By

Hank Reineke

The ever-crowding field of horror film scholarship lost a

very important contributor when author David J. Skal was killed, New Year’s Day

2024, in an automobile collision. According

to his literary agent, Skal, riding in the passenger seat of his partner’s

automobile, was killed when a car traveling opposite crossed the median. Mr. Skal’s long-time partner, Robert Postawko,

briefly survived the terrible crash, but he too would succumb due to injuries

sustained

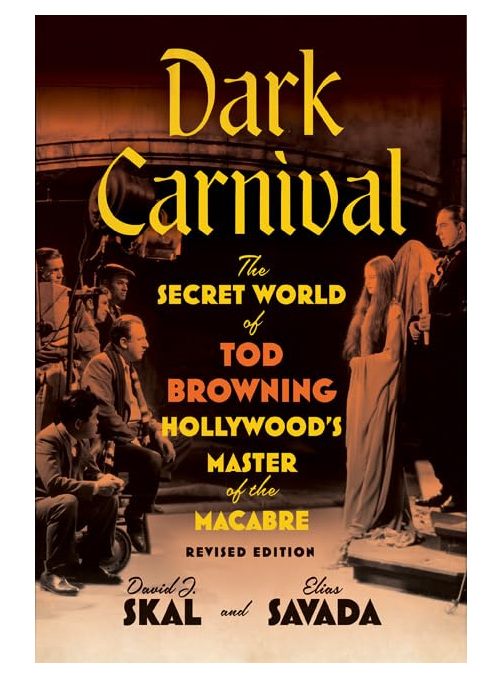

On 18 February 2025, University of Minnesota Press published

a revised edition of Skal and Elias Savada’s Dark Carnival: the Secret World of Tod Browning – Hollywood’s Master of

the Macabre. This new edition,

already well-into-the-works prior to Skal’s tragic passing, promised the “extensive

use of Browning’s personal scrapbooks and photographic archives.” Such rare material

had been unavailable to the authors at the time of the book’s original 1995 publication.

This amended version of Dark Carnival will likely serve as the final major project of David

J. Skal, the Publisher’s Foreword noting the author had, “tragically passed

away during the final weeks of this edition’s production.” As a film historian Skal certainly has left behind

a legacy. During a career of forty-odd

years, he had served as an essayist, contributor, editor, short-story writer, novelist

of both fiction and non-fiction works, and film and television documentarian. One of Skal’s most recent projects was his contributing

audio commentaries to Criterion’s Blu- ray set of “Tod Browning’s Sideshow

Shockers: Freaks (1932), The Unknown (1927) and The Mystic (1925). That glorious release of silent film classics

was released in October of 2023, only a few months prior to Skal’s passing.

If anyone was best- suited in providing Criterion with

expert commentaries re: the career of Tod (“The Edgar Allan Poe of Cinema”) Browning,

it was certainly Skal. In 1995, Anchor

Books/Doubleday first published Dark

Carnival, a seminal study of Browning’s melancholic life and his

thematically dark and unsettling oeuvre. A self-professed “monster kid,” Dark Carnival was not the first of

Skal’s book-length works to study horror-film history and the genre’s cultural

impact.

In the five years preceding Dark Carnival, Skal had published such other non-fiction studies as

Hollywood Gothic: The Tangled Web of

Dracula from Novel to Stage to Screen (W.W. Norton & Co., New York

1990) and The Monster Show: A Cultural

History of Horror (W.W. Norton & Co., 1993). The latter title remains, perhaps, his best

known work. Shortly following the original

publication of Dark Carnival, Skal

published the less academic, more pop-culture friendly encyclopedia, V is for Vampire: the A-Z Guide to

Everything Undead (Plume, 1996). The author’s primary interests, as one

might guess, tended to all things macabre.

Prior to Dark

Carnival, Tod Browning remained one of the most elusive figures of early

cinema studies. Browning was something

of a polarizing character amongst critics and peers alike: some thought him “an

unassailable auteur of cinematic darkness,” others belittled his work as that

of a hack. Some thought of Browning as a

“kindly and generous person,” others saw him as an “obsessively private” person

of “nasty disposition,” a “classic Hollywood son of a bitch with a morbid

streak a mile wide.” Celebrated by one

circle of cineaste admirers, others derided his directorial legacy as a miasma

of recycled storylines, exploitational tropes and relationship dysfunction. In the book’s prologue, the authors suggest

they found the writing of Browning’s biography as most challenging when

attempting to sort out historical fact from fiction. Their research was further hindered as the

curmudgeonly Browning chose to leave “the world no reminisces, no diaries, no

official recounts of his career, affecting an indifference to the film medium

that approached outright contempt.” He

was, from the very beginning, an outcast.

