BY HANK REINEKE

Among devotees of horror and mystery-adventure films,

director Jesús “Jess†Franco remains a divisive character. His earliest, more traditionally constructed

films - say The Awful Dr. Orlof (1962)

and The Diabolical Dr. Z (1966) - are

usually held in some level of regard amongst traditionalists, while more

adventuresome moviegoers wax rhapsodic over his later perplexing, exploitative

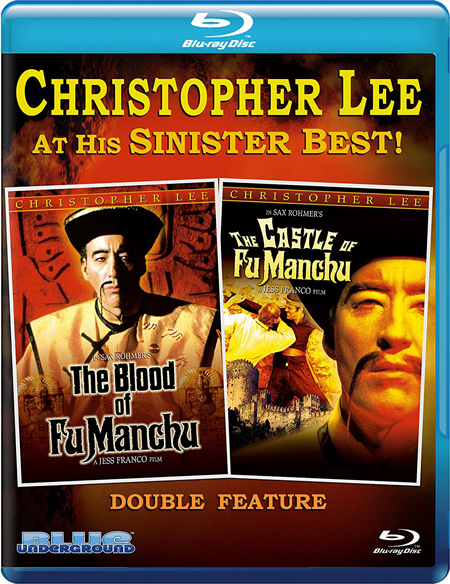

and occasionally pornographic art film exercises. Franco’s The

Blood of Fu Manchu (1968) and The

Castle of Fu Manchu (1969) are more conventional exemplars of traditional movie-making,

not as challenging to audiences as some of his more experimental post 1972

work. Both films are now available on a double-feature special edition Blu-ray

from Blue Underground.

The five Fu Manchu films produced by Harry Alan Towers from

1965 through 1970 are occasionally referenced – and perhaps dismissed - as weak

James Bond pastiches, but such description is misleading and unsatisfying. The Fu Manchu films as conceived by Towers and

Co. are akin to cinematic comic strips for adults – the two final strips admittedly

marketed to a more leering segment of mature audiences. Jess Franco was something of a

Johnny-Come-Lately to the series, perhaps a budget-minded choice of director. The first two films (The Face of Fu Manchu (1965) and The Brides of Fu Manchu (1966) were helmed by Australian Don Sharp,

the series’ third entry, The Vengeance of

Fu Manchu (1968) directed by Brit Jeremy Summers. For what would prove to be the final two

entries of the franchise, the producers went to the continent to seek out an

alternate director.

Jess Franco admitted to being surprised at having been

asked to direct the series’ fourth and fifth entries. In many respects the eccentric Spaniard was

worthy of Tower’s consideration as he shared the producer’s lifelong

enchantment with the comic-strip sensibilities of such popular dime store caliber-novelists

as Sax Rohmer and Edgar Wallace. But

while he manages to bring some sense of old world British Empire derring-do to

the screen, his two Fu Manchu films - with their attendant misfires and lurid

nude sequences – stand apart from the first three films in the series and remain

resolutely Franco in construction.

How so? Well, the

bevy of beautiful, half-naked women hanging sorrowfully in bondage chains is a

continually present and reoccurring Jess Franco fantasy. Christopher Lee’s co-star, Tsai Chin, recalls

the distinguished British actor’s discomfort parading in his Fu Manchu wardrobe

past a gaggle of chained, half-naked actresses. The epitome of gentlemanly British behavior, Lee was visibly distressed by

such staging. In Chin’s estimation,

while the cultured and mannered Lee was most determinedly a renaissance man, he

was certainly “not a womanizer.â€

Chin, the Chinese-born British actress then best known

internationally for her small role as agent “Ling†in the James Bond film You Only Live Twice, would have had some

insight in this matter. She returns in The Blood of Fu Manchu for her fourth outing

as Lin Tang, the sadistic, malevolent daughter of the mad villain. As in the series’ previous entries, Chin

portrays Tang as completely dispassionate, commanding her minions to torture

and humiliate innocents and enemies alike with merciless Oriental fervor.

In an interview with Tsai Chin years on and included here

as a bonus feature, the informed actress admits to having had to repeatedly

“search her conscience†to justify her participation in the Fu Manchu franchise. She was progressive enough to recognize that

the Sax Rohmer novels were unapologetically racist in their construction. Rohmer’s Fu Manchu series, the first novel having

been published in 1912, were written as blowback in the decade following the long

simmering anti-colonialist, anti-imperialist, anti-Christian, and decidedly anti-British

Boxer Rebellion of 1899-1901. But Chin was also keenly aware of racism in

the modern film industry; there were, simply, few opportunities for “ethnic†actors

to get work of anytime, so she soldiered on with the series despite her

misgivings.

