By Todd Garbarini

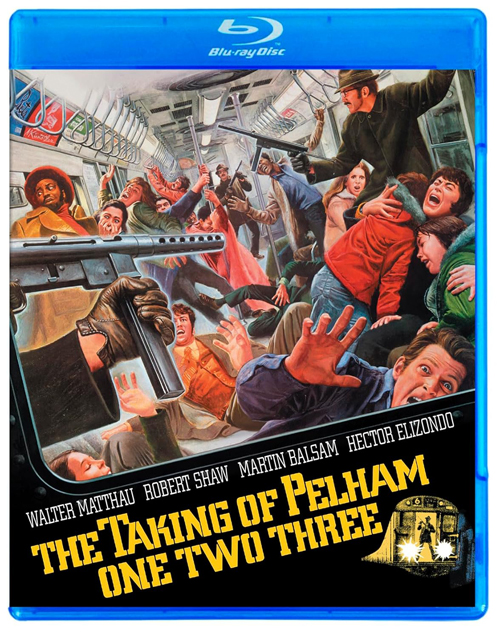

The quintessential and politically incorrect New York movie The Taking of Pelham One Two Three

(1974) is an adaptation of John Godey’s novel of the same name and is brilliantly

directed by Joseph Sargent with loads of smile-inducing and laugh-out-loud

humor. This is the not the reaction one would associate with a film that is

marketed as a taut exercise in suspense, but one needs to understand and

appreciate the era in which the film was made. New York City was in financial

distress fifty years ago, with crime, violence and drug use running rampant.

Subway cars were blanketed in graffiti, and it was a dangerous time to be

walking the streets.

Pelham is the first and best of three filmed versions of

the novel and concerns four heavily armed men, all sporting moustaches and

machine guns. They are named after colors to mask their identities (this idea

was lifted by Quentin Tarantino and used to great effect in his 1992 film Reservoir Dogs). They commandeer an Interborough

Rapid Transit (IRT) train from the subway system and hold eighteen passengers

hostage. They demand one million dollars in cash for their release within one

hour – a mere pittance in 2025’s dollars – and will shoot one passenger per

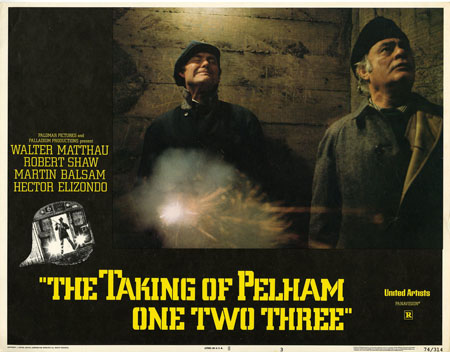

minute should the police fail to provide the money by the ascribed deadline. Robert

Shaw shines as the lead baddy and heads the superb cast which also features

Martin Balsam as a sneezing confederate; Walter Matthau is the Transit

Authority lieutenant who negotiates with Shaw and lives on his wits, making a

last-minute snap decision that buys them time; Hector Elizondo is virtually

unrecognizable as the monkey-in-the-wrench who causes problems for Shaw with his

own sense of bravado; and Kenneth MacMillian is the Borough Commander. Among

the film’s highlights are Matthau’s off-handed and embarrassing treatment of

the representatives of the Tokyo Metropolitan Subway System who are visiting; Tom

Pedi’s role as Caz Dalowicz whose no-B.S. approach to the hijackers results in

a shootout in the tunnel; Lieutenant Rico Patrone (Jerry Stiller) who reads the

newspaper and is annoyed that he is being “interrupted” by the Japanese reps touring

the facility; Lee Wallace’s turn as the Mayor (he is a near dead ringer for

Mayor Ed Koch who became the New York Mayor four years after the film’s

release) and his inefficacy in dealing with the situation at hand, including

his Deputy Mayor, played brilliantly by Tony Roberts; and Robert Weil as a transit

worker – he’s a character actor who appeared in dozens of great New York films.

It also has one of the best endings to any film of recent memory.

Pelham manages to juggle suspense and outright human hilarity

in a way that few films that I have seen are able to. Bob Clark’s Black

Christmas, released the same year, also walks a tightrope of laugh out-loud

jokes on the one hand and intense fright on the other. While the idea of a

group of men “hijacking” a subway car might seem farfetched and implausible,

how about the city’s departments co-operating collectively to achieve a

peaceful outcome to the scenario at hand? There’s one for the books!

The Taking of Pelham One Two

Three was released on Wednesday,

October 2, 1974 in New York City. What the film

captures perfectly is the sense that working people have about themselves and

their jobs, a “another day at the office” mentality as they go about their

routines. The sentiments of the film are timeless and ring true in a city where

corruption and racism run behind-the-scenes and are perfectly sized-up by Doris

Roberts’s turn as the mayor’s wife when she tells him what he will receive in

return for paying out the ransom: eighteen sure votes, exposing the

expendability of the passengers.

