BY NICHOLAS ANEZ

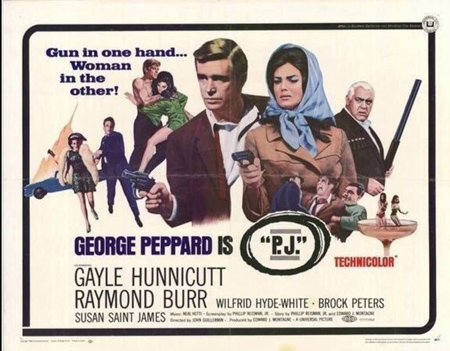

Business isn’t exactly booming for private

detective Peter Joseph Detweiler, better known as P.J. His makeshift office is

in a bar belonging to his only friend Charlie, his sporadic jobs include

entrapping cheating wives and he is not above drowning his sorrows in liquor. So

when wealthy magnate William Orbison offers him a substantial fee to be a

bodyguard for his mistress, Maureen Prebble, he jumps at the chance. What P.J.

doesn’t know is that Orbison has already hired someone else to commit a murder.

How this murder and the shamus’s new job intersect is the crux of the terrific

1968 neo-noir from Universal, P.J. (U.K.

title: New Face in Hell.)

Private detectives were prominent in the late

1960s and included Harper (1966), Tony Rome (1967), Gunn (1967), and Marlowe (1969).

P.J. appeared in the midst of this

surplus, which may account in part for its box office failure. The movie quickly

disappeared, at least in its original form. Due to one extended and bloody

sequence in a gay bar as well as to other scenes of violence and sexuality,

Universal drastically cut and re-edited the movie for its television network

presentation. Since then, it has never been officially released on home video

and the original version may be lost forever.

Philip Reisman, Jr.’s screenplay is based on

his original story co-written with producer Edward Montagne. The script initially

unfolds as a conventional mystery but gets increasingly complicated with each

twist and turn. Maureen appears to definitely need a bodyguard, in view of threatening

letters as well as a shot fired into her bedroom. And there is no shortage of

suspects who would like to see her dead. Orbison’s emotionally fragile wife,

Betty, resents the very thought of her husband’s paramour. Betty’s relatives despise

Maureen because of her emergence as principle beneficiary in Orbison’s will. Orbison’s

Executive Assistant, Jason Grenoble, due to his apparent affluent upbringing, is

displeased about being used as a flunky. Making P.J.’s job more difficult is Orbison’s

decision to take everyone, including relatives and mistress, to his hideaway in

the Caribbean island of St. Crispin’s. And it is in this tropical setting that

P.J. is forced to kill a suspect. This seems to be the end of the case. But it

is really only the end of the second act. The third act is filled with

intrigue, deception, blackmail and three brutal deaths.

John Guillermin is an underappreciated

director who created admirable films in many genres, including mystery, adventure,

war and western as well as the disaster and monster genres. His success could perhaps be due not only to his

skill but to a style that is unobtrusive. He directs P.J. in a straightforward fashion, not allowing any directorial flourishes

to interrupt the flow of the story. With cinematographer Loyal Griggs, he cleverly

contrasts the seedy sections of New York City with the natural beauty of St.

Crispin’s. However, this beauty is soon tainted by the presence of Orbison, whose

wealth the island’s economy requires to flourish. Guillermin allows each of the

characters within Orbison’s contingent enough screen time to make an impact.

Basically, they all appear to be self-centered, greedy and nasty. Orbison is

especially sadistic, in addition to being notoriously miserly. Maureen doesn’t

apologize for providing sexual favors in exchange for future wealth. Betty is

willing to be repeatedly humiliated to obtain her customary allowance. Grenoble

continually demeans himself to keep his well-paid position. And then there is butler

Shelton Quell, who is not as harmless as his effeminate mannerisms suggest. This

is a sordid group of characters that P.J. is involved with but his dire

financial state has apparently extinguished his conscience, particularly since

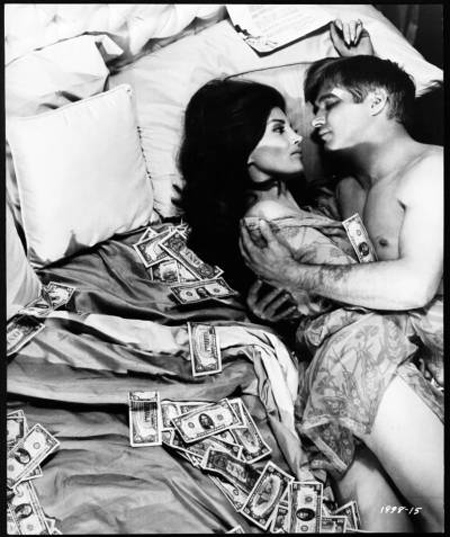

he soon becomes intimately involved with the body that he is guarding. P.J.’s

essential irony arises from the fact that he is equally greedy, at least

initially. He also seems to be morally bankrupt. When he encounters Orbison

leaving Maureen’s cottage, it doesn’t faze him that they have just engaged in a

quickie. P.J. knows that he has sold his gun to Orbison just as Maureen has

sold her body.

