By

Hank Reineke

Few would have argument with Shakespeare’s belief that

all the world’s a stage, but for some folks the stage was simply not

enough. It certainly wasn’t for Edgar

Lansbury, the younger brother of actress Angela Lansbury. Edgar Lansbury was a significant figure of

New York City theatre, having produced a number of Broadway dramas and musicals

from 1954 on. One of his earliest collaborators

was a renaissance man of New York’s theatre scene, Joseph Beruh. Beruh and Lansbury became acquainted when the

former was cast in the Lansbury’s 1954 production of Brecht and Weill’s Threepenny Opera at Greenwich Village’s

Lucille Lortel Theatre.

Beruh would subsequently and dependably multitask in all

of Lansbury’s productions circa 1957-1970. Beruh wore many different hats during this period: as performer, General

Manager, Assistant Stage Manager and Production Assistant. In 1972, Beruh seemingly was given his

due. He and Lansbury were now co-producing

shows in midtown Manhattan as full partners, first with playwright Paul

Foster’s Elizabeth I at Manhattan’s

Lyceum and later with the Stephen Schwartz/Bob Randall musical The Magic Show at the Cort.

Prior to their partnership, Lansbury alone chose to test

openings into the film industry. His interest

was practical and, in the words of one newspaper columnist, due to the

“precarious state of Broadway [which] almost forces theatre producers to

diversify.” The resulting film, The Subject Was Roses (1968), would

feature Broadway actor Jack Albertson reprising his stage role in Lansbury’s

stage production. The actor was cast alongside

Patricia Neal, the latter valiantly struggling back from suffering a series of

debilitating strokes. The film itself was

playwright Frank D. Gilroy’s cinematic adaptation of his own successful drama. As a

theatrical drama, The Subject Was Roses

ran for nearly two years and 832 performances from May 1964 through May 1966,

successfully staged at several New York City venues. Though Lansbury’s film

version performed only modestly well at the movie box office, both Neal and

Albertson were honored by the Academy, each nominated, respectively, in the Best

Actress in a Leading Role and Best Actor in a Supporting Role categories.

Lansbury’s second foray into feature film production

would be with new partner Joseph Beruh acting as co-producer. The picture was James Ivory’s The Wild Party (1975), a dramatic comedy

set in the Roaring ‘20s. The Wild Party, which featured James

Coco and Raquel Welch, also did not tally up as a successful domestic

release. This was in part, no doubt, due

to the fact the MGM film did not enjoy a widespread general release in the U.S. Looking to broker an overseas deal to

capitalize on their disappointing investment, the producers brought the film to

the film festival at Cannes that same year.

It was at Cannes that Lansbury and Beruh discovered the

foreign market’s seemingly insatiable interest in acquiring low-budget horror

films for distribution. A friend and

colleague happened to be in Cannes that very same year, to showcase his newest

horror picture already raking in bushels of cash. As Beruh recalled, this friend “told us how

well it did it Europe and how much money it was making.” So the two prospective producers graciously attended

a screening of their friend’s fright pic cash-cow. They discovered, to Beruh’s surprise, that

their friend’s film “was terrible. We

decided we could make a horror film far better than that.”

The seed idea of producing a low-budget horror was appealing

to them. It certainly triggered their

safe-bet business acumen, and seemed reasonable to invest in an inexpensive horror

pic upon their return home. Should their

horror picture perform poorly in the States, there was still the safeguard of

selling and distributing the pic oversea to offset any domestic loss. Their decision to move forward with their

plan was wise and prudent. Even before their

very first horror pic, Squirm (1976),

was set to unleash at cinemas and drive-ins across the U.S., foreign market pre-sales

had already guaranteed they’d recoup all of their investment.

The question was where to start? “It’s easier said than done to find a good

script,” Lansbury explained to one entertainment journalist. In a separate interview with a news writer

from Rochester, New York’s Democrat and

Chronicle, Lansbury more fully explained, “There aren’t many good writers,

especially in this genre. Too many of

the scripts are actually tongue-in-cheek comments on horror films […]. We wanted a real story of terror and

suspense.” “We looked at about forty [scripts]

in the next few weeks and finally found Jeff Lieberman,” he offered to columnist

Joan E. Vadeboncoeur. There was a major

sticking point, however: Lieberman would “sell the script only on the condition

that he’d direct the project.