Pelham was also lensed in 1998 for television by Felix

Enriquez Alcala, starring Lorraine Bracco, Edward James-Olmos, and Louis Del

Grande. This version posits Vincent D’Onofrio taking the place of Robert Shaw

and updates the times with a $5 million dollar ransom. Despite the film’s star

power, the lack of profanity in the New York setting, the use of archaic train

cars betrayed by the presence of oversized ceiling fans, and a lack of tension

all combined to make the film unrealistic, filling the audience with a yen to

revisit the original.

Tony Scott made a version in 2009 with John Travolta and Denzel

Washington, this time stylizing the title with Pelham 123 as numerical

numbers and upping the ransom to $10 million dollars. Gotta love inflation. It

is a well-made version with less emphasis on humor and more on action and it is

a film that stands on its own, and one of the few times that Mr. Washington

portrays a modern day Everyman just trying to get along.

A movie-only edition of Pelham was issued on Blu-ray in 2011, and

that transfer appeared to be derived from the same master that was used on the

standard definition DVD released in 2000. A new 4K restoration was performed in

2022 by Kino Lorber and the film was released as a two-disc set on 4K UHD and standard

Blu-ray with a much-improved image. There were a host of extras added, which

can be found on this standard Blu-ray release now available following the 50th

anniversary of the film’s release:

First up is an audio commentary by film historians

Steve Mitchell and Nathaniel Thompson which runs the entire length of the film.

They are informative and highly engaging and are an example of what I love

about commentaries. They give a fair amount of information on the background of

the cast, discuss the film’s themes, and how the film’s overall look was

achieved, among many others. I am a sucker for these 1970’s gritty New York

films, and this one fits the bill.

There is a second audio commentary by actor and

filmmaker Pat Healy and film programmer/historian Jim Healy and is equally

informative and entertaining.

The Making of Pelham One Two Three is a cleverly-titled piece that runs 6:08 and

features the actual shooting of the film during November 1973 through April

1974. It is told from the perspective of a transit policeman, Carmine Foresta,

who was hired as a technical consultant on the film. He has a small role in the

film also while appearing briefly in Francis Coppola’s The Godfather Part II

(1974) and Sidney Lumet’s Dog Day Afternoon (1975). My only complaint is

the short running time. I would have loved to have seen more behind-the-scenes

(BTS) footage and hear input from cinematographer Owen Roizman, who shot The

French Connection three years earlier for William Friedkin and has managed

to capture New York City in a way that I have not seen from any other director

of photography.

12 Minutes with Mr. Grey features a 2016 interview with actor Hector

Elizondo who recalls getting the role and enjoying his time working with the

late director Joseph Sargent. He points out how the station that they shot in

was fairly clean as it was unused (there was no way to interrupt actual daily subway

traffic) and therefore free of graffiti.

Cutting on Action runs 9:09 and features a 2016 interview with film editor Gerald B.

Greenberg, who won an Oscar for cutting The French Connection. That film

is highly lauded for its memorable subway/car chase through Brooklyn, NY. In Pelham,

there is an action sequence featuring police cars racing to the subway station

to get the money to the henchmen. Mr. Greenberg gives insight into his work on

the film. Again, I would have loved a longer piece. He discusses the editing

process and being overwhelmed by the sheer amount of footage he had to work

with. He brought in another editor, Robert Q. Lovett, to help him cut the film

and help create tension and suspense.

The Sound of the City runs 9:07 and features input from composer David

Shire. He began composing music for television shows back in the 1960’s, such

as CBS Playhouse and The Sixth Sense before creating the amazing

score for Francis Coppola’s The Conversation (1974). His theme to Pelham

is no less brilliant. He recalls how the music originally sounded like a

“dissonant Lalo Schifrin.” He would later score Martin Ritt’s Norma Rae

(1979) and win an Oscar for his collaboration with Norman Gimbel for the song It

Goes Like It Goes.

Trailers from Hell with Josh Olson runs just over two minutes and he

comments on the film, rightly praising it for its accomplishments as a great

New York movie. Interestingly, the film did not make money at the box office. I

suppose that New York humor does not go over well in Montana…

There is an Image and Poster Gallery that

runs 2:20 which features artwork and black and white snapshots of scenes from

the film.

There are two radio spots, and this is something

that I truly miss from the past. I loved hearing these spots for movies on the

radio, especially the ones created for horror films. These spots are a fun

listen.

The TV spot for the film is included here.

There are also theatrical trailers for Pelham;

Don Siegel’s Charlie Varrick (1973) and Stuart Rosenberg’s The

Laughing Policeman, both from 1973 and both with Walter Matthau; Guy

Hamilton’s Force 10 From Navarone (1979); Joseph Sargent’s White

Lightning (1973) with Burt Reynolds; John Frankenheimer’s The Train

(1964) with Burt Lancaster; Tom Griers’s Breakheart Pass (1975) with

Charles Bronson; and Andrei Konchalosky’s Runaway Train (1985) with Jon

Voight and Eric Roberts.

The Taking of Pelham One Two Three is one of

the best films made during the American cinema's most riveting decade.

Click here to order from Amazon.com.