“EVERYTHING BUT THE

KITCHEN SINKâ€

By Raymond Benson

In

the late 1950s, a film movement emerged in Britain known as “Free Cinema.†Some

of the U.K.’s most celebrated filmmakers of the 1960s and 70s were among its

practitioners—Lindsay Anderson, Karel Reisz, Lorenza Mazzetti, and Tony

Richardson. The directors made low budget, short documentaries about the

working class with an almost deliberate “non commercial†sensibility. It was

radical and exciting, and it was a precursor to the British New Wave that

dovetailed with the French New Wave that was so influential on filmmakers

everywhere.

Many

of the pictures of the British New Wave, released between 1959 and 1964,

focused on characters described as “angry young men,†and the films themselves

were referred to by critics and theorists as “kitchen sink dramas.†This was

because the movies were presented in a harsh, realistic fashion and were indeed

about the gritty, working class lives of “ordinary†(but actually,

extraordinary) people. Some of the titles you’ll recognize—Look Back in Anger, Room at

the Top, Saturday Night and Sunday

Morning, The Loneliness of the Long

Distance Runner, This Sporting Life,

and others.

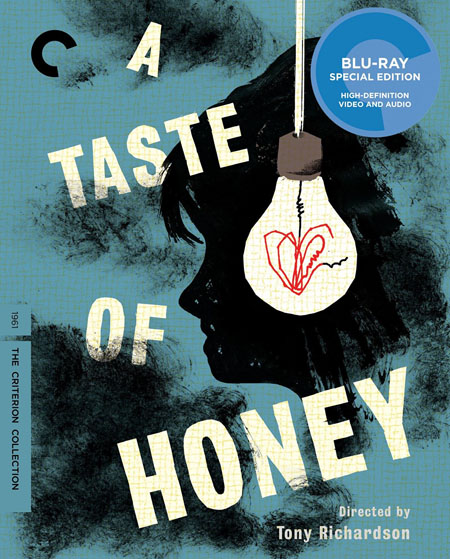

A Taste of Honey, released in 1961

and directed by Tony Richardson, was a product of the early Free Cinema

Movement and the British New Wave. Based on a controversial but highly

successful stage play by first-time dramatist (at age 19) Shelagh Delaney, Taste is remarkable for several reasons.

For one, it is about an “angry young woman.â€

It is also shockingly frank for its

time. The British Board of Censors approved the picture only for persons over

the age of 16, for it deals with these then taboo subjects—female promiscuity,

alcoholism, interracial sex, pregnancy out of wedlock, and homosexuality. There’s

even a bit of nudity. (As a “kitchen sink drama,†it indeed has everything

but!)

The

story focuses on Jo (expertly played by newcomer Rita Tushingham), who lives

with her tramp of a mother, Helen (Dora Bryan), in a Manchester ne’er-do-well

working class environment. Helen seems to flit from man to man and doesn’t care

all that much for her daughter, now 16. Jo, frustrated and dissatisfied with

the status quo, has a relationship with a black sailor (Paul Danquah) who’s in

town for a few days. Helen runs off with a new beau, Peter (Robert Stephens), and

gets married, leaving Jo alone and pregnant. Jo then finds solace by

befriending a gay man, Geoffrey (courageously portrayed by Murray Melvin), who

moves in with her until Helen decides to leave her husband and return.

This

was bold stuff in 1961. In fact, it was still against the law in England to be

homosexual at the time. It is to Delaney’s credit to bring the Geoff character

to life on the stage without saying he’s

gay, but letting the audience know without a doubt that he is. The film version

accomplishes the same thing (Melvin is the only cast member who was also in the

original stage production), handling the subject matter with honesty, grace,

and empathy.

Filmed

entirely on location, the picture captures the grime and hardships of these

people but also manages to be brilliantly entertaining. The acting is

top-notch, and Richardson’s direction is flawless. The camerawork by Walter

Lassally, often hand-held, provides a documentary feel to the proceedings that

expound on the earlier stylistic traits of the Free Cinema Movement.

The

Criterion Collection Blu-ray release features a new, restored 4K digital

transfer with an uncompressed monaural soundtrack, and it looks marvelous.

Supplements include: new interviews with Rita Tushingham and Murray Melvin (the

latter’s is especially enlightening); an audio interview with Tony Richardson

from 1962, accompanied by stills and clips; an excerpt from a 1960 television

interview with Shelagh Delaney; a 1998 interview with DP Walter Lassally; a new

piece with film scholar Kate Dorney about the film’s origins and the stage

production’s director, Joan Littlewood; and Momma

Don’t Allow, a 1956 Free Cinema documentary short co-directed by Richardson

and Karel Reisz and shot by Lassally. The booklet contains an essay by film

scholar Colin MacCabe.

While

the storyline and subject matter might sound drab and dire, A Taste of Honey does have an

under-flavor of sweetness that makes viewing the film a truly rewarding

experience. Recommended.

CLICK HERE TO ORDER FROM AMAZON