“PUT THE BLAME ON

MAME, BABEâ€

By Raymond Benson

Life Magazine called Rita

Hayworth “The Love Goddess.†Make no mistake—she was primarily known as one of the sex symbols of the 1940s. Nevertheless,

she was also a talented actress and a terrific dancer (she held her own with

Fred Astaire in a couple of movies). Strikingly beautiful, Hayworth was the

type of star who lit up the screen and oozed charisma. And her big breakthrough

to that position in Hollywood was Gilda,

the 1946 part-noir, part melodrama

that contained many of the iconic images for which Hayworth is famous.

Film noir historian Eddie

Muller, in a new interview included as one of the supplements, says Gilda is not film noir, although it’s got all the trappings. This is true. It’s

certainly made in the style of a film noir—the contrasting black and

white cinematography by Rudolph Maté (who later became a

director in his own right) is clearly derived from German expressionism, the

characters are untrustworthy and suspicious, and there’s a femme fatale.

But

wait—is Gilda really a femme fatale?

Not really. Sure, she’s manipulative and uses her sexuality to get the men in

her life to do what she wants; but Gilda is not a bad person—she’s just caught

in an uncomfortable situation and is acting out because she’s unhappy. A minor

subplot dealing with Mundson’s business dealings—with former Nazis—doesn’t

totally qualify Gilda as being a film noir, either. No, this is a movie

soap opera, but that doesn’t mean it’s not an entertaining piece of Hollywood

glamour that captures a cynical post-war mood prevalent in a lot of Hollywood

fare of the late 40s.

The

story takes place in Buenos Aires just as World War II is ending. Johnny

Farrell (Glenn Ford, in one of his significant roles as well) is a gambler,

drifter, and “tough guy†bumming around Argentina. There he meets a rich man,

Ballin Mundson (George Macready), who offers Johnny a job being his right hand

man at the casino. The two men work together well and become very chummy—until Mundson

returns from a weekend away with a gorgeous wife. She is, of course, Gilda

(Hayworth)—and it is immediately obvious she has a history with Johnny.

The

rest of the film is a melodramatic clash of wills within this triangle, and it’s

not a smooth ride. Much is made of the word “hate,†but in most cases in this

picture, that word really means “love.â€

Hayworth

is quite good in the movie. She performs two song-and-dance numbers (for the

casino audience), but her singing voice is dubbed by Anita Ellis. These are signature

tunes—“Put the Blame on Mame†(done as a sultry striptease—almost), and “Amado

Mio.†(One wonders how Gilda managed to rehearse with the band and lighting

crew to do tight, theatrical show-stopping acts, seemingly on the fly.) At any

rate, Hayworth smolders as Gilda, and

she takes over every frame she’s in. Ford is fine, although he sure has a funny

way of hitting people. Macready provides the requisite sinister authority over

the other two characters, just as he would a decade later in Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of Glory.

Production

aspects are top notch—the photography, music, editing, sets, and especially the

costume design. Hayworth’s gowns are right out of the catalog of Hollywood dreams. Perhaps the only weak

element is the writing. The story feels jumbled a bit, but the dialogue is rich

with memorable one-liners. “If I was a ranch, I’d been named the Bar Nothing,†Gilda famously says. The

screenwriters had challenges on their hands. The Production Code prevented the

filmmakers from fully exploring the relationship that is really going on between Johnny and Mundson. It’s pretty muted, but

it’s there, folks. Ford’s character is much more enamored of his boss than a

regular employee would be. How that wrinkle plays into the stew once Hayworth

arrives is the heart and soul of the picture. Read between the lines and you’ll

fathom what the writers intended, but

couldn’t quite get past the censors.

The

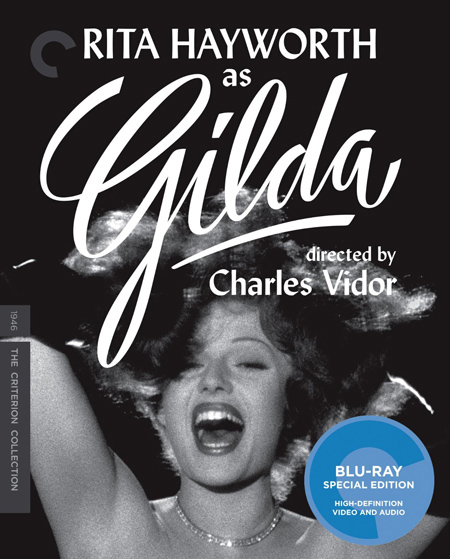

Criterion Collection’s new high-definition digital restoration, with an

uncompressed monaural soundtrack, looks and sounds exemplary. A wonderful audio

commentary by film critic Richard Schickel, made in 2010, accompanies the film.

Supplements

include the previously mentioned interview with Muller; an interesting 2010

discussion with filmmakers Martin Scorsese and Baz Luhrmann about the film;

“Hollywood and the Stars,†a 1964 television show about Hayworth’s career up to

that point; and the trailer. The fold-out insert contains a poster of Gilda on

one side and an essay by critic Sheila O’Malley.

The

tag line on the movie poster read: “There never was a woman like... Gilda!†That’s probably true. Put the Blame

on Mame, indeed!

CLICK HERE TO ORDER FROM AMAZON