BY NICHOLAS ANEZ

When No

Orchids for Miss Blandish premiered in London in 1948, it created controversy

that extended all the way to British Parliament. The Monthly Film Bulletin called the movie “the most sickening

exhibition of brutality, perversion and sex ever shown on a cinema screen.†The Saturday Pictorial called it “a

piece of nauseating muck.†The Observer’s

reviewer wrote: “This film has all the morals of an alley cat and the sweetness

of a sewer.†Some politicians were also offended. The Parliamentary Secretary

to the Ministry of Food said that the film “was likely to pervert the minds of

the British people.†Eventually, the British Board of Film Censors was

compelled to offer an apology for approving the film’s production.

Attempts to release the movie in the United

States by distributor Richard Gordon were met with threats by the New York

Censor Board as well as the Customs Department to confiscate it. Gordon had to

bring the movie into the country through New Orleans but it would still take three

years of bargaining and the removal of 12 minutes of objectionable scenes to

obtain approval for exhibition. Nevertheless, the edited version was still greeted

with harsh reviews. Time called it,

“ludicrous claptrap from a claptrap novel.†The

New York Times chastised it as “an awkward attempt on the part of the English

to imitate Hollywood’s gangster formula.â€

The critical disdain has never stopped. In

the multi-volume reference work, The

Motion Picture Guide, Jay Robert Nash and Stanley Ralph Ross

write “This a sick exercise in sadism (and) is about as wretched as they come.â€

The annual Halliwell’s Film Guide summarizes the movie as “hilariously

awful (and) one of the worst films ever made.â€

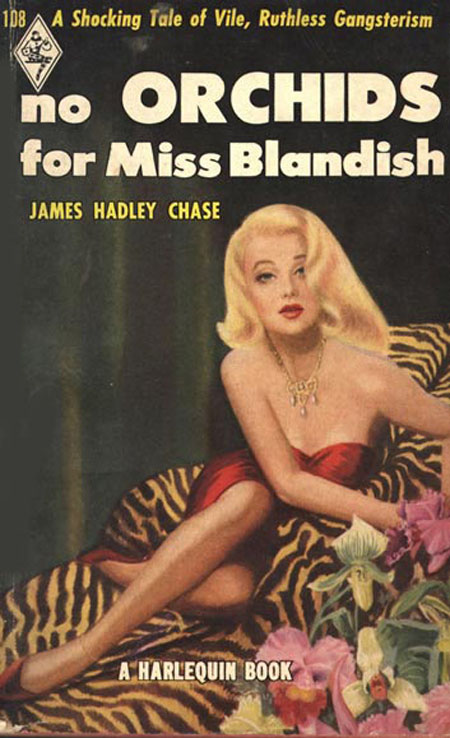

The movie is based upon the 1939 novel of the

same name by British author James Hadley Chase that was called everything from pulp

trash to borderline pornography. When it was published in America three years

later, it received equally terrible reviews with many critics accusing the

author of plagiarizing William Faulkner’s 1931 novel, Sanctuary. The novel concerns the daughter of a wealthy Kansas City

businessman who is kidnapped by the notorious Grisson gang, led my Ma Grisson

and her psychopathic son, Slim; she is subsequently subjected to repeated rapes

by Slim while in a drug-induced stupor. (Note: when Robert Aldrich directed his

film version in 1971, he changed the name from Grisson to Grissom for The Grissom Gang.)

After several attempts to film the novel were

aborted by the BFFC, producer George Minter signed playwright St. John Clowes

to write a script that eventually was approved. The script eliminated much of the

novel’s sleaze but, as it turned out, not enough. Clowes, who had directed one

previous film, also signed on to direct. Casting proved to be difficult because

of the novel’s notoriety. After several Hollywood actresses refused the role,

Minter signed British actress Linden Travers who had played Miss Blandish in

the London stage version which had been a huge success in 1942. (As in the

novel, Miss Blandish’s first name is never revealed.) For the role of Slim

Grisson, Minter hired Hollywood actor Jack La Rue whose most famous role had ironically

been as the gangster/rapist called Trigger in The Story of Temple Drake, the 1933 film version of Sanctuary. Due to that film’s infamy, La

Rue’s career had subsequently stalled and he had been reduced to playing bit

parts until he accepted the role of Slim Grisson.

