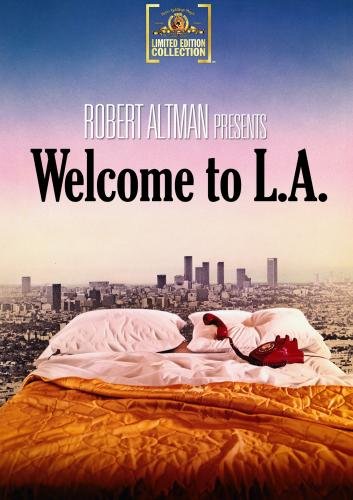

“THE CITY OF

ONE-NIGHT-STANDSâ€

By Raymond Benson

Alan

Rudolph directed two forgotten horror flicks in the early seventies before joining

Robert Altman’s team; he served as Altman’s assistant director and in other

positions for several years. In the interim, Altman produced Rudolph’s third

feature film, Welcome to L.A., which

premiered in 1976 and was released to the general public in the spring of 1977.

Rudolph’s

best work is obviously inspired by Altman’s method of telling the personal

stories of an ensemble of quirky and neurotic characters over a sprawling

canvas (M*A*S*H, Nashville, A Wedding, Short Cuts, for example). Rudolph’s Welcome to L.A. does just that, only this

writer/director’s style is even more loosey-goosey than Altman’s. Rudolph’s

approach is much more poetic, slower, and dreamier. More serious, too, I might

add.

Keith

Carradine plays Carroll, a character much like the guy he played in Nashville—a songwriter who is coolly

arrogant and a cad, but all the women love him anyway. He’s been living in

England when his agent and former lover, Susan (Viveca Lindfors), hooks him up

with singer/musician Eric (Richard Baskin, who wrote all the film’s songs); so

Carroll comes back home to L.A. He doesn’t get along with his millionaire

father (Denver Pyle), but manages to seduce his father’s girlfriend,

photographer (Lauren Hutton). Throw in the realtor of his rented house (Sally

Kellerman), a seriously-disturbed and unhappy housewife (Geraldine Chaplin), and

a wacky housekeeper who vacuums topless (Sissy Spacek), and we’ve got a real

merry-go-round of one-night-stands (in fact, one of the songs beats us over the

head that they’re “living in the city of the one-night-standsâ€).

There

are other men, too—Harvey Keitel is quite good as Chaplin’s husband, who

happens to work for Pyle and has his sights set on some co-stars, and John Considine,

who is married to Kellerman—he, too, manages to have dalliances with other

female cast members. The entire movie’s “plot,†as it were, is how all of these

characters will hook up with the others in the space of a few days.

But

what the movie is really about is

loneliness. These people are middle-to-upper-class Hollywood types and they’re

caught in the malaise that Los Angeles of the mid-seventies had become (and

Rudolph’s filmmaking smacks of the 1970s in look and feel—not that this is a

bad thing). The picture seems to be saying that even if you’re rich and

beautiful/handsome and talented, you still need love and connection—but

unfortunately, the one-night-stand mentality is a dead end, as many of the

characters learn. And Carradine’s character, something of an omniscient

angel/devil, floats through this world caring about nothing but himself, but

therein lies a central truth—this guy is the unhappiest of them all.

The

film is beautifully shot, and if you can get past the somewhat now-pretentious

and arty device of people looking into mirrors and delivering soliloquies, you

may be impressed with the mise-en-scene.

Some folks, I remember, criticized Baskin’s songs and singing as being

annoying; on the contrary, I’ve always found the movie’s soundtrack to be very

well done. After all, the point of the picture is that it’s a musical journey

through vignettes that dramatize the lonely search for interconnection.

The

film is available as an MGM burn-to-order title. A card before the movie claims that the transfer was made from the “best

sources possible,†which means they probably used an existing print rather than

negatives to strike the DVD. Colors have faded significantly and the image

looks rather drab, which is unfortunate.

Nevertheless, if you’re a fan of Rudolph, or Altman, and you want to experience

something different that was hitting the art house circuit in the

mid-seventies, take a look. I would place Welcome

to L.A. near the top of Alan Rudolph’s idiosyncratic, but usually quite

interesting, work.