatrical trailers of each film as well as removable English subtitles. The films look great with just enough grain

present to stamp each Movielab color feature as a distinct product of the

1970s. Both films are presented in an

aspect ratio of 1.85:1 1920 x 1080P and DTS audio. Food of

the Gods is the #10, Empire of the

Ants the #11 issue of the company’s Kino Cult series. Four of the films in the Cult series are

offered in 4K, though the two discussed here are only available as Blu- ray

releases. Both Food of the Gods and Empire

of the Ants are “B.I.G.” hits in my home. Perhaps they’ll be in yours as well.

Click here to order "Food of the Gods" on Amazon

Click here to order "Empire of the Ants" from Amazon