“It was a big risk, but a good one,” Lansbury would offer

in retrospect. Lieberman was an unknown,

but had been “remarkably eloquent speaking about his project and he had done

editing for an art film company.” Beruh,

for his part, also was intrigued by the script for Squirm, not interested in financing a Vincent Price Gothic-type of

horror film. Beruh too was looking to

find a script offering a scenario fresh and original. As he remembered it, the sorting through

piles of prospective scripts was challenging and tiring. “We were sitting around the office one day,”

he told newsman Gene Grey, “wondering why nobody had written a good horror

film.” That changed when a “long-haired

kid, Jeff Lieberman” came in to pitch his screenplay. “We liked his script a lot,” Beruh confessed,

“but there was a catch. He wouldn’t sell

it unless he got the chance to direct it.”

As Lieberman recalls, the film producer Edward R.

Pressman – who had recently oversaw production of Brian De Palma’s horror-rock

musical Phantom of the Paradise

(1974) was also interested in Squirm. But it was Lansbury and Beruh who moved more

aggressively to seal a deal. The two

executive producers immediately turned to Samuel Z. Arkoff’s

American-International Pictures – the distributor of their ill-fated The Wild Party – for advice and financing. This was a prudent move as Arkoff’s A.I.P.

had a long, storied history of giving young, untested talent a chance of entry

into the film industry. To be sure, Arkoff

wasn’t a particularly generous, benevolent benefactor in this regard. But he was certainly well aware that young, aspiring

talent would work the hardest – and, perhaps more importantly - for the least

amount of financial recompense.

Jeff Lieberman was a self-confessed admirer of the films

of Alfred Hitchcock and, according to Lansbury, closely “modeled his script

after that master.” (Upon the film’s release, several critics noted the

similarities of Lieberman’s film to Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963). Though Lieberman’s credentials were slim, he was

no neophyte nor amateur. He had already

incorporated his own business, Jeff Lieberman Associates, writing and producing

a number of documentaries titled “The Art of Film,” distributing the series

through college film studies programs. He had also written and directed a twenty-minute long satirical short

titled The Ringer (1972), which

garnered prizes at film festivals in Atlanta, Chicago and Washington D.C.

In two of this releases Special Features included in this

set, “Digging In: The Making of Squirm”

and “Eureka! A Tour of Locations with Jeff Lieberman” the writer/director

reminisces the first draft of the film script was initially written –

literally, on yellow-legal pad sheets – circa 1973 when he was all of 25 or 26

years old. Unable to type, his wife was

consigned to that duty, thinking her husband’s scenario as imagined was “the

worse I ever heard.” Though she would be

proven wrong, the very idea of a sea of monstrous worms surfacing from the soil

to feed on human flesh had been inspired by an unusual set of circumstances.

Lieberman’s science-minded older brother had read in an

issue of the scouting Boy’s Life

magazine that if one transmitted electric impulses (via a model train

transformer) through soil, this would cause earth worms to be drawn to the

surface. The curious brothers would

experiment to that effect, the then thirteen/fourteen year old future filmmaker

learning such trails of electrification to be true. A decade later - and having grown up in the

era Timothy Leary still-legal LSD experimentations - Lieberman chose to

dose. The experience with acid triggered

memories of his earlier backyard scientific experiments - and hallucinations of

a terrifying worm onslaught. All grist

for the writer’s mill…

Lieberman’s story (as filmed) is set in the backwoods

town of Fly Creek, Georgia, a remote, mostly desolate tourist destination for

antique hounds and fishermen. A sassy,

red-haired local gal, Geraldine “Geri” Sanders (Patricia Pearcy) lives on the

outskirts of town with her sister Alma (Fran Higgins) and widowed mother Naomi

(Jean Sullivan). The Sanders live

astride a Worm Farm operated by the crusty Willie Grimes (Carl Dagenhart) and

his simpleton son Roger (R.A. Dow). Geri

has been mooning for a New York City boy, Mick (Don Scardino) whom she met

sometime back and invited to visit under the guise of helping him locate

antiques. Mick’s visit does not sit well

with jealous Roger who too has been holding a torch for Geri.

