By Lee Pfeiffer

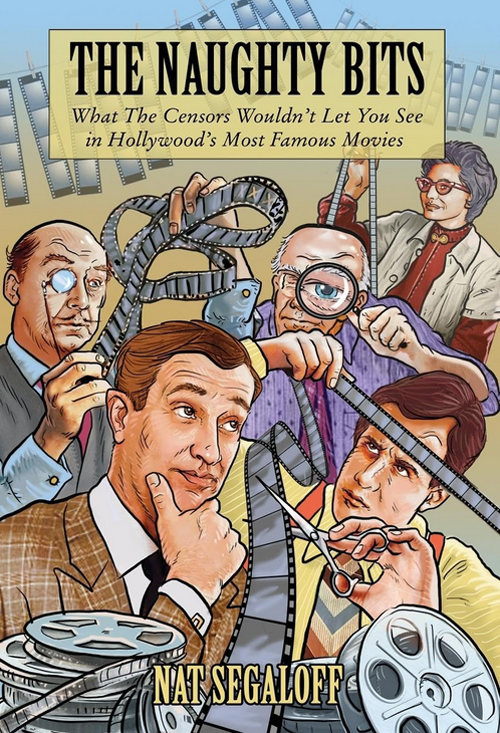

Author Nat Segaloff can write excellent film-related books faster than I can read them. Segaloff is veteran of the movie industry and worked as a marketing and publicity executive for such high profile films as "The Exorcist" and "The Towering Inferno". (Yes, he's written books about both.) His latest work is titled "The Naughty Bits: What the Censors Wouldn't Let You See in Hollywood's Most Famous Movies". It's a look at the history of censorship in the American film industry. The industry did not want to answer to a government-run censorship office so it was decided that the movie studios would police themselves by answering to a bureau they created themselves. It would be referred to by numerous official names during the course of the decades that followed but it was commonly referred to as the Production Code Office. Ironically, instead of being fairly liberal about the content of motion pictures, the office would prove to as stringent as many had feared, especially when the notorious Will Hays was appointed head of the bureau in the late 1920s. Hays, a former Postmaster General of the United States without any experience in the film industry, came to believe he needed another strongman to assist him. Thus, in 1934 he promoted one Joseph Breen to the position as the nominal head of the Production Code office, leaving him to do most of the day-to-day dirty work. The studios would soon suffer the consequences of the decision. Segaloff's book goes through this entire period in great detail but ensuring it makes for a breezy read. The most consequential aspect of the new rules that were introduced was that every motion picture had to be submitted for approval in order to get the Production Code office's coveted "Seal of Approval". Although there were no laws mandating that films needed to obtain this, in reality, it was virtually impossible for studios to get major distribution for any film if it had not had the Seal bequeathed upon.The book illustrates that the Production Code Office wasn't the only group of uptight people studios had to contend with. Even if a film received the Seal and was put into general release, Catholic and Protestant churches wielded great influence over what appeared on movie screens. Additionally, some individual American states had their own censorship boards that took it upon themselves to carve up films before they were publicly exhibited.

Segaloff consulted a virtual library of old files pertaining to the Code and is able to recreate the draconian power that the Production Code office brought to the making of every type of movie. Breen was a conservative blue-nose when it came to all sorts of objections. This began in the formative stages of a movie, with the studio submitting their final script for approval. Inevitably, Breen and his henchmen would find countless objections in even the most mundane plots and bits of dialogue. Woody Allen once said "Sex is only dirty if you're doing it right." However, the Code officials were that breed of men who still exist today: they were afraid that somewhere, somehow, somebody was enjoying sexual activity. Breen and his cohorts objected to almost any insinuation of sex, especially the illicit kind. Female characters bore the brunt of the objections, as any woman who seemed to initiate or enjoy lovemaking was deemed to be too tawdry for adult audiences to cope with. The self-imposed guardians of American morality therefore demanded significant changes to virtually every script sent to them. The result was the watering down of eroticism at every level. Clever studio executives often objected to these demands and sometimes they won the case, but more often than not they had to comply, 'lest they would not receive the Seal. This meant that for decades American movies would suffer from being infantilized. Cursing was forbidden until MGM managed to get permission for Clark Gable to memorably say "Frankly, my dear, I don't give a damn"- and that took until 1939. The use of alcohol was also subjected to tight restrictions on the big screen.

Segaloff chooses an abundance of famous movies and provides a page or two on each to describe the ordeals that studio executives had to go through in order to release a film that resembled what they had envisioned. The list of objections naturally mostly affected such steamy films as "The Apartment", "Hud", "A Streetcar Named Desire", "Psycho" and "Sunset Boulevard". However, Segaloff also provides evidence that objections extended to such inoffensive fare as "The Adventures of Robin Hood" and "The Gay Divorcee" with Fred and Ginger. The studios won enough battles to ensure that these films did become classics, but the mind reels at what they could have been if men with sexual hangups hadn't insisted that the scripts be tinkered with. As the years went by, the Production Code office recognized that society was becoming more liberal about sex, drinking and drugs- all topics that were once highly constricted on screen. Slowly, more mature dialogue and sexual situations were permitted until Jack Warner refused to tamper with the classic 1966 screen version of Edward Albee's Broadway masterpiece "Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?. The movie caused a sensation when it was released sans the Seal of Approval and went on to be an Oscar-winning boxoffice winner. Everyone sensed that the Production Code's day's were over and ultimately the ratings system was introduced in 1968 and remains in place today. This unleashed a fabulous era of filmmaking.

The impact of the Production Code seems a relic of the distant past today. We now have T.V. commercials with more sexual content than was allowed in entire feature films decades ago. However, we should remember the warning of philosopher George Santayana, who famously said "Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it." This is worth thinking about with the current resurgence of attempts in some quarters to ban certain books. If they succeed, films will certainly follow.

Nat Segaloff's "The Naughty Bits" is a highly entertaining book, written in a very witty manner. However, it's also an important book and its message about the Orwellian aspects of censorship is a sobering one.

Click here to order from Amazon