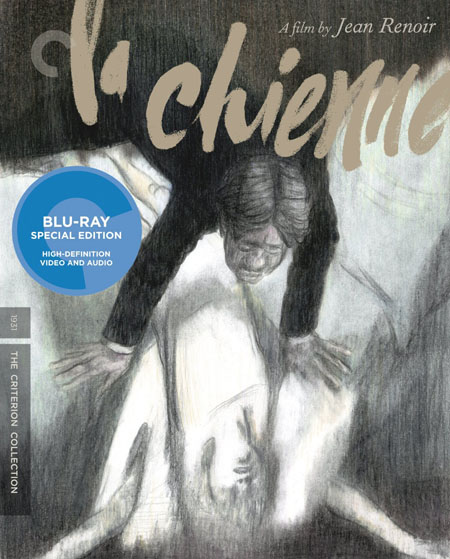

“THE STREETWALKER AND

THE SUCKERâ€

By Raymond Benson

Fans

of Fritz Lang’s film noir of 1945, Scarlet Street, may do well to take a

look at this little French gem from 1931. Lang’s film was a Hollywood remake of

La Chienne, which was based on a

novel by Georges de La Fouchardière (it was also

adapted into a stage play by André Mouëzy-Éon).

More significantly, La Chienne was

the second—and first feature length—sound film by the great Jean Renoir.

Renoir

had done well in the silent era, but the invention of talkies presented the

filmmaker with a larger palette of tools with which to craft some of his

greatest works. Beginning with La

Chienne, Renoir became France’s premiere director, a position he held for a

decade.

La Chienne translates as “The

Bitch,†and viewers may question which woman in the picture the title is referring

to—the lead, Lulu, a beautiful blonde “street woman†(a con artist and often a

prostitute), who serves as the femme

fatale of the story (and wonderfully played by Janie Marèze)... or the wife of our protagonist, such a shrew of a

woman that there’s no wonder why we sympathize with the poor schmuck, Maurice

(portrayed by the brilliant Michel Simon), a banker and part-time painter who

does everything he can to get away from his marriage and set up Lulu as his

mistress. Of course, Lulu is really being played by her lover and pimp, the nasty Andre (played by real-life Parisian

gangster Georges Flamant, who was also an amateur actor). Maurice is merely the

mark, the sucker who is seduced by lust and led to his ruin.

Unlike Scarlet Street, La Chienne is

more melodrama than film noir. Renoir

handles the material well without making it overwrought, and he succeeds in

developing fine character studies of the three leads. Those familiar with the

director’s later masterpieces such as Grand

Illusion (1937) and The Rules of the

Game (1939) will find this early work fascinating. Renoir’s signature mise-en-scène is easily identifiable,

even in its baby steps. Also impressive are the street scenes shot on

location—this was the real Paris of 1931, displayed in glorious black and

white.

Michel Simon, like Renoir, was one of

France’s biggest film artists. Originally Swiss, Simon made French silent films

and later had a long run as an actor in talkies. He has a distinctive Bassett

Hound face, perfect for betraying first the joy and then the pain Lulu puts him

through. According to Renoir scholar Christopher Faulkner, who talks about the

movie in one of the disk’s supplements, apparently Simon fell in love with the

actress playing Lulu off-screen. But, like in the film, Janie Marèze was seeing Flamant, and this relationship was encouraged

by Renoir. Not long after production was completed, Marèze was killed in an automobile accident with Flamant at the

wheel. At the funeral, Simon allegedly threatened Renoir with a gun, but he

must have calmed down, for Simon starred in a subsequent Renoir feature, the

excellent Boudu Saved from Drowning

(1932; incidentally, this was remade in Hollywood in 1986 as Down and Out in Beverly Hills).

The Criterion Collection’s release

features a new, restored 4K digital transfer that looks so pristine and sharp

you might think the film was made last week. There’s an uncompressed monaural

soundtrack and a new English subtitles translation. Supplements include an

introduction to the film by Renoir himself, shot in 1961; the aforementioned

interview with Faulkner on the movie; a sparkling new restoration of Renoir’s

first sound film, the short On purge bébé

(also 1931), a comic bauble based on a one-act play by Georges Feydeau and also

starring Michel Simon; and a ninety-five minute 1967 French TV program

featuring a conversation between Renoir and Simon. An essay by film scholar

Ginette Vincendeau adorns the booklet.

A fine, notable release, and a must for

lovers of European cinema.

CLICK HERE TO ORDER FROM AMAZON