There’s lots of exposition in the film’s first reel, and

we meet a number of locals – including Sheriff Reston (Peter MacLean) who

appears to have little patience for city-slicker Mick. The unfriendly townsfolk are “suspicious of

strangers,” as per Geri. It doesn’t help

that Mick’s visit coincides with a local emergency. A powerful storm has swept through Fly Creek

flooding the town and making roads impassable. The town has been left with no power nor telephone capacities. The violent storm has in fact knocked over a

number of power towers, cascading live wires sending 300,000 volts of

electricity into the muddy soil.

Regardless, Geri drives Mick over to Aaron Beardsley’s

antique shop for a look, but the old man is oddly nowhere to be found. They do find a skeleton on Beardsley’s

property that might, or might not, be him. It’s around this time that Mick transforms into one of the Hardy Boys,

trying to unravel the Beardsley mystery, even breaking into a medical office to

examine the old man’s dental records. Mick eventually deduces that it was the sudden conduction of fallen

electric wires with “soaking mud” that has summoned 250,000 flesh-eating worms,

nightly, to feast on the townspeople. That’s the story at its most basic anyway. There’s a subplot or two woven into the

storyline as well, but the rest of the film leaves viewers to contemplate who

will or who will not survive this awful “night of crawling terror.”

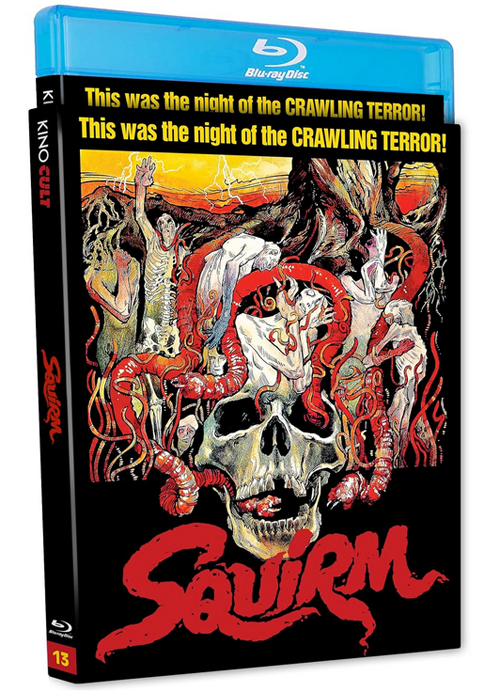

“This was the night of crawling terror” was the

promotional tag of the film’s one-sheet poster. The producers were initially unhappy that the film was being marketed as

simply another “animal fright film,” a genre now in vogue, especially in

following the runaway success of Spielberg’s Jaws. Beruh told journalist

Carol Wilson Utley he thought Squirm

was more Hitchcock in its styling and more frightful than Jaws. After all, Beruh

reasoned, “sharks are just in the ocean” and, should one choose, absolutely avoidable. On the other hand, “worms are

everywhere.” Beruh was also put off by

the horrific poster art commissioned for the film, a garish, colorful image of

worms and corpses and tree trunks emanating from a grimacing, evil skull. “This is not just another horror movie,” Beruh

defended. “It’s also a good movie – a

well-made movie. But to insure its

success they want to get all the real hardcore horror fans out.”

Squirm was

given a budget of some $400,000 with photography to commence in November of

1975. Lieberman’s original script set

the film in New England, amidst a “Lovecraft type” of fishing village. The problem was that the New England climate

was thought too inhospitable for a November filming. There was one lifeline. The state of Georgia was slowly becoming a

hub of film production, Georgia’s Department of Community Development happy to

welcome prospective film projects to the area. One of the more recent and successful projects launched in the Peach

State was United Artist’s Burt Reynolds’s action pic Gator (1976), that film’s box office success having sparked

interest in Georgia’s low-cost hospitality.