In truth, the actress was sadly given very little

do. Chin believed, very accurately, that

the character of Lin Tang - as written by one “Peter Welbeck†- was completely

one dimensional. The actress was born a

year following MGM’s own esteemed Boris Karloff/Myrna Loy vehicle, The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932). In this pre-code film, the sultry Loy brashly

teased Lin Tang as a seductress and nymphomaniac. It’s extremely baffling why – in the swinging

sixties and with such nudity and bondage envelope-pushers as Franco and Towers steering

the enterprise – Chin’s Lin Tang was so wasted, cast as little more than a

remorseless, cruel bitch.

Christopher Lee wouldn’t suffer any moral quandaries as a

Caucasian playing an Asian villain with exaggerated epicanthic

folds – the responsibility of an actor, after all, is to effectively pretend

and make an audience believe that he or she is someone they are not. Regardless, the lanky Lee would admit

disappointment with the series as a whole. It was his opinion that, as had Hammer’s popular Dracula series, the Fu

Manchu franchise ran out of steam very quickly, that the earliest film had been

the finest and that the enterprise should have wrapped immediately following. It’s there, however, that the similarities

end. Lee’s exasperation with the

producing team at Hammer is well documented, but the actor - very interestingly

- seemed to carry little animus for Harry Alan Towers.

Lee partly explains his forgiveness of Towers’ increasingly disinteresting and exploitative films; he simply found the producer an ingratiating, mostly fair-minded and likable character. Towers’ would - more often than not - shoot his otherwise modestly budgeted films in exotic locations and Lee and his family were jetted, all expenses paid, to such locales as Hong Kong or Rio for the two or three weeks of his participation. In contrast, Lee was resentful that the producers of Hammer would literally “blackmail†him back into his Dracula cape by suggesting film crews and fellow actors would be out of work without his signing on.

However enamored he had become of the perks of working for Towers, Lee certainly wasn’t uncritical of the final product. Lee thought the screenplays of “Peter Welbeck,†an ill-disguised pseudonym for the producer, were completely banal and almost always inferior to Rohmer’s original stories. The actor couldn’t understand why Towers would license material from the Rohmer estate, only to throw out the better aspects of the novelist’s detective stories and replace them with inferior storylines.

In this regard Christopher Lee was in partial agreement with director Jess Franco. Franco thought Towers a brilliant writer but one who, perhaps, worked too fast for his own good. There was very little re-writing or thoughtful introspection and revisions made once a screenplay had been cranked out. Interestingly, Franco too was the target of similar criticisms. He shared with Towers a simpatico work style and the better part of his own post-1972 films were shot in great haste and sometimes assembled in an almost stream-of-consciousness manner.

It must be said that there’s no lack of on-screen talent on hand, almost all worthier than the material provided them. Actor Richard Green assumes, for the first time in the series, the role of Fu Manchu’s main adversary, Detective Nayland Smith. (Actors Nigel Green and Douglas Wilmer had previously played the role of Smith, who might best be described as a poor man’s Sherlock Holmes). Smith’s “Watson†is Dr. Petrie, played in each of the five films by British actor Howard Marion-Crawford. The one attribute the main antagonists and the chief protagonists have in common in both The Blood of Fu Manchu and The Castle of Fu Manchu is that neither really accumulates much screen time.

Speaking of little screen time, the British actress Shirley Eaton (Goldfinger) also appears as an unnamed leather-adorned “Black Widow†type character near the film’s end. It’s an odd sequence that seems to have been incomprehensively grafted into the film. Its inclusion seems to have no bearing on the existing plot, and neither Eaton nor Franco can explain its presence in the final cut. While Franco acknowledges neither reason nor memory for its inclusion, Eaton recognizes the sequence as having been excised from her spy film The Girl from Rio, yet another Harry Alan Towers production (and available on a 2004 DVD courtesy of Blue Underground). Though not released theatrically until 1970, The Girl from Rio was more or less shot concurrently in Brazil during the South American filming of The Blood of Fu Manchu. It’s likely that having Eaton’s name attached to the cast list of the Fu Manchu film made the already sagging franchise somewhat more appealing and marketable to investors and distributors alike.

