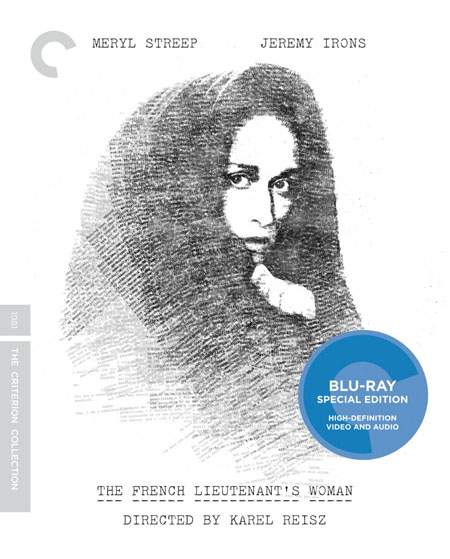

“THE FRENCH

LIEUTENANT’S WOMAN†(1981; Directed by

Karel Reisz)

(The

Criterion Collection)

“PARALLEL

OBSESSIONSâ€

By Raymond Benson

John

Fowles’ 1969 novel, The French

Lieutenant’s Woman, was a literary sensation, a best-seller, and a work

deemed “impossible†to film because it broke conventions and played with

narrative structure and point of view. And yet, there were several attempts in

the 70s to adapt the difficult Victorian story to something cinematic.

Apparently Dennis Potter took a shot at writing a screenplay at one point, but

it was playwright Harold Pinter who cracked the problem and presented the tale of

obsession, infidelity, and shame as two parallel stories—one in the Victorian

past, as in the book, and one in the present, dealing with the actors making the film we’re watching.

It was a unique and original approach to the material. With Karel Reisz at the

helm, the film adaptation became a critically-acclaimed art house delight.

Reisz,

a Czech director working in England, was at the forefront of the British New

Wave of the 60s with such pictures as Saturday

Night and Sunday Morning, Morgan!,

and Isadora. He brilliantly realizes

Pinter’s script with the help of the gorgeous cinematography by the great Freddie

Francis and the superb performances by Meryl Streep and Jeremy Irons. It was

Streep’s first starring role (she had previously held supporting parts and won

her first Oscar for Supporting Actress for Kramer

vs. Kramer) and it earned the actress her first Oscar nomination in the

Leading Actress category. For many, especially in the U.S., this was the first

time Irons was seen on the big screen (he had previously done much work for

British television and had a small part in one feature film). Narratively, it’s

Irons’ movie—he plays the protagonist—but it is definitely Streep, with her

hauntingly quiet portrayal of Sarah, the fallen woman, who leaves an indelible

mark.

The

parallel stories follow illicit love affairs. In the present, actors Mike

(Irons) and Anna (Streep) are making a movie called The French Lieutenant’s Woman. Both are married to other people,

but they have an on-location affair while filming in West Dorset, England. Coincidentally,

the characters they play in the movie—Charles and Sarah—have a scandalous

affair in the same setting, but in the Victorian era. The point of the picture

seems to be that nothing has changed since the late 19th Century in terms of

morality, social mores, and how misplaced passion can wreck a life. Sarah is a

mysterious outcast in the seaside town of Lyme Regis, the subject of much gossip

as being the “French Lieutenant’s Whore,†i.e., she had an adulterous

relationship with a married, visiting French soldier. Charles is a

paleontologist working in the village; he is engaged to marry a well-to-do

local girl, but he unwittingly becomes obsessed with Sarah. This, of course,

leads to the man’s ruin. In both cases, the aftermath of the affairs leave

devastations... or do they?

In

Fowles’ novel, the consequences of Charles’ and Sarah’s affair is played out in

three different endings. It is up to the reader to decide which is the most

plausible—or morally acceptable. For the film, Pinter has twisted this conceit

into the two analogous storylines with dissimilar outcomes. Very clever indeed.

Perhaps Pinter’s script—which was nominated for an Adapted Screenplay Oscar—is

the real star of the picture.

Besides

the Oscar nods for Streep and Pinter, the film was nominated for Art Direction,

Costume Design, and Film Editing.

Thought-provoking,

moody, beautifully shot, brilliantly written, and exquisitely acted, The French Lieutenant’s Woman is ripe

for rediscovery as an important piece of British cinema from the early 80s.

The

Criterion Collection does its usual bang-up job with a new 2K digital

restoration and an uncompressed monaural soundtrack. The images look marvelous.

Reisz’s attention to detail in the period setting is a feast for the eyes.

Supplements

include new interviews with Streep and Irons, editor John Bloom, and composer

Carl Davis (whose score is evocative and sublime); a new interview with film

scholar Ian Christie about the making and meaning of the film; an episode from The South Bank Show from 1981 featuring

Reisz, Fowles, and Pinter; and the theatrical trailer. The essay in the booklet

is by film scholar Lucy Bolton.

While

Chariots of Fire may have taken the

Oscar gold for 1981, for me the finest British picture that year was The French Lieutenant’s Woman.

CLICK HERE TO ORDER FROM AMAZON