By Lee Pfeiffer

I'm always somewhat amused when I read articles that look back on the 1960s as the decade in which cinematic Westerns went out of style. The theory is that the new screen freedoms appealed to younger viewers and indeed they did. "Easy Rider" and "Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice", both released in 1969, would have never made it to theater screens in the prior decade. However, Westerns were far from dead. They may not have dominated movie screens in the manner they traditionally did, but the genre was still thriving and co-existing with the breakthrough films being made a generation of inventive young turks. Case in point: the year 1969, which saw the release of three classic Westerns: Henry Hathaway's "True Grit", Sam Peckinpah's "The Wild Bunch" and George Roy Hill's "Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid". The latter inspired an Emmy-winning documentary that has appeared on special edition videos of the film and is now streaming on Amazon Prime. The show was made during production of the film and narrated by George Roy Hill but it was not telecast until after the movie had been released to sensational reviews and boxoffice. Thus, when watching the show, it's from an interesting perspective, as the director admits he doesn't know how well his ambitious film will be received. In fact, "Butch Cassidy" would help to not only reinvent the Western in a hip, funny manner but would also inspire the countless "buddy" movies that would follow in its wake. They would all feature characters patterned after Butch and Sundance's habit of making quips even in the face of deadly threats.

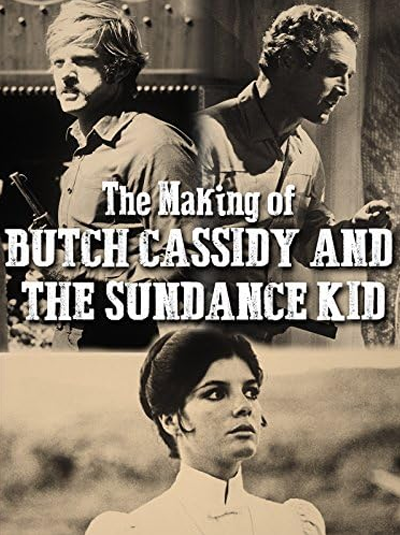

The program provides a master class in filmmaking, demonstrating how many talented people are crucial to bringing a movie to the screen. In this case, Hill constantly refers to the contributions of cinematographer Conrad Hall, already an esteemed industry veteran and composer Burt Bacharach, who decided to go with a contemporary-sounding score that worked surprisingly well. Hill's commentary isn't sanitized (though his expletives most certainly would have been censored for T.V. broadcast.) The challenges he faced are made clear starting with stars Paul Newman and Robert Redford, who were to play inseparable best friends. In real life, the two actors had not known each other prior to filming. Luckily, they bonded immediately. Hill seems to have been not so enamored with his leading lady, Katharine Ross, who he alludes to having some frustrations with and dismisses with some faint praise, not to be mentioned again despite being shown throughout the program. Hill demonstrates how he was open to hearing creative suggestions from his stars and sometimes going with their judgment.

The most enjoyable aspects of the program, which was impressively directed by Robert Crawford, Jr., is the way it demonstrates the monotonous aspects of movie-making, which quickly strips the glamour away. If you have ever watched a major movie being filmed then you know most of the time is spent just waiting around as the director, actors and technicians discuss strategies and even the seemingly easy scenes require a great deal of preparation and the involvement of countless professionals. Hill also points out the magic of filmmaking through the use of deceitful methods. When Butch and Sundance make their famous jump into the rapids, the stars were filmed atop a cliff in Colorado but the actual jump was shot with two stuntmen at the famed Fox Ranch studio set in California, using the same lake where scenes from "Our Man Flint" and "Planet of the Apes", among countless others, were filmed.

George Roy Hill and his stars and crew thought they had a winner with "Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid". They were probably wrong only in the sense that it transcended being a hit and became an all-time classic, reaffirming Paul Newman as an endurable leading man and launching Robert Redford to superstardom. None of them would realize that their second act would be even bigger, with their combined talents reunited for the Oscar winning Best Picture "The Sting" four years later.