“INGMAR WOODYâ€

By Raymond Benson

Woody

Allen has written and directed several dramas over the years (none of which he

appears in)—and there are indeed a few that are worthwhile endeavors. The 1988

release, Another Woman, might be one

of Allen’s least-seen films, and yet it belongs in a list of the artist’s

solid, good pictures—not one of his

masterpieces, but certainly not a clinker (with over forty-six titles, his oeuvre runs the gamut!)

A

few months ago, I reviewed Allen’s first drama, Interiors, here at Cinema

Retro and acknowledged

the obvious influence of Ingmar Bergman in the work. But it was stated that Interiors was really more Eugene O’Neill

than Bergman. Here, Another Woman is

definitely channeling Bergman; in fact, many critics spotted the similarity—or homage—to the Swedish master’s classic Wild Strawberries (1957), in that the

film is about a person reflecting on a past life, discovering painful truths,

and resolving to change paths moving forward. In Strawberries, the protagonist is an old man; in Woman it’s a female turning fifty. The

Bergman comparison is made even stronger by the fact that Bergman’s longtime

and Oscar-winning cinematographer, Sven Nykvist, is the DP on Allen’s picture.

He shoots it in striking, picture-perfect color.

Marion

(sensitively played by the great Gena Rowlands) is an intelligent philosophy

professor on sabbatical, and she’s hoping to write a book. She’s in her second

marriage to Ken (Ian Holm), who is also in his

second marriage. His teenage daughter from the first union, Laura (Martha

Plimpton), is closer to Marion than her own mother (Betty Buckley). Marion has

rented an apartment to get away from construction noise at her home so that

she’ll have peace and quiet to write. However, the walls are thin and she is

next to a psychiatrist’s office. Marion can hear the patients talk about their

problems. One particular subject, Hope (Mia Farrow), is pregnant and suicidal.

Listening to Hope triggers a crisis in Marion, who begins to face turning fifty

and what her life has meant. She soon discovers that she’s been in denial over

a lot of things, mainly that she isn’t perceived by people close to her in ways

that she had thought.

The

film then takes the Wild Strawberries route

as Marion reflects on events from her past (shown in flashbacks and dream

sequences). Instances of infidelity, jealousy, elitism, and abortion come back

to haunt her—and Marion resolves to do something about it.

Compared

to Interiors, Another Woman is much more confident in its direction, and the

control over the piece is more relaxed. Experience counts, for Allen had one

other dead-on drama under his belt (the dreadful September) and several pieces one could call “dramedies†before

tackling Woman. His work here with

Nykvist is masterful. The cast is excellent—besides everyone previously

mentioned, the film also features Blythe Danner, Sandy Dennis, Gene Hackman,

Harris Yulin, John Houseman (in his last screen performance), Frances Conroy,

Philip Bosco, and David Ogden Stiers.

The

music—made up of classical and Allen-esque jazz selections—is also very

effective. Satie’s Gymnopedie No. 1 serves

as a theme of sorts, and its melancholy pervades the picture.

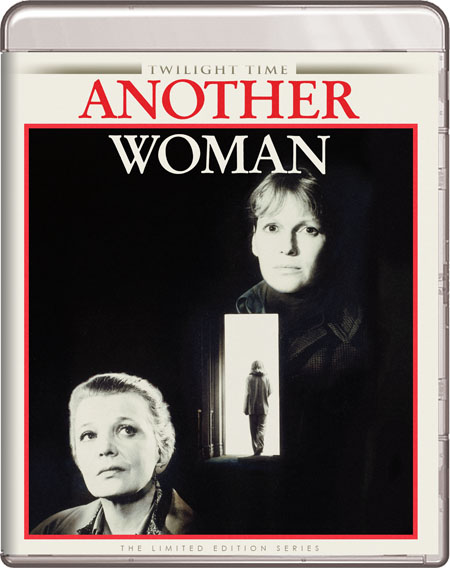

Twilight

Time’s new Blu-ray release looks marvelous, showing off Nykvist’s photography

with vivid hues. As with most Allen releases, though, the supplements are

sparse—only a theatrical trailer and an isolated music score are present on the

disk. A perceptive essay by Julie Kirgo adorns the inner booklet.

The

eighties may be Woody Allen’s strongest decade of work, and Another Woman is a fine example of the

period.