“HITCH BEGINSâ€

By Raymond Benson

The

British silent film period of director Alfred Hitchcock is simultaneously

interesting and frustrating. It’s the former because it allows one to view a

genius at the very beginning of his career—the kernels of motifs and themes, as

well as stylistic choices, can be spotted and analyzed. It’s the latter because

only one or two of the nine silent pictures he made are truly memorable and

most are available today solely as poor quality public domain transfers.

The

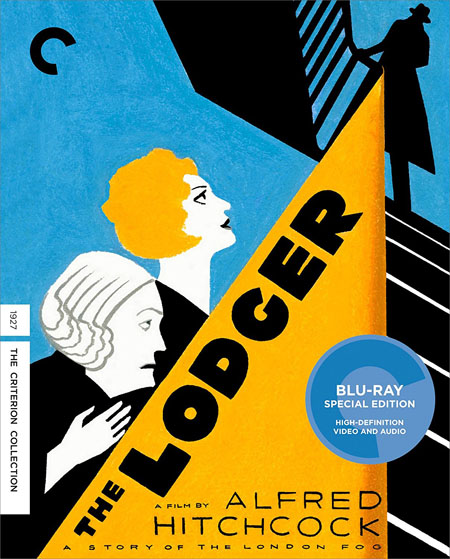

Criterion Collection has just released a bang-up, marvelous new edition of

Hitchcock’s most celebrated silent work, The

Lodger—A Story of the London Fog. The disk also contains one of the rarer

silent titles, Downhill (also 1927),

which might be reason enough for Hitchcock enthusiasts to purchase the package.

A

bit of history: Hitchcock was working for Gainsborough Pictures under the

auspices of Michael Balcon (one of the major studio heads of early British

cinema). The young filmmaker was sent to Germany in 1925 to make his first two

pictures so that he could “learn†the craft from the then-masters of

expressionistic storytelling. He made The

Pleasure Garden and The Mountain

Eagle, both of which were deemed not good enough to release in the UK

(interestingly, they were both released in the US in 1926, making America the

first English-speaking country to see a Hitchcock film!). Hitch’s third

completed title, The Lodger, almost

suffered the same fate. Balcon and others at the studio didn’t like it, and it

was only after a film critic named Ivor Montagu came in and made suggestions

for changing some title cards and reshooting some scenes, that The Lodger was finally released.

It

was an immediate success, both critically and financially (prompting

Gainsborough to release The Pleasure

Garden and The Mountain Eagle in

the UK, almost two years after they were made). The Lodger is also considered to be the first true “Hitchcock filmâ€

in that it’s a crime picture that presents many visual and thematic elements to

which he would return (including but not limited to—the notion of the “wrong

man,†blondes, handcuffs, sexual fetishism, and expressionistic lighting and

camerawork). For a silent film, The

Lodger is totally engrossing and fascinating, guaranteed to entertain even the

most jaded viewers who can’t abide movies without talking.

The

story is loosely based on the Jack the Ripper case (adapted from a novel by

Marie Belloq Lowndes). A serial killer of blonde women known as “the Avengerâ€

is loose in London. A mysterious stranger (Ivor Novello) rents the upstairs

flat in the home of Daisy, a blonde fashion

model and her parents. Daisy’s boyfriend is a cop, but she’s not really that

interested in him—she’s more attracted to the stranger—the lodger who asks that

all portraits of blonde women be removed from his room. Of course, it isn’t

long before the lodger is suspected of being the Avenger.

Novello,

who was a matinee idol at the time, is striking in the picture. Granted, in

1927, movies of this ilk were melodramatic, the acting exaggerated, and the

pacing meticulous. Nevertheless, Novello’s good looks and pained expressions

contribute to the building of suspense. The boarding house itself also becomes

a character in the story, as outlined by art historian Steven Jacobs in an

interesting supplement on the disk that discusses Hitchcock’s use of

architecture in his pictures.

Unfortunately, The Lodger is the highlight of the filmmaker’s silent period. Everything else is pretty dreary, for he didn’t make another crime movie—what we would consider a “Hitchcock filmâ€â€”until his first talkie, Blackmail (1929). Hitchcock’s very next feature, Downhill, is pure melodrama. It also stars Ivor Novello as a young man who takes the rap for his best friend, who is accused of impregnating a maid at their prestigious prep school. Novello is expelled, banished by his father from his upper-class parents’ home, and forced to live a life of “debauchery†as first an actor and then a gigolo. He must hit rock bottom before things can improve. Downhill, one of Hitchcock’s little-seen pictures, is welcome here, but it’s too long (as is the case with many of the filmmaker’s silent titles) and very histrionic.

Criterion’s 2K digital restoration of both films, however, is nothing short of miraculous. I had seen The Lodger many times, but I felt as if I was viewing it for the first time with the new Blu-ray presentation. The visual are sharp, clear, and visible—unlike the overly dark public domain versions you can find on YouTube and other DVD releases (MGM Home Video’s 2008 edition is an exception). A new score by Neil Brand, performed by the Orchestra of Saint Paul’s, is fabulous.

Supplements include the aforementioned piece on architecture; a new interview with film scholar William Rothman on Hitchcock’s visual signatures; excerpts from audio interviews between Hitchcock and François Truffaut, and Hitch and Peter Bogdanovich; an interview with Brand on composing the score; and the complete radio adaptation of The Lodger from 1940, directed by Hitchcock. The booklet contains essays on both films by critic Philip Kemp.

If you’re a Hitchcock fan, you owe it to yourself to pick up this excellent release of the movie that really started it all for the director. Hitchcock tried a few times during his Hollywood career to remake The Lodger as a sound picture, but it never happened (it has been remade a few times by others). One wonders if Hitchcock could have made his early effort better than it already is. It’s doubtful!

CLICK HERE TO ORDER FROM AMAZON