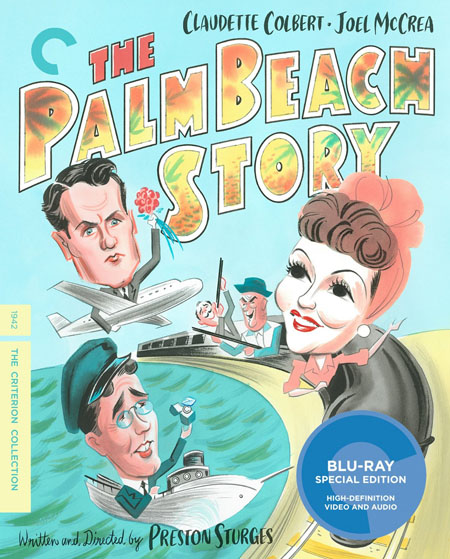

WACKY WEDDED BLISS

By Raymond Benson

Preston

Sturges was a rare breed in Hollywood in the early 1940s—he was a

writer/director auteur who penned

original comedies and directed them himself. Perhaps Chaplin—and Keaton, to a

degree—were the only other filmmakers up to that point who did the same,

picture after picture. Sturges began as a screenwriter authoring some of

Hollywood’s better comedies of the late ‘30s; finally, he told Paramount he

would sell them his script for The Great

McGinty only if they allowed him to direct it. The studio bosses relented

when Sturges took a cut in salary to do both jobs. McGinty was a hit and went on to win a screenplay Oscar for

Sturges. Then, during the war years, Sturges enjoyed his remarkable run before

succumbing, in the later years of the decade, to the inevitable “falling out of

fashion†that so often occurs in Tinsel Town.

Sturges’

comedy is sophisticated, intelligent, and witty; but it’s also wacky, off the

wall, and spitfire fast. He specialized in screwball comedy—i.e., absurdly zany

love stories between two likable but eccentric characters—and The Palm Beach Story, released in 1942,

is a prime example. Following his masterpiece (but, at the time, misunderstood

and not well received financially) Sullivan’s

Travels, Palm Beach stars Joel

McCrea (“Tomâ€) and Claudette Colbert (“Gerriâ€â€”Tom and Gerri, get it?) as an

unhappily married couple who split up and ultimately get back together. Classic

screwball comedy structure. What makes the film different from other screwball

comedies is what happens in-between. And at the beginning.

Ah,

the beginning. Over the main title credits, we see a series of strange clips

that appear to be taken from later in the picture—but they’re not. In fact,

they’re never really explained at all, which does cause some confusion with the

audience. This opening has been debated by film scholars ever since the movie’s

release. It’s actually exposition, but cut down to brief snippets of visuals,

edited to the tune of a rollicking William

Tell Overture. We see a maid frightened by an imposing figure—she faints. A

concerned priest is at the altar, looking at his watch. We see Colbert, tied up

and gagged in a closet. And then we see Colbert in a wedding dress, rushing to

get ready? Is she the same Colbert as before? After that we

discover McCrea in wedding garb rushing to get in a car—obviously late for the

ceremony. But in the car he changed into another

set of wedding clothes. The bridal Colbert runs by the maid, who screams

and faints again. The tied and gagged Colbert breaks out of her binds and kicks

her way out of the closet. The recovering maid sees her, screams, and faints. Then the parties rush to the chapel—where

McCrea and Colbert (which one?) get married. The caption reads: “And they lived

happily ever after... or did they?â€

We

don’t really find out what was going on in the credits until the end of the

movie in a somewhat contrived but typically Sturges-style explanation of what’s

been going on in the picture. It’s not a spoiler to reveal that Colbert plays

twin sisters, but McCrea also plays

twin brothers. The two sisters are in love with one of the McCrea twins (not “Tomâ€),

and he is about to marry the one who is not named Gerri. However, Gerri has

tied up her sister and taken her place at the altar—but somehow “Tom†has taken

his brother’s place at the chapel—and Tom and Gerri—the wrong couple—get

married. At least that’s how I interpret

it.

After

five years of marriage, Tom and Gerri are at each other’s throats (but they

really do love each other, they just don’t realize it yet). Gerri leaves for

Palm Beach and Tom follows her. Gerri begins a relationship with billionaire

Rudy Vallee, and Tom is snared by Vallee’s maneating sister, Mary Astor, and

then things really get complicated.

Throw

in Sturges’ standard stock company of character extras—William Demarest, Sig

Arno, Robert Dudley, Franklin Pangborn, Arthur Hoyt, Chester Conklin, Jimmy

Conlin, Robert Warwick, and several others (all faces you will recognize but

won’t know their names) and you’ve got one crazy oddball of a movie. And it’s

marvelous.

Criterion’s

4K digital restoration looks gorgeous, as always (how does Criterion manage to get the best-looking presentations of

black and white classic films on Blu-ray?). There are two new video interviews

with (a) writer and film historian James Harvey about Sturges and his works,

and (b) comedian and actor Bill Hader, also about Sturges and the picture. A

WW2 propaganda film, written by Sturges for the State Department, Safeguarding Military Information, is

included (and features Sturges regular Eddie Bracken). A 1943 radio adaptation

by Screen Guild Theater is also included, plus the informative essay by critic

Stephanie Zacharek in the booklet.

It’s

too bad that Preston Sturges’ flame burnt out by the end of the forties—he was

a talent that was often miles ahead—and above—his peers. The Palm Beach Story, while perhaps not his best work, is certainly

indicative of the man’s genius.

CLICK HERE TO ORDER FROM AMAZON