The one drawback in this dramatic change of scenery was

that many of the New York area actors originally considered for roles were now redundant. The geographic change to slangy southern dictions

would cause both re-scripting and the casting of local talent (and even a

number of non-actors) for roles in the production. One budding actress anxious to be cast was twenty-one

year old Kim Basinger, who even agreed to taking on the role of Geri Sanders

even though it called for a nude scene. Lieberman retrospectively sighs his decision to pass on casting Basinger

was likely an opportunity lost for fanboys everywhere. The leading players of the cast were proven

professionals gleaned from New York, Massachusetts and Texas.

The primary location shooting of Squirm was to commence in the seacoast town of Wentworth and areas

near Savannah. Principal photography

began in Savannah on Monday, 10 November. Serving as executive producers (George Manasse would produce), Lansbury

and Beruh would form a limited partnership, appropriately named “The Squirm

Company,” to oversee production of the film. Box Office would report the

film was in the can by early January of 1976. That said, things got off to a rough start. Lieberman recalls that due to a generator having

exploded on the first day of filming, as director he had already fallen behind

the agreed upon production schedule by the third day of shooting.

This nearly resulted of his dismissal, New York executives

angry of not getting any of the promised rushes to view as demanded. Lieberman recollects it was the film’s

cinematographer, Joseph Mangine, who saved him, advising him to abandon his

idea of shooting the film in sequential sequence and instead concentrating on getting

as much footage in the can as quick set-ups and breakdowns allowed. Within days of going this route, the crew was

back on schedule. The autumn weather –

even that of southern Georgia – was alternately sunny then grey, gloomy and

overcast. Leading actor Don Scardino

(“Mick”), who would soon work with Lansbury and Beruh on the Broadway stage production

of Godspell, thought the mixed weather

and inclusion of local talent brought the film, “a strange, truthful

ambiance.”

For the film’s exciting conclusion, some 250,000 worms

were brought in to complete the final “big” sequence. This required the assistance of a local Boy

Scout troop “to assist in the handling” of the worms. In fact, the scouts were buried strategically

and hidden under mounds of worms – real and of rubber – and tasked to bounce beneath

as to create the “percolating” mass we see on-screen. For their trouble, each Scout was reportedly promised

a Merit Badge. It must be said that

Lieberman’s direction is effective in bringing to the film a sense of creepy,

growing tension. The micro close-up cut

in shots of real-life fanged worms are certainly disturbing. There is a bit of gore, but not as much as

one might expect from a film of this type. Lieberman would tell the Rochester Democrat

and Chronicle, “My violence is implied. I believe a filmmaker can never present on screen as much violence as an

audience’s own mind can imagine.”

Variety reported

that with editing of Squirm near

completion, distributor previews would begin in New York City the week of 12

April, with secondary screenings to follow in Los Angeles the week of 19 April. In June, Lansbury and Beruh brought the film

to Cannes, choosing to “pack the four […] screenings with non-pro locals, thus

giving potential buyers a taste of how the general public would react to the

film.” This gambit paid off and by the festival’s end they had made a deal with

no fewer than sixteen territories at a guarantee of a half-million dollars. To the confusion on many industry watchers, the

shrewd Arkoff instructed the producers to forego any “terrific” upfront and

advance foreign deals and instead choose what initially appeared to be mere

“reasonable” percentage offerings. This percentage

decision was a wise one as the film performed exceptionally well in the United

Kingdom and other European markets.

Closer to home, the filmmakers were looking for an open

spot on the future release roster of a major Hollywood studio. They thought they saw opportunity for

Columbia Pictures to bring their modest horror-meller to theatres

nationwide. The publicity department at

Columbia thought Squirm as a great investment

and a cash-generating exploitable. The

only thing required was the blessing of Columbia Pictures president David

Begelman. The deal might have happened had

it not been for the intervention of Begelman’s wife. Begelman’s significant other happened to

attend the Squirm screening with him,

mortified and aghast at the Glycera-inspired carnage unfolding before her

eyes. She convinced him not to have

anything to do with what she thought cinematic trash. Her advice proved ill-informed and costly. The

film was ultimately picked up by Paramount.

