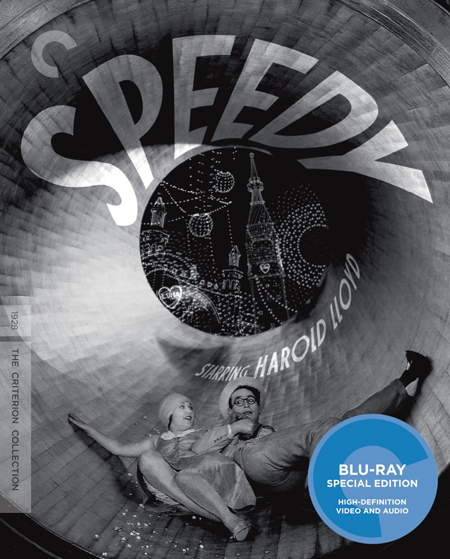

“THE GLASSES IN

MANHATTANâ€

By Raymond Benson

This

is the third excellent release of a Harold Lloyd film by The Criterion

Collection and it’s a welcome addition to sit on the shelf along with the

previous two (Safety Last! and The Freshman). I mentioned in a review

of one of the previous releases how wonderful it was that Criterion was

re-issuing Lloyd’s catalog. Most of his work had been unavailable for many

years; I grew up with Chaplin and Keaton, of course, but with Lloyd, not so

much. It’s a pleasure to discover him in this way.

Speedy was Lloyd’s final

silent film, released in 1928. Although he usually made his pictures in

Hollywood, this time he wanted to shoot in New York City. Bruce Goldstein,

director of repertory programming at New York’s Film Forum, explains in an

interesting supplement, “In the Footsteps of Speedy,†that Lloyd took his leading lady Ann Christy and canine

co-star King Tut on the railroad across country to make the movie. Quite a bit

was shot there, but in the end, though, nearly half the picture was also made

on the streets of Los Angeles, doubling for New York—and the matching up is

sometimes not very convincing. Still, it’s revelatory to see New York as it was

in 1928—Times Square, Washington Square, Sheridan Square, Brooklyn and Coney

Island—it’s all here, exactly the way it was. The establishing shot for Manhattan

was that of the Woolworth Building, because at the time that was the tallest and

most famous structure! Fascinating stuff.

The

story concerns Pop Dillon’s horse-drawn streetcar, the last one of its kind in

the big city, the tracks of which the railroad baron wants to demolish to make

way for progress. Pop’s daughter Jane (Christy) is engaged to Harold “Speedyâ€

Swift (Lloyd), who takes it upon himself to make sure Pop’s livelihood isn’t

taken away or at least insure that he’s fairly compensated. Why Harold is

nicknamed “Speedy†is not really clear... he’s the usual “Glassesâ€

character—naive, enthusiastic, positive—who works at one job and then another,

happily trying to make ends meet so he can marry Jane.

Much

of the movie is a sightseeing tour of New York—the Coney Island scenes are

especially enjoyable, since Speedy and Jane ride many of the classic attractions

that don’t exist anymore. King Tut, the stray dog who picks Speedy to be his

master, is adept at many tricks and serves as a terrific little sidekick.

The

biggest draw, though, at the time of the film’s release, was the appearance of

Babe Ruth in a minor role as himself. Speedy is a baseball enthusiast—a plot

point that never really amounts to much—and he has a chance to give the Babe a

ride in his taxi (Speedy’s current job). The Babe invites Speedy to see the

game at Yankee Stadium, where our hero is able to avoid the cops who are after

him for traffic tickets. Babe Ruth had already appeared in a couple of films,

in one as himself and in another, a work of fiction called Babe Comes Home, as a baseball player very much like himself. Speedy came at the right time—1928 was the second year in a row the

Yankees won the World Series.

Speedy is certainly good

fun, although for my money I think both Safety

Last! and The Freshman are better

pictures. There are plenty of chases and slapstick bits, but the “thrillâ€

stunts Lloyd is known for are not in this one. Here’s hoping Criterion

continues its releases of Harold Lloyd classics, especially Grandma’s Boy, Girl Shy, and The Kid Brother.

The

movie looks terrific in a new 4K digital restoration from elements preserved by

the UCLA Film & Television Archive; there’s a musical score by Carl Davis

from 1992, synchronized and restored and presented in uncompressed stereo (and

it sounds great!). A new audio commentary is by Goldstein (see above) and

Turner Classic Movies director of program production Scott McGee. In addition

to the Goldstein documentary mentioned earlier, there is a selection of rare

archival footage of Babe Ruth, presented by David Filipi, director of film and

video at the Wexner Center for the Arts. A new video essay featuring stills

from deleted scenes is narrated by Goldstein. There’s also a cute collection of

Harold Lloyd’s home movies, narrated by his granddaughter, Suzanne Lloyd, as

well as a newly restored Lloyd short from 1919—Bumping Into Broadway, with a 2004 score by Robert Israel. The

booklet contains an essay by critic Phillip Lopate.

A

must-buy for fans of silent comedy and for those who want to enrich their lives

with the genius of Harold Lloyd.

CLICK HERE TO ORDER FROM AMAZON