Dark

Carnival mixes straight biography and film criticism in equal

measure. Born Charles Alpert (“Tod”)

Browning in Louisville, Kentucky, 12 July 1880 – or, perhaps, as early as 1874. Even his correct birthdate was obfuscated,

Browning’s personal account differing from the official record. As a young man Browning wasn’t particularly

religious in belief, though he did cultivate a lifelong obsession with

baseball, alcohol and – especially - show business. Browning was particularly interested in

performing as ringmaster. As a child he

would put on penny admission shows in a shed behind his family home.

Uninterested in a life tending horses or working for the

railroad, Browning was fascinated by the exotic pageantry to which he was

introduced in and around Louisville. He

was especially taken by the annual Mardi Gras-style atmosphere of the Satellites of Mercury Parade, of the colorful,

roving gypsy encampments he encountered outside of the newly christened

Kentucky Derby at Churchill Downs, of the raucous entertainments offered in the

vaudeville playhouses and burlesque theatres aligning the city’s “raffish”

riverfront.

When, at age nine in 1890, a devastating tornado swept

through Louisville, Browning was witness to the terrible structural and human

wreckage left in the storm’s wake. It

may have been a result of this experience that Browning became haunted, perhaps

obsessed, by the sight of the maimed, crippled human bodies that littered the

streets of his hometown. Browning would

marry Amy Louis Stevens in March of 1906, but as he had a roguish “roving eye,”

he abandoned his first wife in the summer of 1909, having “not contributed

anything towards her support or maintenance.”

The truth was his true real love was show business. Oddly, Browning became obsessed with those whom

many saw as the lowest-rung practitioners of show business: carnival folk and their

peripatetic gypsy troupes. His people

were the barkers of ballyhoo, the sideshow freaks, geeks, midgets, sword

swallowers, snake handlers, fire eaters, contortionists and “wild men” from

parts unknown. Those of higher station status

saw such performers as migratory panhandlers: alcoholics, swindlers and

grifters, all scuffling for the pennies and nickels of gullible gentile

audiences. The symbiotic relationship between

the two disparate groups was transactional: the book alleges that, “The carny

ethos divided the world into two rigid camps: show people and everyone else –

“suckers,” marks,” and “rubes.”

Browning would throw his lot in with the former. He did a spell as a carny, allowing himself

to be buried alive nightly as a so-called “Hypnotic Living Corpse.” He later graduated from carny life to the stages

of vaudeville and burlesque houses. There he worked alongside magicians and illusionists, carefully studying

the deceptive tricks-of-the-trade of the psychic-mesmerists. A chance meeting in 1913 with D.W. Griffith gave

Browning the opportunity to travel to Los Angeles and act in no fewer than

fifty one-reel comedies circa 1913-1915. In 1915 he ambitiously moved to the director’s chair. Browning would helm a number of one or two

reel silent melodramas as director, many of these early storylines reworked and

revisited later in his career.

His alcoholism was becoming more obvious. One raucous “roadhouse revel” led to a

terrible collision of his car with a railroad flatbed. The collision fractured Browning’s leg and caused

him serious internal injury and the loss of most of his teeth. Tragically, the unfortunate passenger in

Browning’s vehicle was killed instantly, the impact so violent that imprints of

the flatbed’s iron rails were found pressed into the victim’s skull. The authors note that none of Browning’s colleagues

interviewed could recollect him ever talking about the incident, much less offering

any “”feelings of responsibility” or complicity in the death of his friend.

Following a period of convalescence, Browning returned to

directing silent pics for Metro. In

1918, Browning came to the attention of Irving G. Thalberg, then with Universal. Signing with Universal, Browning helmed a

number of five and six reelers for the company, two of which featured one of

their big silent stars, the actress Priscilla Dean. Those two films, The Wicked Darling (1919) and Outside

the Law (1920), would introduce Browning to their otherwise unheralded

co-star, Lon Chaney.

Though Browning would freelance on productions of several

other film companies, both he and Chaney would follow Thalberg in the latter’s defection

to MGM. It was during this period with

MGM that Browning’s melodramatic, envelope-pushing cycle of silent films – all made

in collaboration with Chaney - that solidified his reputation as a bankable director

of merit: The Unholy Three (1925), The

Blackbird (1926), The Road to

Mandalay (1926), The Unknown

(1927), London after Midnight (1927),

The Big City (1928), West of Zanzibar (1928) and Where East is East (1929). When sound film production became the norm,

things changed.