Clowes changes the setting of the story from

1930s Kansas City to 1940s New York City and converts the sordid tale into a

love story. Slim Grisson is still a killer but is also a sensitive gangster who

has always had a torch for the heiress. Instead of being held prisoner and

sexually abused, Miss Blandish chooses to voluntarily stay with her captor and

become his lover. The other members of the Grisson gang remain murderous thugs who

become furious over Slim’s refusal to demand ransom from his paramour’s father;

this will lead to carnage within the gang. Mr. Blandish also undergoes some

changes from a cold patriarch to a caring father who longs for his daughter’s

return. Dave Fenner, the private detective of the novel, becomes a

wise-cracking reporter who discovers the culpability of the Grisson gang and

becomes their target. Meanwhile, the police are determined to end the gang’s

reign of terror. With all of these forces against their alliance, the lovers’

plan to escape to another country is doomed.

Regarding the controversy, the film contains numerous

scenes of depraved criminals committing acts of brutality along with periodic

scenes of suggestive sexual interludes among various characters. What particularly

shocked British gentry was the suggestion that an aristocratic woman would not

only voluntarily elect to have a sexual relationship with someone beneath her

social class but would actually enjoy it. This was simply unacceptable. Also, the

film’s depiction of a gang of killers with no redeeming qualities angered

social reformers who believed that lawbreakers were products of their

environment and could be rehabilitated if taken away from such milieu. Furthermore,

many British film critics disapproved of the popularity of Hollywood gangster

films and resented the idea of a home-based film emulating this despised genre.

Thus, the condemnation of the film was at least in part due to factors other

than the quality of the movie.

Director Clowes moves the film along at a

rapid pace and tells the story with an absence of artistic pretensions. Just as

Chase depicted a criminal world in which brutality and murder are standard

forms of behavior, Clowes depicts depravity as a normal way of life for his

characters. He moves his camera around efficiently, thereby enhancing the

effect of many scenes. He doesn’t exploit the savagery of the gangsters or

their innately primitive sexual desires. Though the violence was brutal for its

time, it isn’t graphic. For instance, when one of the gang members stomps Miss

Blandish’s beau to death, he keeps the camera on the hoodlum’s face. Indeed,

the climactic gun battle is not shown, thus emphasizing the film’s focus on the

romance. Clowes handles the sexual scenes with equal reticence. In one pivotal

scene, Slim unlocks the door and tells Miss Blandish to go home, not believing

that she genuinely loves him. As she leaves, he grimaces in anguish. Then the

camera focuses on orchids, accompanied by the sound of a door opening and

closing, signaling Miss Blandish’s return. The fadeout speaks volumes.

Linden Travers convincingly transforms Miss

Blandish from a superficially frigid heiress into a passionate lover and

finally into a totally devastated woman; Travers appeared in only four more

movies before retiring, except for some television appearances. Jack La Rue is

equally persuasive as a cold-blooded killer and as a romantic lover; nevertheless,

after this movie, he returned to cinematic obscurity. Hugh McDermott, who is

also billed above the title along with the two leads, makes Dave Fenner a

likeable protagonist. Though some of the supporting actors may have studied

Hollywood gangster movies for inspiration, they are all quite effective. And while

many U.S. critics mocked their American accents, all of the actors replicate

American accents as plausibly as Hollywood actors reproduce British accents in

innumerable movies.

In summary, No Orchids for Miss Blandish is not in the same class as such

acclaimed and contemporaneous British gangster movies as Brighton Rock and They Made

Me a Fugitive. But it shouldn’t be dismissed a failed imitation of

Hollywood crime thrillers, though it contains some recognizable motifs of the

genre including machine gun-wielding hoodlums and tough-talking molls. It is

also true that the occasional trite dialogue is reminiscent of 1930s B movies

while the sporadic melodramatic moments may also evoke earlier Hollywood

product. As a result, some current home video reviewers belittle the film. However,

Clowes and company set out to make a movie that, though taking advantage of its

sensationalistic origins, was salacious but not vulgar, titillating but not

obscene. They succeeded and created a movie that is entertaining and, at times,

even poignant. Furthermore, in the 21st century, the movie functions

as a cultural artifact that in the not-too-distant past unstiffened innumerable

stiff upper lips and thoroughly infuriated self-appointed moral guardians.

Note: The 2010 VCI Entertainment DVD release is

an excellent transfer of the movie and contains video interviews by Joel

Blumberg with distributor Richard Gordon and actor Richard Nielson, who plays

one of the Grisson gang hoods, as well as an audio interview with Mr. Gordon by

Tom Weaver. The disc also includes a photo gallery plus both the British and

American trailers. (Click here to order from Amazon)

The new (2018) Kino Lorber Blu-ray release

naturally has improved picture and audio quality; the movie looks like it was

made yesterday. But there are no extras other than the original trailers.

(Click here to order from Amazon)