By

Hank Reineke

One

of the more fascinating aspects of the Spanish horror film is that the

country’s most famous exports were produced during the near forty year

dictatorial regime of Falangist leader Generalissimo

Francisco Franco. In interviews

conducted following the passing of the repressive dictator in 1975, actor Paul Naschy

(the so-called “Lon Chaney of Spanish horrorâ€) often expressed bemusement regarding

the restrictions imposed by Spanish censors on his films. Naschy’s horror films were (arguably, I

suppose) of either very modest or completely non-political in their design - if

not their subtext.

Paul

Naschy (aka Jacinto Molina Alvarez) was greatly influenced by the celebrated

cycle of gothic horror and mystery films produced by Universal Studios in the

1930s and 1940s. The primary difference

between these monochrome films and those Naschy would lens beginning 1968 is

unmistakable: most of his films,

including the colorful Count Dracula’s

Great Love (1971), owed more to the more contemporary themes and style of

Britain’s Hammer Studios. Spanish

implementation of less discreet on-screen sexuality and a seemingly limitless

supply of blood plasma packets pushed even Hammer’s edgiest offerings to the tame,

more modest borders of exploitation cinema.

Nevertheless,

the horror films released in this otherwise repressive environment were neither

produced under the tightest of restriction nor designed in an effort to avoid

offending the sensibilities of right-wing prudes. As anyone who has ever enjoyed a Paul Naschy

or Jess Franco film can attest, Spanish horror offerings of the 1960s and 1970s

are suffused with gory imagery, eroticism, savagery, envelope-pushing scenarios…

and generous dollops of female nudity.

Unlike

most censorship boards, the Spaniards didn’t seem terribly concerned with flashpoints

involving on-screen immoralities or scenes of sickening violence. Their primary concern was simply that film characters

demonstrating unwholesome peccadilloes or otherwise satanic non-Christian traits

not be identified as being of wholesome Spanish heritage. So a werewolf bearing the Eastern-European the

Slavic surname of Daninsky was permitted, as were godless Hungarian vampires

and Prussian hunchbacks. Those in the Spanish

film industry were more than happy to ring international box-office cash

registers with their appropriations; the atheistic commies of Eastern Europe were

welcome to the authorship of the malevolent creatures spawned from their

decadent folklore.

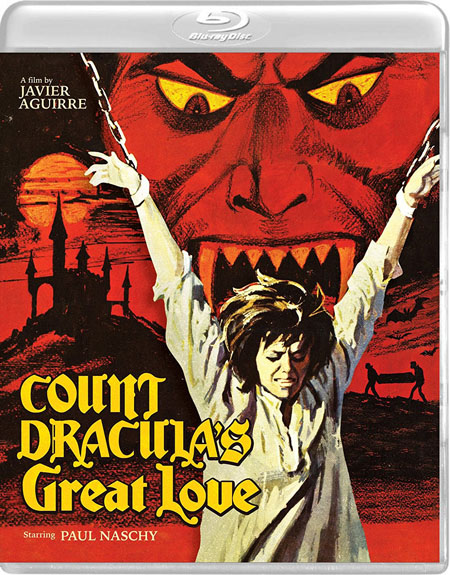

Javier

Aguirre’s Count Dracula’s Great Love

(original title El Gran Amor Del Conde

Dracula) was Paul Naschy’s only on screen appearance as Brom Stoker’s

legendary vampire Count Dracula. The

actor would in his long career assume the roles of practically every vanguard monster

of the “classic horror†pantheon. In a

lengthy series of Spanish-European co-productions, Naschy would don the makeup

and costumes of vampires, mummies, hunchbacks, werewolves… he even tackled the dual

role of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Well

regarded by filmmakers and contemporaries as a hard-working, earnest

actor-writer-director, he was also remembered as a humble, modest man. His greatest pride was when horror fans

whispered his name with the same reverence reserved for the greatest icons of

the genre: Karloff, Lugosi, Chaney, and

Price.

Count Dracula’s

Great Love

opens, more or less, as nearly every other Dracula film. Following a violent breakdown of the

horse-carriage somewhere near Hungary’s mountainous Borgo Pass, a group of five

travelers - one gentleman and four buxom beauties - seek temporary help at the

supposedly derelict sanitarium of Dr. Kargos. The good doctor is nowhere to be found – at least, not yet – but the

castle’s new tenant, the soft-spoken, candelabra carrying Dr. Wendell Marlow

(Paul Naschy) soon answers the door of what’s rumored to be the ancestral home

of the Vlad (“The Impalerâ€) Tepes, the bloody historical Prince of Wallachia.

At

first sight Marlowe is no cruel Vlad Tepes. Naschy’s Marlowe is a supposed Austrian

aristocrat and an apparent softie: he’s a thoughtful and gracious sort,

self-effacing, and unrelentingly polite. In fact, when the stranded travelers are brought into the anteroom,

they’re not only immediately welcomed with courtesy but offered accommodation and

meals for the week. This is necessary,

he explains, as there are no hotels in the area; he owns no transportation modes

and his forthcoming order of supplies are seven days away.