If Paramount was a big winner, so was Lieberman, A.I.P., Lansbury

and Beruh. The two producers quickly signed

Lieberman to a fresh contract to deliver a second sci-fi thriller of his own

scripting, another LSD-inspired fever-dream titled Blue Sunshine. Following the

test-market of Squirm in Buffalo, New

York, Paramount released the film, to the excitement of horror movie devotees in

the several regional markets, on Wednesday 14 July 1976.

The reviews of Squirm

were mixed, and Lieberman conceded, with honesty, that while his film performed

particularly well in some U.S. markets, “it did poorly in other places around

the country.” It was an original film, if one displaying its low budget. Though Variety

noted “an admirable earnestness to the effort,” the “creepy special effects” of

Squirm were “offset by clumsy and

amateurish low-budget location production.” Box Office was more effusive

in praise, offering despite “cheap production values,” Lieberman’s film managed

to deliver, “a tight little thriller that should be one of the year’s top

horror pix.”

By mid-August, and only a month into release, Squirm had already racked up a domestic

box office of $642,200, placing 8th in the Top 50 Grossing Pictures

(The Exorcist topping that chart even

in its sixty-fourth week of release). By

mid-September the picture dropped to number twenty in the rankings but

continued to bring in dollars totaling $815,850. When the company’s Squirm and Food of the Gods

made its way to England’s shores in autumn, the trades dubbed the pair, “two of

the highest grossing films American International has had in England in years.”

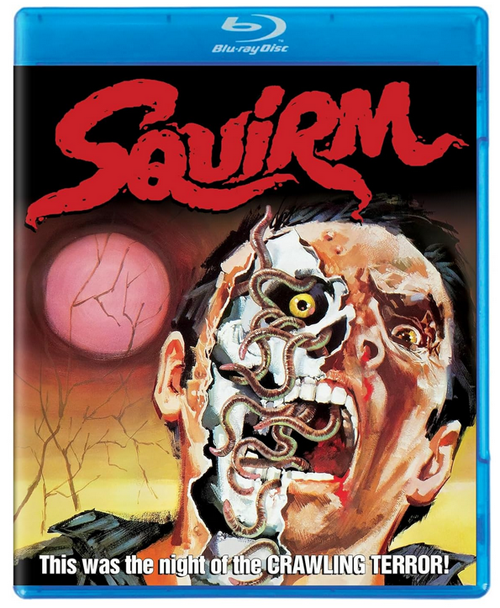

This Kino Cult Classic Blu-ray edition of Squirm is offered in an aspect ratio of

1.85:1 in 1920 x 1080p and dts audio. It’s

another low-budget, gritty 1970’s film in glorious Movielab color. Along with the above mentioned special

features docs “Digging In: The Making of Squirm”

and “Eureka! A Tour of Locations with Jeff Lieberman,” the set also includes

two separate commentary tracks, one by Lieberman, the second by two Aussie film

historians, the late Lee Gambin and John Harrison. Lieberman’s track offers much of the same

musings he shares in the two documentaries included (both of which have been

sourced from Scream Factory’s 2014 Blu- ray release of the film), though tales

are occasionally offered here in more detail.

Gambin and Harrison are obvious enthusiastic fans of

Lieberman’s film, worms and all, and competently fill in all sorts of

production information and statistics along the way, even offering some insight

on the director’s Blue Sunshine

follow-up. It’s also worthy to note that

Gambin had the opportunity to interview late executive producer Lansbury

(1930-2024) for an earlier project. This

enabled him to share some of those remembrances of Squirm in his own commentary. The set rounds off with original television

and spots for Squirm, as well as the

film’s original trailers – and a half-dozen or so of other Kino horror

releases. I’d suggest Squirm is, in some manner of speaking,

less an “eco-horror” as promoted, but more of a Frankenstein pic due to

electric charges having animated the film’s “monsters.” But that’s opening another can of worms

entirely.

Click here to order from Amazon