In the early 1960s, George Peppard became a

major star in expensive films such as The

Carpetbaggers and How the West Was

Won. In mid-decade, he starred in another big-budget film, The Blue Max, the first of three movies

he would make with John Guillermin. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, he starred

in several smaller-budgeted movies. While some of them, especially Pendulum and The Groundstar Conspiracy are exceptional, others are unremarkable.

The commercial failure of these movies diminished his star status and he was

relegated to series television. This was regrettable because he had genuine

star quality as well as considerable talent.

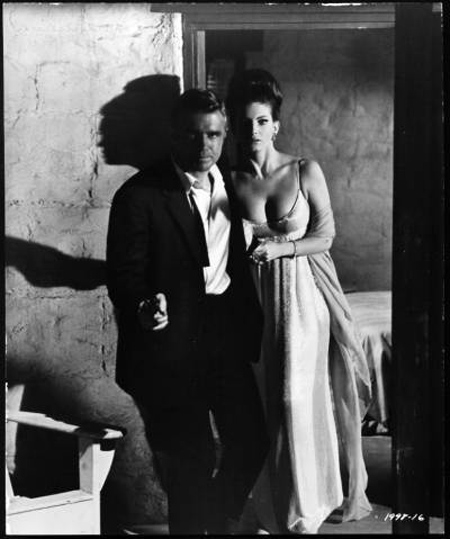

As P.J. Detweiler, Peppard creates a unique

private eye that puts him apart from his cinematic brethren. P.J. initially appears

disillusioned with his life and work. Like many film noir protagonists, he is one

of society’s alienated outcasts. He is not just down and out but seems resigned

to his dismal situation. When he is offered the lucrative position of

bodyguard, he is so destitute that he agrees to a humiliating audition of

fisticuffs. As he begins his job, he appears impassive to the decadence of

Orbison’s environment. However, after he has been duped and discarded, he

asserts himself and becomes a traditional detective who is determined to pursue

clues and solve the mystery. But unlike traditional detectives, he doesn’t

derive any pleasure from the solution to the crime. The fact that he has been maneuvered

into facilitating a murder has emotionally drained him. At the end of the film,

he forces a cheerless smile at Charlie but he is unable to sustain it,

replacing it quickly with a look of despair. All of these emotions are

reflected in Peppard’s superb portrayal.

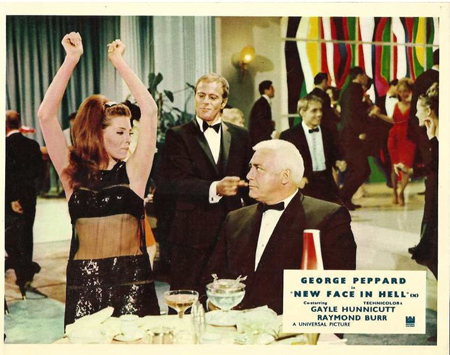

As William Orbison, Raymond Burr splendidly returned to the villainous roles that he had portrayed in previous decades before becoming a household name on television as lawyer Perry Mason, a role he played for nine years. P.J. was released six months after Burr started his second successful series as police chief Ironside, a role he would portray for eight years. Audiences who were accustomed to seeing him embody honorable characters must have been shocked to view his malevolent Orbison. Though he projects a sophisticated veneer for Orbison, Burr fully evokes his perverted obsession with wealth and power through his modulated tone and menacing visage. With his atypically silver hair and imposing size, he conveys malignant authority. In the scene in which Orbison brings his wife and mistress together, the actor’s expression of merciless pleasure invites unmitigated contempt. Burr’s Orbison deserves an honored position among noir’s loathsome villains.

As Maureen Prebble, Gayle Hunnicutt provides a convincing performance that cleverly borders between helpless victim and femme fatale. Colleen Gray, who appeared in noirs of the 1940s and 1950s, stands out among the capable supporting cast as the pathetic Betty Orbison. Jason Evers as Grenoble and Severn Darden as Quell also deserve mention. On the side of law and order, Brock Peters as St. Crispin’s chief inspector and Bert Freed as a New York City police lieutenant are effective in suggesting their helplessness amidst the surrounding corruption. And though he is only in a few scenes, Herb Edelman makes an impression as the supportive Charlie.

The film’s conclusion is a bitter one. P.J. can no longer be a detective in good conscience because, though he didn’t intentionally set out to kill Grenoble, his acceptance of employment from Orbison created the circumstances that led to the killing. Even though he was manipulated into pulling the trigger, he is as morally responsible as he is physically. This why he looks so totally dejected in the last sequence. When P.J. walks forlornly away into the mean streets, his future is a bleak one.

P.J. is an excellent movie that deserves rescue from oblivion, but only in its original form.