The

four blond girls at first don’t seem terribly grateful for the Dr.’s generous

hospitality. One whispers a complaint almost

immediately, moaning her displeasure that the castle is a dreary, gloomy sort

of a place. If director Aguirre wanted

to convey a palatial sense of doom and menace to match that description, he was

clearly let down by his art department. The castle interiors are generally bright and immaculately clean save

for the odd cobweb or two drooping forlornly from lighting fixtures. The castle’s cellar, where the delivery of a

wooden crate of human-length proportion arrives at the film’s beginning, is a

bit more atmospheric: here we find the

stony labyrinth passageways, the moss covered walls, the rat-infested rooms we

might expect.

One

of the stranded travelers finds the genial Dr. Marlowe a physically attractive

specimen. That said, she’s reminded by a

friend that her tastes in men are her own. The friend prefers a man “slimmer and taller.†(Naschy was hardly a cadaverous Count, a muscular

man of stocky build and approximately only 5’ 8†in height). With little alternative the girls choose to

make themselves at home, now resigned to their unplanned stay at the castle. By day two they’re making the most of it and immodestly

sunning their naked bodies in the estate’s opaque pool. Though the castle grounds are in disrepair

and in serious need of some landscaping, they discover the wooded acreage is nonetheless

conducive to long negligee-garbed walks in the moonlight.

It isn’t long before a veil of mystery descends upon the stranded. There’s a creepy silent guy with pupil-less eyes walking the hallways at night, and everyone is beginning to wonder why Dr. Marlowe never seems to be around during daylight hours. The group’s lone virgin Karen (Haydee Politoff) is intrigued by the castle library and its stacks of dusty, cob-webbed books. Among the library’s holdings is the journal of Dr. Van Helsing, the world renowned expert on vampirism. Karen decides this is worthy night-time reading material and its pages reveal to her that a vampire’s power can be restored to full capacity if it draws blood from the neck of a virgin. Having already suffered the consequences of this a scenario, Van Helsing balefully inks his desire that such a virgin is never born.

I don’t think I’m giving anything away here by revealing that Dr. Marlowe is, in reality, Count Dracula. It’s pretty much telegraphed from the movie’s opening scene. If Bela Lugosi’s and Christopher Lee’s Dracula’s were pretty reprehensible, immoral sorts, Naschy’s Count is more of a tortured soul ala Lon Chaney Jr.’s Lawrence Talbot. In this sense, Naschy brings to Dracula the same sympathetic sensibilities he brings to his most famous on-going character, the tormented werewolf Waldemar Daninsky. Naschy’s Dracula is similarly a very lonely, gentle soul, or at least when he’s not torturing and murdering locals. He’s desperate for romance but trapped in the dark, loveless shadows of an eternal life-long curse.

Which is too bad as Naschy finds his true love in the personage of the mutually smitten Karen. She is attracted to the gentle man she knows only as Marlowe and the two get even closer when several of the other houseguests go missing… and begin feeding on one another in the creepy dungeon beneath the castle. In a commentary track included on this set Naschy’s relates – in his native Spanish, of course – that some critics thought Count Dracula’s Great Love a romantic rather than horror film. While romantic imagery certainly plays a role in every staging of a Dracula adaptation, this film is, by no means, a precursor to Twilight. (On the same commentary Naschy ruminates that Aguirre’s film was the template for Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992). There are similarities to be sure, but if Count Dracula’s Great Love is a romantic film, there are also enough gratuitous scenes of blood-letting and blood-licking to sate the most morbid appetites of 1970s horror-movie aficionados.

Though Dracula/Marlowe and Karen eventually share a romantic idyll of the physical sort, he has not yet put the fateful bite of the undead on her. Having already inoculated the other houseguests to vampirism, Dracula’s team of bloodsuckers wreaks havoc on a small village. There they kidnap a local innocent girl whom they whip mercilessly, suspend from the ankles and bleed dry over the rotting skeleton of Dracula’s daughter… whom they hope to revive by doing so.

In a surprising twist, Dracula seems to choose his great love for Karen over his ambition to revive his own daughter from the dead. Of course to accomplish this, the girl must willingly succumb to a tryst with his incisors. Not willing, Dracula’s titular great love – who by now is also his imprisoned soul-mate (this happens to a lot of us married folk, let’s face it) – remembers a sure fire deterrent gleaned from Van Helsing’s crackled old book. She fashions a cross from two sticks of wood as Dracula sweeps toward her. Will love triumph over evil? Or will Dracula, the fabled Prince of Darkness, finally lose patience with his recalcitrant lover and put the bite on her? I’ll never tell.

Vinegar Syndrome’s Blu Ray/DVD combination of Count Dracula’s Great Love features a scanned and restored 2K transfer from a 35mm internegative source. It’s presented in a Widescreen 1:85:1 ratio in DTS-HD mono audio. The set features five “Reels†(Chapter Selections) as well as a wonderful new-to-this-set “Video Interview with Actress Mirta Miller.†The set also features a well-edited Spanish-language commentary track with both actor Paul Naschy and director Javier Aguirre. Both the film proper and the special features include optional English and Spanish sub-titles and English/Spanish language selections. There’s also an informative and well-researched eight-page booklet written by Mirek Lipinski, a recognized authority on all things Euro-horror. The set also includes the obligatory still gallery and U.S. theatrical trailer.

CLICK HERE TO ORDER FROM AMAZON