The authors of Dark

Carnival remind, “Neither Browning nor Chaney was comfortable with the

prospect of a talking screen: their art, after all, was firmly rooted in the

tradition of pantomime.” Indeed, Chaney would

appear in only one sound film prior to his passing in August 1930, Jack

Conway’s talking version of The Unholy

Three. Robbed of his primary

collaborator, Browning would direct his first sound production for MGM, The Thirteenth Chair (1929), before signing

a contract with Universal to remake his own Outside

the Law (1930), Edward G. Robinson now cast in the role Chaney played a

decade earlier.

While working on The

Thirteenth Chair, Browning made the odd decision to cast a “perversely

inappropriate” actor, Bela Lugosi, as a police inspector of mysterious

personage. The authors suggest Lugosi’s

against-type casting – abetted by the actor’s uber-melodramatic performance and

lugubrious speaking voice – was intentional. Browning had been “colluding with the actor” to get Universal to

consider the offer “of a screen test for the film version of Dracula.” If this was the case, their gambit was successful.

Lugosi would claim the title role and Browning would secure the director’s

chair. Universal’s production of Dracula (1931) would, for all of its

staginess, missed opportunities and long silences – prove Browning’s greatest

success.

In contrast, Browning’s follow-up to Dracula, Iron Man, was a

too-talkie and too stagey melodramatic photoplay that, similarly to the sound

version of Outside the Law, opened to

mixed reviews. Still confident in his

talent, MGM would lure Browning back into the fold with a generous fifty-thousand

dollar salary and three picture commitment. As further inducement, the studio offered Browning an additional 50K

“adjustment check” for a trio of previous MGM pics Browning had done

considerable advance work on – projects that had sadly fallen to the wayside

due to Chaney’s illness. It was a

speculative investment in Browning’s career the studio would come to regret.

The film Browning would choose to lens on his return to

MGM was the notorious Freaks

(1932). This pre-code film, in which a troupe

of carnival “freaks” and human oddities avenge the cruel manipulation and

murder plot against one of their own, retains the ability to shock even in 2025. The book’s chapter (“Offend One and You

Offend Them All”) concerning the production – as well as the subsequent public

and critical outrage following the release - of Freaks, is revelatory and fascinating, a compelling historical

read-through.

Though Browning would go on to direct four more pictures

in the wake of the controversies kicked up by Freaks, the stinging criticism to his grim melodrama signaled the

beginning of the end of his career as director. Two of his remaining four pics, Mark

of the Vampire (1935, a sound remake of his own London after Midnight) and The

Devil Doll (1936) are passably interesting mystery-horror mellers, though

both would underperform at the box office. The other two, Fast Workers

(1933) and Miracles for Sale (1939)

were efficient if unremarkable comedies. Unfortunately, and more damnably, these latter two pics had, similarly

to Freaks, not only performed below

expectation, but were outright money losers for MGM.

Though Browning continued to pitch ideas to MGM for

future projects, his proposals were shunted aside or rejected outright. In time, Browning saw the writing on the wall:

he had, in his own estimation, been “blackballed” from the film industry. He would “officially” retire in January of

1941, quietly retreating to his cottage in Malibu with his second wife, Alice (nee

Wilson). Married in 1917, Alice would remain

at her husband’s side (with periodic separations) despite Browning’s

indiscretions – including a scandalous “drunken dalliance” with the under-age

actress Anna May Wong. Following Alice’s

passing in 1944, Browning became a virtual recluse – a brooding, gloomy

melancholic with few close friendships.

Browning would spend his final years in near-isolation,

drinking prodigious amounts of bottled beer and spending his days and insomniac

nights watching baseball games and black-and-white movies on television. Prior to his death in October 1962, he demanded

that no memorial or viewing be staged to commemorate his passing. Only a drinking-buddy – a house painter known

only as “Lucky” – was allowed to visit his corpse and proffer one last post-mortem

toast.

Browning’s biography is, to

say the least, a unique one. Having

lived a life nearly as haunted and troubled as his cinematic melodramas, I’m

guessing it is unlikely that Browning’s story will ever be told better than here

in the pages of Dark Carnival. The greatest platitude I can ascribe to Skal

and Savada’s masterful study is that it rekindles genuine interest in the

director’s filmography. The book ignites

a desire to seek out as many of Browning’s extant films as one can source. The best books regarding cinema studies are

those that leave readers curious to visit or revisit old film titles, either famous

or forgotten. A superbly researched and

elegantly written study, Dark Carnival

is, without question, one such book.

Click here to order from Amazon