The Blood of Fu Manchu begins with the nefarious villain in his Dr. No- like subterranean lair beneath an Incan ruin, addressing his “instruments of destiny.†Though chained and – rightfully - fearing for their lives, Fu Manchu informs the harem of half-naked girls that they were specially chosen to take part in his “great experiment.†Not one to let bygones be bygones, his great experiment is the murderous dispatch of his ten greatest enemies by a “kiss of death.†To accomplish this he has a poisonous snake on hand whose venom will somehow pass through girls and make their alluring, pouty kissable lips a conduit of death.

Once each girl is subjected to the bite of the reptile, she will be dispatched to the cities of far-flung enemies residing in London, Rome, Berlin, Tokyo, New York, etc. The comely woman will then seduce their unsuspecting prey by planting one on his kisser. The result of such titillating oscillation will be an immediate loss of vision and certain death – but only following a six week period of great suffering. That’s the gist of it anyway, though there are some plodding subplots concerning a greasy bandit by the name of Sancho Lopez (Ricardo Palacios) and a team of ill-fated archeologists in search of the “Lost City†led by buff Carl Jansen (Götz George). Along the way we’re treated to mariachi-accompaniment orgies in the village square, several unconvincing fight scenes, and a number of women parading about the screen in the sheerest of dresses and bust-line revealing peasant wear.

There’s both literal and metaphorical rough sailing ahead in the franchise’s sodden fifth and final entry The Castle of Fu Manchu (1969). Widely dismissed as the least engaging of the series, the film’s pre-credit sequence begins with Fu Manchu directing his minions (Burt Kwouk footage excised from The Brides of Fu Manchu) to activate his newest instrument of blackmail. This time he’s devised a high seas weapon capable of creating temporary icebergs even in the warm water climes of the Caribbean Sea. If the footage of a doomed ocean liner careening into Fu Manchu’s manufactured iceberg seems oddly familiar it’s likely due to the fact that we’ve seen it before. It would at least be familiar to those who’ve seen the 1958 British Titanic disaster film A Night to Remember. Since that film was originally shot in black and white, producers chose to give the footage a modest modern sheen by adding a blue tint to the cells.

There is, as always, a bit of a confusing sub-plot involving a kidnapped scientist and opium trafficking, and while the film is undeserving of the dismissive razzing it usually receives it’s inarguably the series’ dying gasp. Ostensibly photographed in Istanbul, the film was actually shot in Barcelona. Fu Manchu’s castle is the same one Franco would use for his film Count Dracula (1970), also starring Lee. The primary cast of the previous film is on hand here to lend semi-enthusiastic support, but the entire production feels a bit routine and uninspired.

In a fourteen minute supplement The Fall of Fu Manchu, actress Tsai Chin admits when the scripts arrived for The Blood of Fu Manchu and The Castle of Fu Manchu she didn’t even bother to give them a read over. The series had become so unimaginative and the characters so thinly drawn that she chose to simply take the money and run. Lee, having already acknowledged the series had irrevocably devolved, hasn’t much to do as Fu Manchu. He mostly barks out orders contrary to the wishes of the more cautious technicians who’ve engineered his newest weapon of mass destruction. Even producer Towers shared his feelings that The Castle of Fu Manchu was a flat-out misfire. He straightforwardly told Franco that the director had somehow accomplished what he thought otherwise impossible: “You’ve successfully killed Fu Manchu.†If Tower’s assessment is accurate, it can also be fairly said that Franco was but one of several accessories to that murder.

Blue Underground’s highly impressive all-region Blu-ray edition of The Blood of Fu Manchu and The Castle of Fu Manchu offers both films as 1080p HD resolution transfers in a 1:66:1 widescreen ratio and with English-language audio in mono DTS-HD. There are also a number of original supplements included, both ported over from Blue Underground’s 2003 DVD releases of these films. These include two short but illuminating documentaries “The Rise of Fu Manchu†and “The Fall of Fu Manchu†which feature interviews with director Jesús Franco and producer Harry Alan Towers, as well as cast members Christopher Lee, Tsai Chin and Shirley Eaton. The set also includes such supplements as theatrical trailers and a poster and still galleries.

CLICK HERE TO ORDER FROM AMAZON