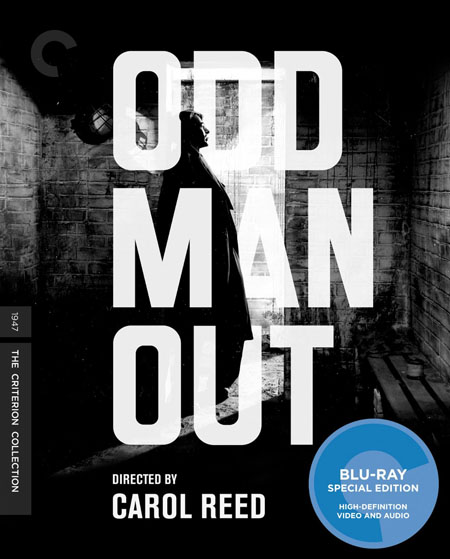

“A PINT OF BRITISH

NOIRâ€

By Raymond Benson

Film noir wasn’t just

relegated to American Hollywood films of the forties and fifties. It was

something of an international movement, albeit an unconscious one, for it

wasn’t until the late fifties that some critics in France looked back at the

past two decades of crime pictures and proclaimed, “Oui! Film noir!â€

Britain

was doing it, too. Carol Reed’s 1947 IRA-thriller-that-isn’t-an-IRA-thriller Odd Man Out is one of the best examples

of the style. Robert Krasker’s black and white cinematography pulls in all the

essential film noir elements—German

expressionism, high contrasts between dark and light, and tons of shadows. Other

noir trappings are present, such as stormy

weather, night scenes, exterior locations, bars, shabby tenements, a lot of smoking,

and a crime. And, for a movie to be “pure noir,â€

there must not be a happy ending. Odd Man

Out fulfills that last requirement with shocking bravura.

James

Mason stars as Johnny, the leader of “the organization†in an unnamed Northern

Ireland city; it isn’t difficult to connect the dots and assume the

organization is the IRA and the city is probably someplace like Belfast (where

much of the second unit photography was done on the sly; the rest of the film

was shot in studios and locations in England). Johnny escaped from prison a few

months back and has been in hiding, secluded in a house with his girlfriend

Kathleen (the beautiful Kathleen Ryan) for months. He has gathered a small gang

to rob a mill for money to support their cause. The problem is that Johnny has

gone a bit “soft,†and isn’t properly prepared for the job. Nevertheless, the

four men pull off the caper, but of course it goes wrong. Johnny is shot in the

shoulder, he unwittingly kills a man in self defense, and he is separated from

the other gang members. The rest of the film is a D.O.A.-style story of the next twenty-four hours or so as Johnny

eludes capture from the police on the streets, all the while losing blood and

his life. So we know he’s probably not going to make it and we wait for the

inevitable—but what happens until that fateful ending (which manages to

surprise us anyway with an unexpected twist in how it’s done) is incredibly

suspenseful.

Odd Man Out is one of the most

engaging and thrilling British films of the 20th Century. Period. It certainly

rivals Reed’s The Third Man, which is

also an excellent model of British noir.

Mason is terrific as he stumbles around the streets, delusional and suffering,

practically bouncing from one obstacle to another with no safe haven in sight.

Other familiar British and Irish faces crop up—Robert Newton, Cyril Cusack, Dan

O’Herlihy, F. J. McCormick—and Kubrick fans might recognize a younger Paul

Farrell (the tramp from A Clockwork

Orange) as a bartender named Sam.

Criterion’s high-definition digital restoration looks marvelous, naturally. Once again,

the company’s mastering for Blu-ray outdoes the competition. The image is sharp

and without blemishes for the most part, and appears as if the film was made

yesterday. Extras include a new interview with British cinema scholar John Hill

on the picture; “Postwar Poetry,†a new short documentary; a new interview with

music scholar Jeff Smith about composer William Alwyn and his gorgeous score; a

nearly-hour-long 1972 documentary featuring James Mason revisiting his hometown

in Ireland; and a radio adaptation of the film from 1952, starring Mason and

O’Herlihy. The essay in the booklet is by critic Sara Smith.

All

of these supplements are very good, but the reason to run out and buy this

Blu-ray release is the film itself. Odd

Man Out is a landmark crime picture with wonderfully eccentric Irish

characters, lush atmosphere, and film

noir traits galore. Highly recommended.

CLICK HERE TO ORDER FROM AMAZON